A summary of Richard Joyce's 'The Evolution of Morality'

Metal.

To learn more about the evolution of cooperation from a philosopher’s perspective, I recently read Richard Joyce’s book The Evolution of Morality. Joyce’s book makes the case for the evolutionary debunking argument, which holds that moral beliefs are the product of evolutionary processes rather than tracking moral truths. While evolution has equipped us with the capacity for moral judgement, this doesn’t necessarily mean that our moral beliefs are true or justified. Instead, our moral sense evolved because it was useful for our ancestors’ survival and reproduction, regardless of whether moral facts actually exist.

Joyce begins by examining the evolutionary origins of helping behaviour, drawing on mechanisms familiar to evolutionary game theorists such as kin selection and mutualism. He proposes that emotions originally directed towards kin were co-opted for broader prosocial purposes. However, he argues this evolutionary account of helping behaviour falls well short of explaining morality in its full sense (Chapter 2). Even if humans had hypothetically evolved to behave in extremely altruistic ways, this alone would not constitute morality proper. The key distinction lies in the capacity for moral judgement. A creature could evolve with extreme inhibitions against behaviours we consider immoral, but without the concept of prohibitions and the ability to make moral judgements, it would not possess true morality.

This distinction leads Joyce to grapple with what moral judgement truly is. Some philosophers consider morality conative, suggesting statements like “Stealing is wrong” are akin to exclaiming “STEALING!!” in an angry voice, expressing disapproval rather than a factual claim. However, Joyce contends that moral judgements also involve cognitive beliefs. To support this argument, he employs Moore’s paradox sentences such as “Stealing is wrong, but I don’t believe it’s wrong”. The apparent contradiction arises because moral judgements also seem to express a cognitive belief. (His later discussion of moral projectivism also makes a compelling argument.)

A second distinctive property of moral judgements is their clout. Compare “I disapprove of fox hunting” to “Fox hunting is wrong”; the latter has much more ‘oomph’ than the former. When someone declares that fox hunting is wrong, they’re not merely expressing a personal preference, they’re making a claim that demands consideration from their audience regardless of the audience’s attitude towards the speaker or personal interests.

In Chapter 3, Joyce presents a contentious argument that non-human animals lack the capacity for moral judgement. He acknowledges that chimpanzees, for example, demonstrate complex social rules governing accepted and unaccepted behaviours (de Waal 1991). However, he argues these behaviours can be fully accounted for by aversions, inhibitions, and desires. He draws a distinction between these responses and the more sophisticated concept of acceptable and unacceptable behaviours, which involves evaluative concepts like transgression, prohibitions, and deserved punishment.

Joyce’s main argument for the absence of moral judgement in other animals hinges on the role of language, a stance he acknowledges is controversial among philosophers. He focuses on the concept of “thick evaluative terms” to illustrate his point. These are words like “kraut” that carry both a descriptive component (“German”) and an evaluative one (derogatory). Understanding such terms requires a “semantic ascent” — the ability to shift from discussing the subject to analysing the term itself — which requires metalinguistic knowledge. Joyce argues that while other animals might grasp descriptive concepts like “German”, they lack the linguistic capacity for evaluative concepts like “kraut”. This linguistic limitation prevents other animals from making true moral judgements. Consequently, what we might perceive as “punishment” among other animals is more accurately described as a “negative response”.

He acknowledges some readers might be unpersuaded by his argument, but a key question remains for us all: how does one move from having inhibitions to making judgements about prohibitions?

Joyce speculates that language may have evolved, in part, to facilitate the expression of evaluations, with gossip and indirect reciprocity playing pivotal roles. He argues that when we tell others about someone who cheated us, our goal isn’t to merely describe the event, but to criticise the action and potentially elicit a response from the listener.

Building on this, Joyce explores how many moral emotions are not only dependent on evaluative concepts but are also cognitively rich. He uses disgust as a prime example. While its biological root lies in food rejection, humans have elaborated this basic instinct into complex, almost superstitious beliefs. For example, people might refuse to wear a murderer’s jumper even after thorough laundering, revealing a concept of contamination that transcends physical reality. Joyce argues that while infants and non-human animals can experience distaste, they lack access to the full concept of disgust with its notions of invisible contaminants and realities distinct from appearance. Similarly, he examines guilt as another cognitively rich moral emotion. True guilt involves the concept that punishment is deserved rather than merely fearing or expecting it. While a dog might display guilt-like behaviour when acting submissively after wrongdoing, Joyce classifies this as proto-guilt, distinct from guilt proper.

