Predator dilution effect synchronises fish migration

I recently came across a paper by Kaj Hulthen and others in Journal of Animal Ecology showing good empirical evidence for a model I coauthored a few years ago with Anna Harts and Hanna Kokko. Hulthen et al. (2022) were interested in the migration timing of roach (Rutilus rutilus). Specifically, they were interested in how the combination of selection for early arrival plus high predation risk could explain the relatively high migration synchrony in spring compared to autumn.

Roach migrate from lake to stream in autumn, and from stream to lake in spring. In the lake in spring, zooplankton numbers peak, and arriving too late may mean missing out on foraging and also mating opportunities. However, lake pike and piscivorous birds present a high predation risk. Individuals can reduce their predation risk by arriving later than the others, when there already many other roach in the lake. This provides ‘safety in numbers’, also known as the predator dilution effect.

A roach. By Karelj - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14954932 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Karelj.

According to our model (Harts et al. 2016), the net effect of selection for both early and late arrival (relative to conspecifics) is that selection will favour synchronous arrival– and this is also what Hulthen et al. found.

Hulthen et al. gathered highly detailed individual-based tracking data. They surveyed two different lake-and-stream systems, lake Krankesjön and lake Søgård, over 7 and 9 years, tracking 4093 and 1909 individuals, respectively. They used return migration as a proxy for survival, and measured synchrony in arrival time using Cagnacci et al. (2011, 2016)’s circular variable \(\rho\).

