Guppy predator inspection

I read a very interesting new paper by Padget et al. (2023), published late last year in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The paper describes an experimental study of guppies’ predator-inspection behaviour, and it presents a bit of a mystery and a challenge to theoreticians.

Many fishes perform predator-inspection, which is when a small number of individuals will break away from the main group and approach a potential predator (Dugatkin, 1988). Performing the inspection is risky behaviour, but it also benefits the group; it can provide the information needed to either escape or return foraging if there’s no real threat (Padget et al., 2023). The ideal situation for any individual is for the inspection to take place but to not be one of the volunteers (but see Godin and Davis, 1995).

Male and female guppies. Contributed to the public good by Marrabbio2, Wikipedia CC.

This kind of situation is modelled by theorists using the Volunteers’ Dilemma (e.g., Archetti, 2009), which is a public goods game where the good is only produced if at least one group member volunteers to pay the cost. In the case of guppies, the ‘public good’ may be the information, and the cost is the risk of being eaten. This kind of game can be contrasted with the more familiar case of the (linear) public goods game, where the amount of public good increases linearly with the amount of cooperation. I’m particularly interested in this kind of model because, in contrast to the linear public good, nonlinear games like the Volunteers’ Dilemma have the possibility evolving and/or sustaining cooperation without assortment (Archetti et al., 2020) (though guppies might assort; see Darden et al. (2020)). Given that almost nothing is linear in biology, I think nonlinearity might have implications for how cooperation evolved (Kristensen et al., 2022).

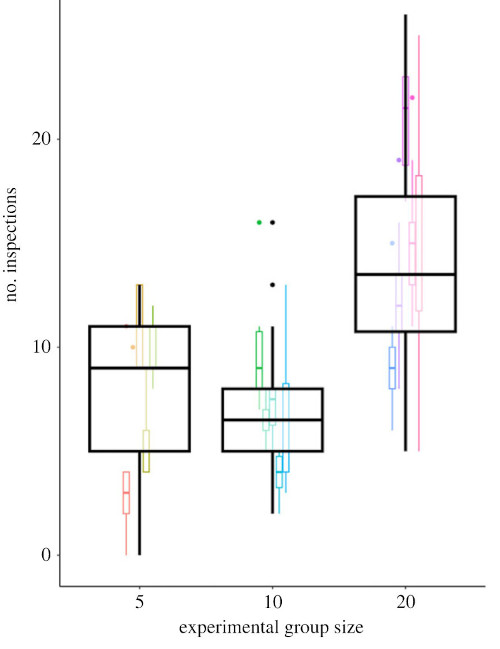

Volunteers’ Dilemma models predict that volunteering will decrease as the group size increase– but Padget et al. (2023) found the opposite. Comparing three group sizes, they observed that “Individuals in large groups inspected more frequently than those in both intermediate groups (moderate evidence) and small groups (weak evidence)” (Fig. 1). This suggests the models are missing something. They discussed a variety of ways the models could be made more realistic and whether or not such models could reproduce the observed behaviour (Supplement, my notes here), but the short of it was that the question remains open.

Figure 1a from Padget et al. (2023). The relationship between the experimental group size and the individual’s number of inspections.

As an exercise to learn more about mixed-strategy models, I created my own small model to explore. I focused on two aspects. First, the cost of volunteering to do the inspection is shared among the volunteers, so it should decrease as the number of volunteers increases. This sounds like it could potentially produce the desired positive relationship between volunteering and group size, but as Padget et al. (2023) point out, we already know that’s not the case. Weesie and Franzen (1998) investigated one such model, and they found that even if costs are shared between volunteers, volunteering will have a negative relationship with group size. Second, the cost of ignoring the potential predator is also likely shared among group members. This won’t produce the desired relationship, either, but I thought it would be a good exercise to combine the two.

Modelling exercise

The model

Consider two strategies: \(V\), volunteer; and \(I\), ignore the potential predator and don’t volunteer. Consider a focal individual \(0\) who pursues strategy \(s_0 \in \lbrace V, I \rbrace\) Let \(k\) denote the number of volunteers among the nonfocal members. Then the payoffs to the focal are

\[\begin{equation} w_0 = \begin{cases} 1 - \frac{c}{k+1} & \text{if } s_0 = V, \\ 1 - \frac{a}{N} & \text{if } s_0 = I \text{ and } k = 0, \\ 1 & \text{if } s_0 = I \text{ and } k \geq 1 \end{cases} \end{equation}\]Denote the probability of ignoring a potential predator by \(\gamma\). The expected payoff from ignoring is

\[\begin{equation*} W_I(\gamma) = \underbrace{\gamma^{N-1} (1 - (a/N))}_{k = 0} + \underbrace{1 - \gamma^{N-1}}_{k \geq 1} = 1 - \frac{a \gamma^{N-1}}{N}, \end{equation*}\]where \(N\) is the group size. The expected payoff from volunteering is