In Chapter 4, Joyce examines the evolutionary benefits of self-directed moral judgement. He argues that moral conscience evolved as a more robust mechanism for scenarios where prudential judgement is too flexible and error-prone (e.g., “I should eat this salad for my future health”). Moral conscience says an action must be performed, silencing further deliberation, and it provides a strong motivation akin to how orgasm incentivises sex.

A key evolutionary advantage of moral judgement is its ability to unite self-directed and other-directed evaluations, serving as a ‘common currency’ for collective decision-making. Self-directed judgements act as a motivational bulwark, but they can also be publicly asserted, e.g., when staking a claim. The declaration ‘X is morally wrong’ demands avoidance from both the speaker and the audience. But because moralised thinking is motivationally resolute, it can also function as an interpersonal commitment. Emotions like indignant anger guarantee the pursuit of justice even at personal cost, which can be in one’s self-interest if it can be communicated to others.

Empirical evidence suggests that moral judgement is facilitated by emotions. Joyce argues for moral projectivism, drawing an analogy with colour perception. Just as we project the qualia of ‘red’ onto objects, we project emotions like pity onto situations, perceiving them as objective features (a pitiful situation) rather than subjective responses. This view can be contrasted with the traditional notion that moral judgements involve perceiving objective moral facts that exist independently in the world. While not definitively proven, moral projectivism aligns with our understanding of sensory perceptions and is consistent with two key features of morality: the precedence of emotions in moral judgement (as demonstrated in experiments manipulating disgust), and the perception that moral attributes exist objectively, which emerges in early childhood.

In contrast, Joyce finds it difficult to explain how moral judgements could be purely learnt. He questions how abstract concepts like ‘moral transgression’ could be taught through punishment alone, or how children could infer the distinction between moral and conventional rules without wide exposure to the full range of cases necessary to make the inference (e.g., an authority changing their mind about a moral transgression). Instead, he argues that, while the content of the moral judgement may be learnt, moral judgement itself is innate.

In Chapter 5, Joyce examines attempts to vindicate morality, beginning with the distinction between global naturalism and moral naturalism. He illustrates this difference using an analogy: one could ‘naturalise witchcraft’ by providing sociological and anthropological accounts without asserting the existence of witches. Similarly, one could offer a scientifically respectable account of morality without claiming moral beliefs are true. Moral naturalism, however, goes further to assert that moral properties and relations genuinely exist.

The naturalistic fallacy, while not applicable to global naturalism, is often considered a significant challenge to moral naturalism. However, Joyce notes that the common understanding of the “naturalistic fallacy” — deriving an “ought” from an “is” — differs from its original meaning. He clarifies G.E. Moore’s initial argument, which is that ‘good’ is indefinable due to its simplicity. Moore contended that ‘good’, akin to ‘yellow’, lacks constituent parts and therefore resists decompositional definition (unlike, say, “horseness” = quadruped + gramnivorous + …). This argument is distinct from the issue of deriving ‘ought’ from ‘is’.

Addressing the derivation of ‘ought’ from ‘is’, Joyce argues that moral naturalism doesn’t necessarily violate this principle. He draws a parallel with how tables and chairs can be understood within the framework of physics: moral naturalists could potentially demonstrate that moral properties are either identical to or supervene upon natural properties. While this task is challenging, Joyce suggests it shouldn’t be dismissed outright as impossible.

Joyce contends that evolutionary vindications of morality often falter for two primary reasons. First, many advocates propose an instrumentalist form of justification, which opens the door to the possibility that moral beliefs are merely “useful fictions”. This approach fails in Joyce’s view because he adheres to partial cognitivism, maintaining that moral beliefs are genuine beliefs. Second, those who offer epistemic justifications tend to employ non-normative definitions of “ought” (e.g., equating “ought” with “will happen”) that consequently fail to account for morality’s inherent clout.

Joyce then proceeds to examine several proposals in detail:

-

Richards (1986) argues that all justifications must eventually reach a stopping point, such as the modus ponens in logical arguments. He suggests that just as modus ponens derives its validity from the beliefs and practices of rational people, the transition from “is” to “ought” can be justified by examining the beliefs and practices of moral people.

Joyce counters this by suggesting it would be more logical to look to rational, rather than moral, people. He questions whether modus ponens is truly justified solely by appealing to rational judgement and points out that widespread assent doesn’t equate to an inference rule.

