Coherence-based reasoning and the downplaying of contrary evidence

Human reasoning often defies the ideal of normative inference, where conclusions should logically follow from evidence. Instead, we frequently engage in ‘backward reasoning’, starting with preferred conclusions and selectively seeking supporting evidence while discounting contradictory information. This tendency reflects a broader cognitive preference for beliefs that align with our existing worldview.

This inclination towards coherent beliefs contrasts sharply with foundationalist approaches to knowledge, which advocate building beliefs from self-evident truths (e.g., Descartes’ “I think; therefore, I am”). Our belief systems instead resemble intricate webs, characterised by complex interdependencies rather than clear hierarchies. Coherence-based reasoning is a cognitive model that attempts to capture these realities of human thought, where our beliefs are formed and held within this interconnected framework. This model not only describes how we form new beliefs but also how we maintain and adjust our existing belief systems in the face of new information.

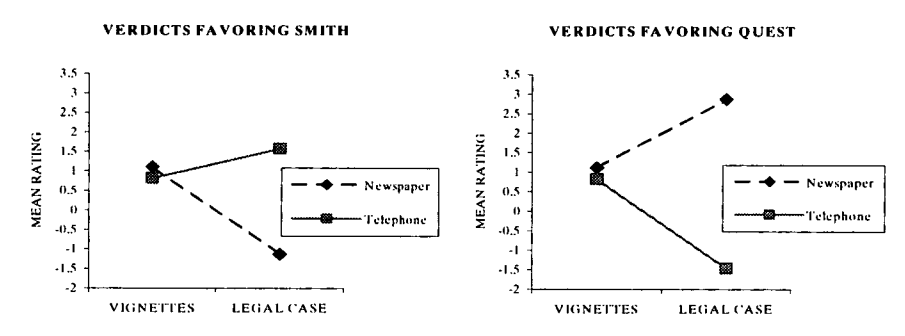

Experimental evidence supports the key hypotheses of coherence-based reasoning, showing that incipient conclusions can change how evidence is weighted. For example, in an experiment where participants were asked to judge a legal case, their evaluation of the evidence shifted to align with their eventual conclusions (e.g., Fig. 1). This ‘coherence shift’ phenomenon underscores the bidirectional nature of human reasoning processes.

Figure 1. Coherence shift in legal reasoning. Data from Simon (2004) shows how participants’ categorisation of the Internet (as more similar to a newspaper or a telephone) shifted to align with their verdict in a libel case. This categorisation was crucial for determining the applicability of libel law, demonstrating how conclusions can influence the interpretation of evidence.

Coherence-based reasoning, a Gestaltian cognitive-consistency model of human reasoning (reviewed in Simon and Read (2023)), is founded on the observation that we tend to accept propositions that align with our existing beliefs and reject those that contradict them. This theory, as formalised by Thagard (1989) in the ECHO (Explanatory Coherence by Harmony Optimisation) model, offers a compelling alternative to unidirectional theories of reasoning such as Bayesian inference. Proponents of coherence-based reasoning, like Simon et al. (2004), argue that the theory’s ability to capture ‘coherence shifts’ – such as those observed in the legal judgement experiment described earlier — makes it a more accurate representation of human cognitive processes (see also: Simon (2004); Glöckner and Betsch (2008)).