\[\begin{align*} W_V(\gamma) &= 1 - c \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} \left( \frac{1}{k+1} \right) \binom{n-1}{k} (1 - \gamma)^k \gamma^{n-1-k}, \\ &= 1 - \frac{c}{N(1-\gamma)} (1 - \gamma^N). \end{align*}\]Therefore, the payoff to an individual pursuing strategy \(\gamma'\) in a population pursuing strategy \(\gamma\) is

\[\begin{equation} W(\gamma'; \gamma) = \gamma' W_I(\gamma) + (1 - \gamma') W_V(\gamma) = W_V(\gamma) + \gamma' \underbrace{(W_I(\gamma) - W_V(\gamma))}_{g(\gamma)} \end{equation}\]Mixed-strategy equilibrium

Following, e.g., Bach et al. (2006), the mixed Nash equilibrium occurs when the payoff to the focal player is the same regardless of the strategy probability it pursues. This occurs when \(\gamma = \gamma^*\) satisfies

\[\begin{equation} g(\gamma) = W_I - W_V = \frac{c (1 - \gamma^N) - a (1 - \gamma) \gamma^{N-1}}{N (1 - \gamma)} = 0. \end{equation}\]We have

\[\begin{align*} g(\gamma = 0) &= \frac{c}{N}, \\ g(\gamma = 1) &= c - \frac{a}{N}, \end{align*}\]where the second equation makes use of \(1 - \gamma^N = (1 - \gamma) (\gamma^{N-1} + \gamma^{N-2} + \ldots + 1)\). Therefore, provided \(c < a/N\), \(g(\gamma)\) has at least one root between 0 and 1.

To characterise the root further, consider the numerator of \(g(\gamma)\)

\[\begin{equation} u(\gamma) = c (1 - \gamma^N) - a (1 - \gamma) \gamma^{N-1}. \end{equation}\]At the ends of the function, \(u(\gamma=0) = c\) and \(u(\gamma=1) = 0\). The derivative of the numerator

\[\begin{equation} u'(\gamma) = \gamma^{N-2} \left[ \gamma N (a - c) - a (N - 1) \right]. \end{equation}\]The derivative changes sign exactly once in the interval \(\gamma \in [0, 1)\), at

\[\begin{equation} \gamma_{\text{sign change}} = \frac{a(N-1)}{N(a-c)}. \end{equation}\]Furthermore, provided that \(c < a/N\) (which is the condition for the existence of at least one root, as above), then \(u'(\gamma = 1) > 0\). Therefore, \(g(\gamma)\) has a single root \(\gamma^*\), which is to the left of the sign change

\[\begin{equation} \gamma^* < \frac{a(N-1)}{N(a-c)}, \end{equation}\]and at that root

\[\begin{equation} g'(\gamma^*) < 0. \end{equation}\]Mixed-strategy equilibrium is an ESS

The strategy \(\gamma^*\) is an evolutionarily stable strategy (sensu Maynard Smith and Price) if, for small \(\varepsilon\)

\[\begin{equation*} \Delta W = W(\gamma^*; \varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) - W(\gamma; \varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) > 0 \end{equation*}\]is satisfied for all \(\gamma \neq \gamma^*\). We have

\[\begin{equation*} W(\gamma^*; \varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) = W_V(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) + \gamma^* g(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) \end{equation*}\]and

\[\begin{equation*} W(\gamma; \varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) = W_V(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) + \gamma g(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) \end{equation*}\]Therefore,

\[\begin{equation} \Delta W = (\gamma^* - \gamma) g(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) = (\gamma^* - \gamma) g(\gamma^* - \varepsilon(\gamma^* - \gamma)) \end{equation}\]We perform a Taylor expansion around \(\gamma^*\)

\[\begin{equation*} g(\varepsilon \gamma + (1 - \varepsilon) \gamma^*) = g(\gamma^*) - \varepsilon (\gamma^* - \gamma) g'(\gamma^*) + \mathcal{O}(\varepsilon^2) \end{equation*}\]So

\[\begin{equation} \Delta W = (\gamma^* - \gamma) g(\gamma^*) - \varepsilon (\gamma^* - \gamma)^2 g'(\gamma^*) + \mathcal{O}(\varepsilon^2) \end{equation}\]At the mixed Nash equilibrium, \(g(\gamma^*) = 0\); therefore, in order to satisfy \(\Delta W > 0\), we must satisfy \(g'(\gamma^*) < 0\), which we obtained above.

How the ESS changes with changes in costs and group size

We obtain the relationship between the ignoring probability at the ESS and the parameters and group size by implicitly differentiating \(u(\gamma^*)\).