Richards also attempts to vindicate morality by proposing that evolution has adapted us to act for the community’s good, which he equates with morality.

Joyce, while accepting this premise for argument’s sake, contends through counter-examples that community good isn’t synonymous with morality (e.g., Genghis Khan’s henchmen acted for their community’s good). Moreover, he argues that even if one accepts this equivalence, evolutionary considerations at best suggest that humans will act to benefit the community, not that they ought to.

-

Campbell (1996) contends that morality is justified because it improves people’s lives.

Joyce critiques this, arguing that Campbell employs an incorrect notion of justification. He draws a parallel with religious belief: while it might improve lives, does that epistemically justify believing in gods? Joyce asserts that while this might provide instrumental justification, it falls short of the epistemic justification required for beliefs.

Campbell further argues that epistemic justification is inappropriate for morality, claiming that moral beliefs are distinctive not in their subject matter, but in being essentially dispositions to think, feel, and act in certain ways.

Joyce acknowledges that Campbell’s position is coherent, but only if morality is construed non-cognitively. He maintains that if moral beliefs are indeed beliefs, they must be subject to epistemic scrutiny.

-

Dennett (1995) posits that moral judgement plays a crucial practical role, and suggests that its efficacy might require avoiding excessive reflection on its functioning.

Joyce notes that the first part of Dennett’s argument is an instrumental justification, similar to Campbell’s position. Regarding the second point, Joyce interprets Dennett as potentially advocating a form of moral fictionalism, to which he is sympathetic. This view holds that while moral judgements may not be true, and we can acknowledge this, it remains beneficial to treat them as true in our daily lives.

-

Casebeer (2003) proposes a neo-Aristotelian account of virtue, where human purpose is understood in Darwinian terms. While evolution provides a framework to discuss the purposes of specific organs like hands or eyes, it doesn’t assign an obvious function to humans as a whole, so one might bridge this gap by using a concept like ‘organism flourishing’.

Joyce critiques this approach on several grounds. Firstly, he argues that a value system based on self-interest and harm avoidance doesn’t constitute a moral system in the traditional sense. He draws an analogy: we don’t praise a heart for pumping blood well, nor an assassin for excelling at their profession. Thus, evolution doesn’t provide a basis for moral ‘good’, even if such evaluations align with Aristotelian virtue ethics.

Furthermore, Joyce invokes Mackie’s observation about the ‘queerness’ of moral properties. If moral properties exist, they imbue situations with demands for certain actions, regardless of an individual’s personal aims, and these demands derive authority from no human source, existing merely to be perceived by moral agents. Joyce argues that Casebeer’s approach doesn’t resolve this metaphysical issue. Just as a heart’s function to pump blood doesn’t imply a demand that it must do so, identifying a function for humans wouldn’t inherently create a moral imperative to fulfil it.

In the final chapter, Joyce addresses the evolutionary debunking of morality. He begins with a thought experiment: if you discovered you had been given a pill that made you believe Napoleon lost at Waterloo, wouldn’t that make you doubt this belief? Joyce argues that the discovery that our moral beliefs are products of evolution should prompt a similar doubt.

One might counter that natural selection tends to produce true beliefs. For example, if the belief that 1+1=2 were innate and evolved, its evolutionary origin wouldn’t invalidate it because its selective advantage stems from its truth. The same argument could be applied to the faculties of scientific inquiry that underpin the evolutionary debunking of morality itself. However, drawing on Harman (1977, 1986), Joyce contends that this reasoning doesn’t hold for moral beliefs. We can understand how moral beliefs evolved and benefited our ancestors without those beliefs necessarily being true. While “right” and “wrong” might denote something real about the world, they might do so in a manner akin to terms like “ghost” or “witch”.