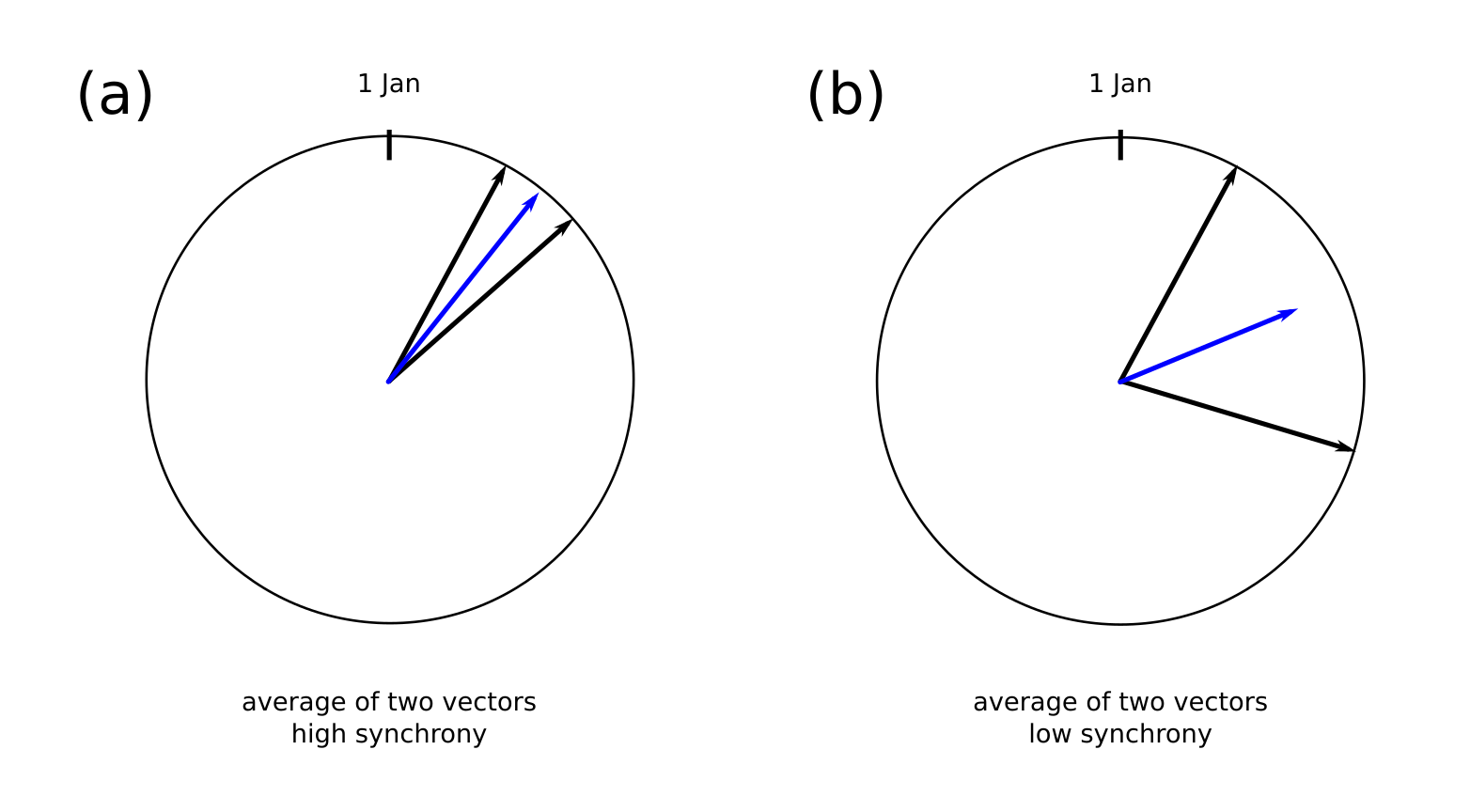

The circular variable is a rather neat way of summarising how synchronous timings are. The days of the year are evenly spaced along the perimeter of a circle with radius 1, and each arrival is encoded as a vector from the origin to the day. Synchrony is then measured as the length of the vector that results from taking the average of all the arrival vectors. The length varies from \(\rho = 0\) to 1, where low values indicate low synchrony and high values indicate high synchrony.

An example calculating the synchrony between two dates for (a) highly synchronous (b) less synchronous dates. The length of the average vector (blue) is the circular variable ( \rho ). The more synchronous the dates are, the longer the average vector is.

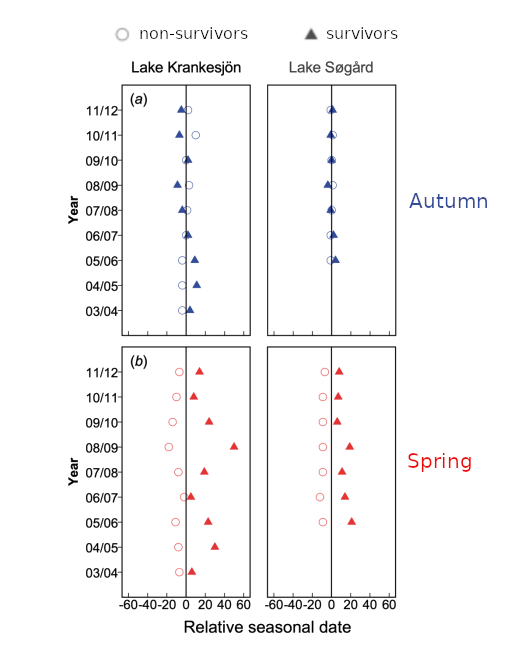

Hulthen et al. (2022)’s findings were that migration during spring, from streams to lakes, was more synchronous than migration during autumn. They also found that there was a survival cost associated with early migration in the spring but not the autumn, consistent with a predator dilution effect.

Comparing the relative migration timing of individuals who survived and did not survive to the next year. Non-survivors migrated earlier in the spring, but not in the autumn, consistent with a predator dilution effect that selects against arriving early relative to the bulk of the population in spring. Adapted from their Fig. 2.