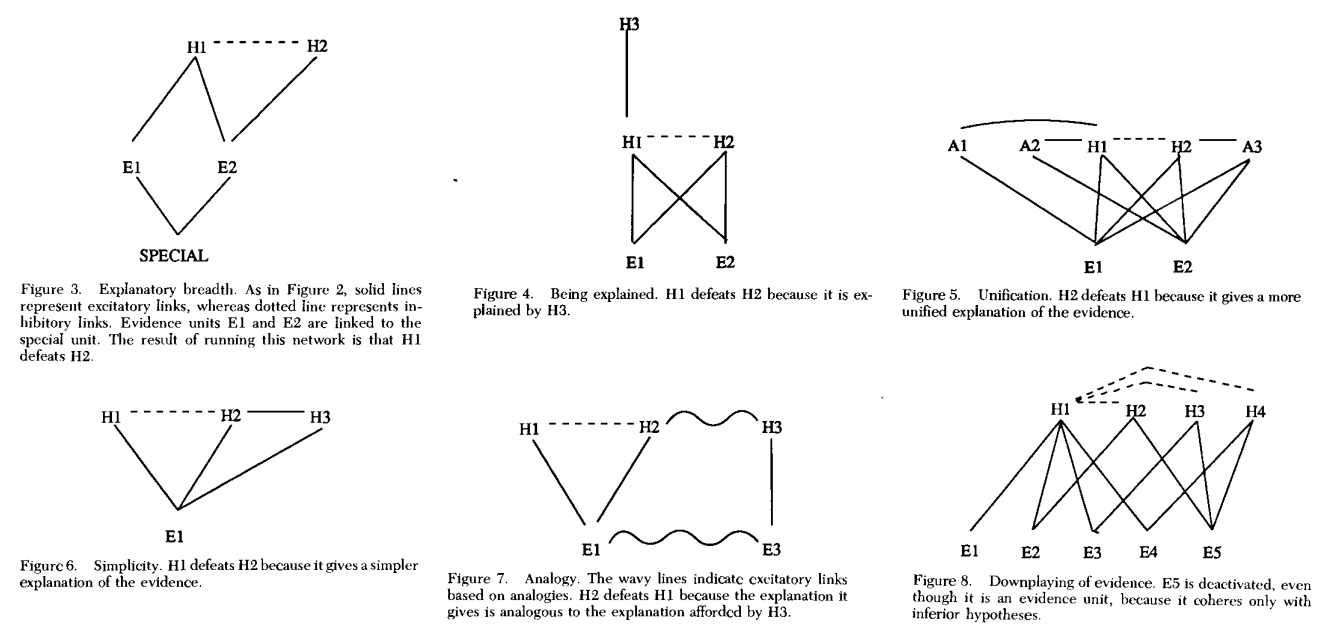

The ECHO model, proposed by Thagard (1989), formalises coherence-based reasoning using a connectionist framework. This model can be simulated using neural network techniques (e.g., Fig. 2) and consists of the following elements:

- Nodes: Represent individual pieces of evidence and hypotheses.

- Weighted edges: Signify relationships between nodes.

- Positive weights: Indicate explanatory links between hypotheses and evidence, co-hypotheses, or analogical connections.

- (b) Negative weights: Represent contradictions between hypotheses.

Figure 2. Examples of coherence networks from Thagard (1989), each illustrating a principle of explanatory coherence.

This network structure allows the model to simulate the complex interplay between different pieces of information and beliefs, mirroring the web-like nature of human cognition. By observing how activation spreads through a network, we can gain insights into how people might integrate new information, resolve contradictions, and ultimately form coherent belief systems.

Example

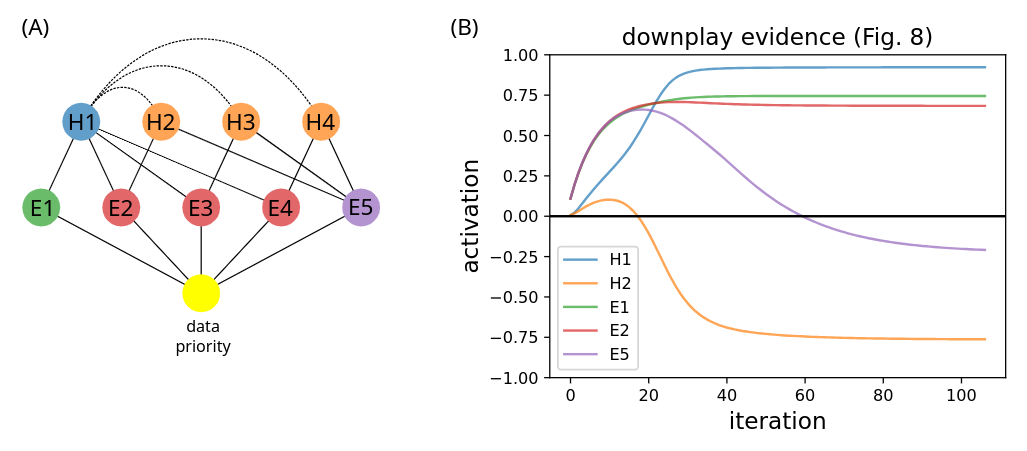

Consider the network structure illustrated in Fig. 3a, adapted from Fig. 8 of Thagard (1989). This network represents a scenario with five pieces of evidence (E1 to E5) and four hypotheses (H1 to H4). The relationships between these elements are as follows:

- Hypothesis H1 exclusively explains evidence E1 and also accounts for E2, E3, and E4.

- Evidence E5 is not explained by H1 but can be explained by hypotheses H2, H3, and H4.

- Hypotheses H2, H3, and H4 each explain only one additional piece of evidence besides E5.