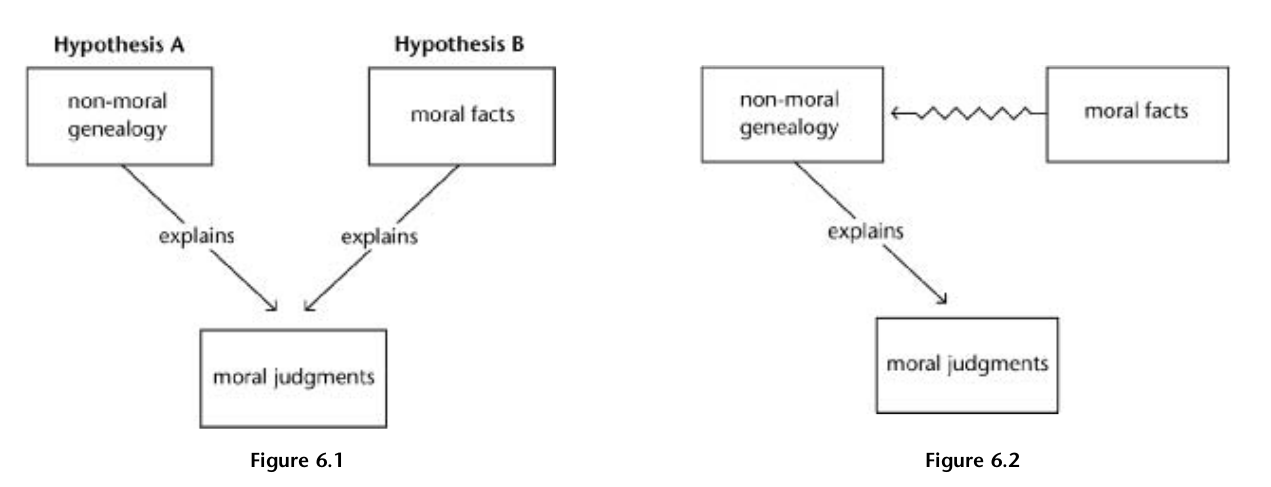

If a non-moral genealogy can fully explain moral judgement, the onus falls on moral naturalists to demonstrate why moral facts aren’t redundant (Fig. 6.1). This would require a reductive account that explains how moral facts relate to natural ones. Consider a hypothetical scenario: Jane sees children setting fire to a cat and judges it wrong. Can we explain Jane’s judgement without invoking the concepts of “cat”, “burning”, and “wrongness”? The concepts of “cat” and “burning” can be reduced to physics, so they’re implicitly present in that part of the causal explanation. However, if we can provide a naturalistic explanation for why the situation merely seemed wrong to Jane, we don’t need to posit the actual existence of wrongness to explain her judgement.

What constitutes an adequate reduction can be quite broad. While it’s challenging to move directly from physics and chemistry to concepts like “cat” and “burning”, we do have an account explaining how a burning cat is a physical and chemical entity. If a similar account can be provided for how moral facts are naturalistic entities, the critique would be satisfied (Fig. 6.2). However, to be credible, such an account would need to be as concrete and precise as a successful theory positing the existence of witches.

Figs. 6.1 and 6.2 contrast two situations for moral naturalism. In Fig. 6.1, the non-moral geneology explains moral judgements in an empirically verified way, which leaves the hypothesis of moral facts redundant. However, if moral facts can be reduced to the non-moral facts used in the non-moral geneology (wriggly line 6.2), then moral facts can’t be eliminated on the grounds of parsimony any more than cats are eliminated by physics and chemistry.

Joyce focuses on one key challenge facing moral naturalists: accounting for the inescapable practical authority that moral claims seem to possess. He chooses this example to illustrate a key point: if even a theory that equates moral facts with facts about reason can’t sufficiently explain this authority, what hope is there for theories that make this connection only indirectly?

The question becomes: how can naturalistic facts account for the clout of moral values? Essentially, we’re searching for a type of reason for action that can explain moral authority. Joyce examines two approaches:

-

Practical reasoning theory posits that an act is wrong if the agent has sufficient reasons not to do it. However, this theory falls short in explaining the inescapability of moral clout, which should have authority over people regardless of their personal interests.

-

The self-conception strategy argues that a rational person must treat morality as authoritative to maintain a coherent self-conception (e.g., a sense of integrity and identity). Yet this approach also has limitations. The reasons for action still depend on our actual desires, and the intangibility of the supposed self-harm caused by immoral actions is problematic. While some proponents describe the consequences of immoral actions in catastrophic terms (e.g., losing self-value), this seems disproportionate for minor transgressions like nicking a pen, which the theory must also account for.

Some philosophers argue that clout is not a necessary feature of morality. However, Joyce contends that without this authoritative element, morality would function more like etiquette– a set of contingent rules rather than absolute imperatives. Even steadfast desires, he argues, are insufficient to capture the essence of moral judgements. Joyce questions what the notion “X is morally wrong” adds to an account based solely on likes and dislikes. He had previously argued that moral discourse is necessary because it acts as a bulwark in ways that non-moralised practical deliberation cannot. However, this function is unavailable to proponents of moral naturalism who reject the notion of moral clout. Moreover, admitting moral discourse is superfluous would be inconsistent with moral realism, creating a dilemma for those who seek to maintain moral naturalism without the element of inescapable authority.