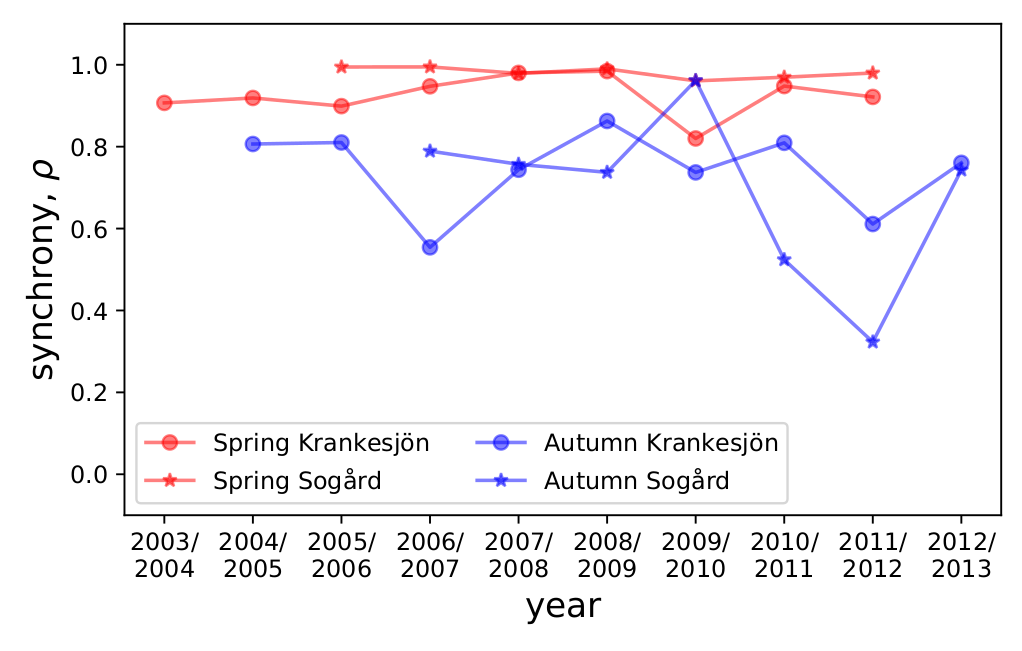

I was curious to see the synchrony result visually, so I downloaded their data and plotted the synchrony in each lake in each year for spring and autumn (Python script here). The effect is strong enough that it can be seen just by looking at this plot.

The synchrony ((\rho)) for each year for each lake in spring (red) versus autumn (blue). Synchrony is higher in spring than autumn.

It’s really interesting to me to see these results for fish. As Hulthen et al. note, a lot of the work on migratory timing is for birds, and certainly I had bird examples in mind when working on the model simply because that is my background. But evidently the concepts of early arrival and predator dilution are general and apply to many taxonomic groups.

Another recent study by Pärssinen et al. (2020) also found evidence of the predator dilution effect in fish. Hybrids of roach and bream had intermediate migration time that left them vulnerable to predation by cormorants. The special thing about predator dilution is that, all else being equal, the particular timing that evolves is evolutionarily stable but not convergent stable. Essentially this means that the timing that evolves is arbitrary, contingent on initial conditions or chance clustering. This implies there could be a great many timings that initiate or maintain divergence provided they are far enough apart and a large enough population maintains each timing.

References

Cagnacci, F., Focardi, S., Ghisla, A., van Moorter, B., Merrill, E. H., Gurarie, E., Heurich, M., Mysterud, A., Linnell, J., Panzacchi, M., May, R., Nygard, T., Rolandsen, C., & Hebblewhite, M. (2016). How many routes lead to migration? Comparison of methods to assess and characterize migratory movements. Journal of Animal Ecology, 85, 54–68.

Cagnacci, F., Focardi, S., Heurich, M., Stache, A., Hewison, A. J. M., Morellet, N., Kjellander, P., Linnell, J. D. C., Mysterud, A., Neteler, M., Delucchi, L., Ossi, F., & Urbano, F. (2011). Partial migration in roe deer: Migratory and resident tactics are end points of a behavioural gradient determined by ecological factors. Oikos, 120, 1790–1802.

Harts, A. M. F., Kristensen, N. P., & Kokko, H. (2016). Predation can select for later and more synchronous arrival times in migrating species. Oikos, 125, 1528–1538.

Hulthén, K., Chapman, B. B., Nilsson, P. A., Hansson, L. A., Skov, C., Brodersen, J., & Brönmark, C. (2022). Timing and synchrony of migration in a freshwater fish: Consequences for survival. Journal of Animal Ecology, In Press

Pärssinen, V., Hulthén, K., Brönmark, C., Skov, C., Brodersen, J., Baktoft, H., Chapman, B. B., Hansson, L-A. & Nilsson, P. A. (2020). Maladaptive migration behaviour in hybrids links to predator‐mediated ecological selection. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89(11), 2596–2604.