- Hypotheses H2, H3, and H4 are mutually exclusive with H1, indicated by dashed lines.

- A ’special’ node represents data priority, connected to all evidence nodes.

Figure 3. Example from Fig. 8 of Thagard (1989): (a) network structure, and (b) activation of selected nodes over time.

To simulate this model, activation propagates from the data to the evidence nodes, which in turn activate their connected hypothesis nodes. The nodes then influence each other based on their positive (solid lines) or negative (dashed lines) relationships. This process continues until the system reaches a steady state, representing the final decision regarding the believability of the hypotheses and evidences.

The simulation requires setting initial weights for the links between nodes. Following Thagard (1989), I used the default weightings:

- \(w_{ij} = 0.05\) for excitatory links, and

- \(w_{ij} = -0.2\) for inhibitory links.

These weightings may by modified to penalise the complexity of an explanation and to adjust the weighting of analogical links (no analogical links in this example).

The model is simulated as follows.

- Initialise the `data priority’ node’s activation level \(a_0 = 1\) and all other nodes at some small initial value (default \(a_i = 0.001\)).

- For each timestep, update all nodes \(j > 0\) while keeping data-priority node constant at \(a_0 = 1\):

-

For each evidence and hypothesis node \(j\), calculate the net input to that node from all other nodes \(i\) connected to it

\[\text{net}_j = \sum_i w_{ij} a_i \label{E:net_j}\] -

For each evidence and hypothesis node \(j\), update the node’s activation level \(a_j\) according to

\[a_j(t+1) = a_j(t) (1 - \theta) + \begin{cases} \text{net}_j (\text{max} - a_j(t)) & \text{if } \text{net}_j > 0, \\ \text{net}_j (a_j(t) - \text{min}) & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \label{E:a_j_update}\]where max is the maximum node activation (default \(\text{max} = 1\)), min is the minimum node activation (default \(\text{min} = -1\)), and \(\theta\) is an activation decay parameter (default \(\theta = 0.05\)).

-

- Repeat Step 2 until the maximum absolute change in activation level of any node falls below a set tolerance (default \(\text{tol} = 0.001\)).

Fig. 3b illustrates how the activation levels of selected nodes in our example change over time. For example, the activation level of hypothesis H1 increases over time while all others H2-H4 decrease below zero. This represents the process of arriving at the conclusion that H1 is true and the other hypotheses false.

Notably, the example also illustrates the potential for evidence suppression. Although E5 is an established piece of evidence, its activation decreases over time. This occurs because E5 only supports the less favoured hypotheses H2-H4, which are ultimately rejected by the model.

Thagard (1989) explains the rationale between this counter-intuitive behaviour:

Principle 4 [of his 7 principles of explanatory coherence] asserts that data get priority by virtue of their independent coherence. But it should nevertheless be possible for a data unit to be deactivated. We see this both in the everyday practice of experimenters, in which it is often necessary to discard some the data because they are deemed unreliable (Hedges 1987), and in the history of science where evidence for a discarded theory sometimes falls into neglect (Lauden 1976).

Final thoughts

While we often view evidence suppression as a cognitive flaw, the model and example above suggests it may be an emergent property of an otherwise adaptive mechanism. Our ability to discount or deactivate certain pieces of information, like E5 in the example above, enables us to form coherent, actionable beliefs in a world of noisy, often contradictory data. This process isn’t about wilfully ignoring evidence, but rather about contextualising it within a broader explanatory framework.

While this coherence-seeking tendency can be advantageous in many real-world scenarios, it may also underlie problematic cognitive biases such as confirmation bias or belief perseverance. Understanding this dual nature of coherence-based reasoning — its adaptive value and potential pitfalls — offers a rather nuanced view of human cognition, and may lead to more sophisticated models of reasoning and decision-making.

References

Glöckner, A. and Betsch, T. (2008). Modeling option and strategy choices with connectionist networks: Towards an integrative model of automatic and deliberate decision making, Judgment and Decision making 3(3): 215–228.

Simon, D. (2004). A third view of the black box: Cognitive coherence in legal decision making, University of Chicago Law Review 71: 511.

Simon, D. and Read, S. J. (2023). Toward a general framework of biased reasoning: Coherence-based reasoning, Perspectives on Psychological Science p. 17456916231204579.

Simon, D., Snow, C. J. and Read, S. J. (2004). The redux of cognitive consistency theories: evidence judgments by constraint satisfaction, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86(6): 814.

Thagard, P. (1989). Explanatory coherence, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12(3): 435–467.