As an alternative to metaphysical theories, Joyce considers epistemic approaches that might vindicate moral beliefs regardless of their ontological status:

-

Process reliabilism holds that beliefs are justified when produced by processes that reliably link belief with truth, e.g., if natural selection favours organisms with at least approximately true innate beliefs. However, this approach faces two problems. First, the generality problem of specifying which is the relevant process (e.g., natural selection or specific cognitive mechanisms). Second, the deeper issue that natural selection may not always favour true beliefs, especially for intangible concepts like morality (cf., creation myths). The established existence of such beliefs also forces us to conclude that we’re faced with an unreliable process.

-

Epistemic conservatism holds that existing beliefs are rational unless proven otherwise. However, Sinnott-Armstrong (2006) identifies five attributes that can cast doubt on beliefs (a belief is partial, controversial, emotional, subject to illusion, and has unreliable/disreputable sources), including being explicable by unreliable sources, which applies to moral beliefs.

-

Epistemic coherentism suggests beliefs are justified by fitting coherently with other beliefs. However, when we include beliefs about the evolutionary origin of moral beliefs, which not only favour dropping a moral belief but also gives a scientifically respectable explanation for why the error occurred in the first place, then doubt is cast on the moral beliefs by coherentism’s own rules.

-

Moral intuitionism, a form of foundationalism, holds that some moral truths are self-evident. While this aligns with common intuitions about morality, items from Sinnott-Armstrong’s list (e.g., consider framing effects) again apply. More to the point would be to ask why moral beliefs seem beyond question and seem not to need further justification, to which the evolutionary geneology provides a good answer.

Thoughts

Joyce’s analysis has clarified for me a distinction in my research on the evolution of cooperation: while I’m seeking to explain cooperative behaviour, that falls short of addressing morality proper, which fundamentally involves judgement. The closest parallels are perhaps found in reputation models (indirect reciprocity), where rules emerge that align with our intuitions of “good” and “bad” behaviour (Ohtsuki and Iwasa 2004). However, even these models don’t fully capture the cognitive component and clout that Joyce identifies as essential to moral judgements.

Joyce’s emphasis on the role of clout suggests that before we can adequately model moral judgements, we need robust models of resolve and its failures. The concept of morality as an interpersonal commitment is particularly intriguing. It made me think of Sigmund et al.’s (2010) model of institutional punishment, though their model externalises commitment through pre-payment of taxes rather than internalising it. My own work on internal commitment in public goods games (in preparation, but similar to Newton’s (2017) threshold-PGG example) touches on related themes, but the commitment modelled there, being in the self-interest of collaborators, lacks the clout-bearing quality Joyce describes in true moral judgements.

I found it surprising that the primary challenges to moral naturalism centred on finding epistemic (rather than instrumental) justifications and employing a normative instead of descriptive version of “ought”. However, these challenges become more understandable in light of Joyce’s emphasis on cognitivism and clout. The concept of moral projectivism, with its clear analogy to qualia and sensory projection, struck me as particularly compelling.

References

Campbell, R., 1996. Can biology make ethics objective?. Biology and Philosophy, 11, pp.21-31.

Casebeer, W.D., 2003. Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition. MIT Press.

de Waal, F.B., 1991. The chimpanzee’s sense of social regularity and its relation to the human sense of justice. American Behavioral Scientist, 34(3), pp.335-349.

Dennett, D.C., 1995. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Simon and Schuster.

Harman, G., 1977. The Nature of Morality: An Introduction to Ethics. Oxford University Press.

Harman, G., 1986. Moral explanations of natural facts—Can moral claims be tested against moral reality?. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 24(S1), pp.57-68.

Joyce, R., 2006. The Evolution of Morality. MIT press.

Ohtsuki, H. and Iwasa, Y., 2004. How should we define goodness?—reputation dynamics in indirect reciprocity. Journal of theoretical biology, 231(1), pp.107-120.

Richards, R.J., 1986. A defense of evolutionary ethics. Biology and Philosophy, 1(3), pp.265-293.

Sigmund, K., De Silva, H., Traulsen, A. and Hauert, C., 2010. Social learning promotes institutions for governing the commons. Nature, 466(7308), pp.861-863.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W., 2006. Moral intuitionism meets empirical psychology. In Metaethics after Moore, ed. T. Horgan and M. Timmons. Oxford University Press.