Little difference between real food webs and randomly assembled webs

What determines the structure of a food web? It has long been theorised that food-web assembly is a selective process, allowing only certain species and interactions to persist in the face of dynamical stability constraints. In Leo Saravia’s recent paper in Journal of Animal Ecology, we used a novel test to see if we could detect the signal of this selection. We compared the structure of real food webs to those of webs randomly assembled from the regional metaweb. Contrary to theoretical expectations, we found almost no difference between them.

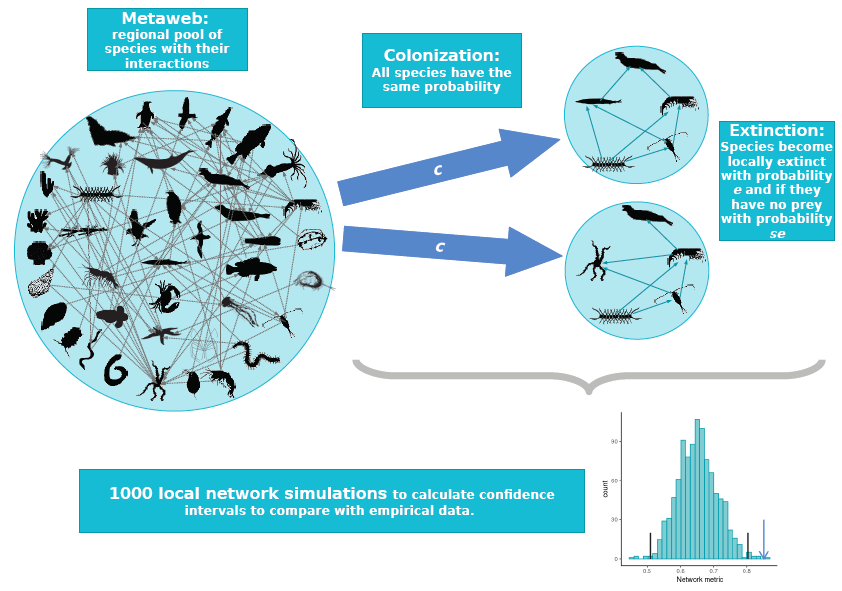

Figure 1: The null food-web assembly model. Species randomly colonise from the metaweb and go extinct in the local web, with the only constraint being that predators cannot persist unless they have at least one prey. We simulated 1000 local networks, and compared the distribution of their network properties to the properties of real webs.

Local food webs result from a repeated process of arrival, colonisation, and extinction by species from the regional pool or metaweb. That implies that food web structure is determined by two broad factors:

- the composition of the metaweb, which provides an ultimate constraint on which species and interactions are possible; and

- a complex combination of local selective processes, which constrains which species and interactions can persist locally.

Real food web structure should reflect both these factors.

The food-web assembly process is theorised to be a selective process. Which regional species can arrive and persist in a web is influenced by dispersal, environmental filters, biotic interactions, etc. Of particular interest is the effect of dynamical constraints. Some theorists hypothesise that the species combinations and network substructures that destabilise a web will be quickly lost, leading to an over-representation of stabilising structures in real food webs.

Food webs do tend to have properties that promote stability. For example, they tend to have a skewed distribution of interaction strengths and a high frequency of stabilising 3-node sub-networks (motifs). However, these properties can arise also for other reasons. Furthermore, without an appropriate baseline for comparison, it is unclear whether their observed frequency is unusual or unexpected.

The goal of this study was to test for evidence of these selective processes by comparing the structural properties of real food webs to the expected distribution given the metaweb. We used the novel approach of randomly assembling model webs by drawing species and interactions from the empirical metaweb (null assembly model, Fig. 1). The assembly model permitted colonisation and extinction, required a consumer to have at least one prey, but it had no habitat nor population dynamic constraints.

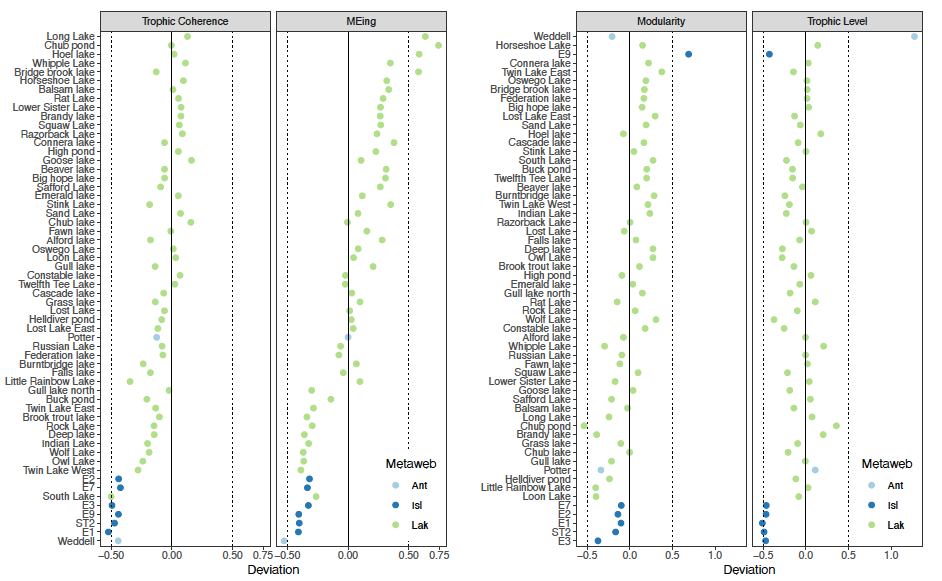

Contrary to our expectations, we found that there were almost no differences between empirical webs and those resulting from the null assembly model. Few empirical food webs showed significant differences in their network properties, motif representations or topological roles. Furthermore, real webs did not display any consistent tendency to deviate from expectation in the direction predicted by theory, particularly when the lakes dataset was included. For example, Weddell Sea seems to have unusually high stability, but the result looks less unusual when the whole dataset is compared (MEing, Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Comparing structural metrics between real and randomly assembled food webs: trophic coherence, mean maximum eigenvalue, modularity, and mean trophic level. Most structural properties did not differ significantly, and – contrary to theoretical expectations – real webs did not display a consistent tendency to deviate in the direction that promotes dynamical stability.

Our results suggest that local food web structure is not strongly influenced by dynamical nor habitat restrictions. The structure is inherited from the metaweb. This also suggests that the network properties typically attributed to stability constraints may instead be a by-product of assembly from the metaweb.

We caution that the metrics commonly used to summarise food-web structure, including those associated with stabilising structure, may be too coarse to detect the true signal of local processes. For example, generalisations about the relationship between modularity and stability cannot be made without first characterising the distribution of interaction strengths.

In conclusion, for the metrics we considered, food webs are mainly shaped by metaweb structure, and we did not find good evidence for the influence of local dynamics. This kind of analysis needs to be expanded to other regions and habitat types to determine whether it is a general finding.