The ignoring probability increases with cost of volunteering

\[\begin{equation*} \frac{d \gamma^*}{dc} = \frac{ (\gamma^*)^N - 1 }{ (\gamma^*)^{N-2} [\gamma^* N (a - c) - a (N - 1)] } > 0, \end{equation*}\]decreases with cost of being attacked

\[\begin{equation*} \frac{d \gamma^*}{da} = \frac{ \gamma^* (1 - \gamma) }{ \gamma^* N (a - c) - a (N - 1) } < 0, \end{equation*}\]and increases with group size

\[\begin{equation*} \frac{d \gamma^*}{d N} = \frac{ \gamma^* \ln(\gamma^*) [a (1 - \gamma^*) + c \gamma^*] }{ [\gamma^* N (a - c) - a (N - 1)] } > 0. \end{equation*}\]The final result, \(d \gamma^* / dN > 0\), agrees with the point Padget et al. made: sharing the costs does not change the direction of relationship between volunteering and group size predicted by models, which predict that volunteering decreases with group size.

Final thoughts

One thing that might be missing from these models is coordination. For example, when pairs of guppies perform the inspection, they do so in a tit-for-tat-like manner, each continuing their approach towards the potential predator provided that the other also continues their approach (Dugatkin, 1988; Dugatkin and Alfieri, 1991). This coordinative behaviour could be generalised to larger inspection parties.

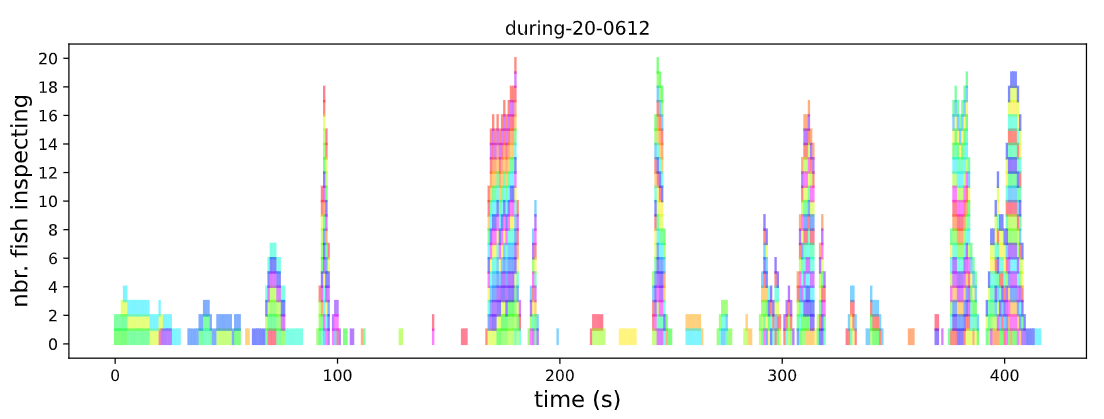

The number of fish ‘inspecting’ (within 30 cm of predator model) each second during one experimental trial. Each fish has been given a unique colour. Plotted from raw data provided with Padget et al. (2023)).

Reference

Archetti, M. (2009). Cooperation as a volunteer’s dilemma and the strategy of conflict in public goods games, Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22(11): 2192–2200.

Bach, L. A., Helvik, T. and Christiansen, F. B. (2006). The evolution of n-player cooperation—threshold games and ESS bifurcations, Journal of Theoretical Biology 238(2): 426–434.

Darden S. K., James R., Cave J. M., Brask J. B., Croft D. P. (2020). Trinidadian guppies use a social heuristic that can support cooperation among non-kin. Proc Biol Sci. 287(1934):20200487.

Dugatkin, L. A. (1988). Do guppies play tit for tat during predator inspection visits?, Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 23: 395–399.

Dugatkin, L. A. and Alfieri, M. (1991). Tit-for-tat in guppies (poecilia reticulata): the relative nature of cooperation and defection during predator inspection, Evolutionary Ecology 5(3): 300–309.

Godin J. J. and Davis S. A. (1995). Who dares, benefits: predator approach behaviour in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata) deters predator pursuit, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B.259193–200.

Kristensen, N. P., Ohtsuki, H. and Chisholm, R. A. (2022). Ancestral social environments plus nonlinear benefits can explain cooperation in human societies, Scientific Reports 12: 20252.

Padget, R. F., Fawcett, T. W. and Darden, S. K. (2023). Guppies in large groups cooperate more frequently in an experimental test of the group size paradox, Proceedings of the Royal Society B 290(2002): 20230790.

Weesie, J. and Franzen, A. (1998). Cost sharing in a volunteer’s dilemma, Journal of Conflict Resolution 42(5): 600–618.