Island bird diversity not influenced by historical connection to the mainland

The number of species on an island generally increases with island size and connectance to the mainland. However, if an island’s characteristics have changed in the recent past, that pattern will be disrupted. In Keita Sin’s recent paper in Journal of Biogeography, we tested if that expectation was borne out for birds on the Sundaic islands. Perhaps surprisingly, we found that it was not.

The number of species on an island is generally determined by immigration and extinction (MacArthur & Wilson, 1967). Over long timescales, these two forces reach a stochastic equilibrium, producing the well-known species-richness patterns. Larger islands permit larger populations that are less likely to go extinct, and proximity to the mainland and connectance to it (e.g., via stepping-stone islands) increase the chance of colonisation by new species. As a consequence, larger islands and islands with greater connectance to the mainland have higher species richness.

However, these general species-richness relationships assume static conditions. If an island has recently decreased in size or connectance to the mainland, then we would expect it to have more species than similar islands that have not changed (see previous blog post). This is because it takes time for species diversity to decline to reach its new, lower stochastic-equilibrium value. The mechanism is similar to extinction debt, where there is a time delay between habitat fragmentation and species extinction.

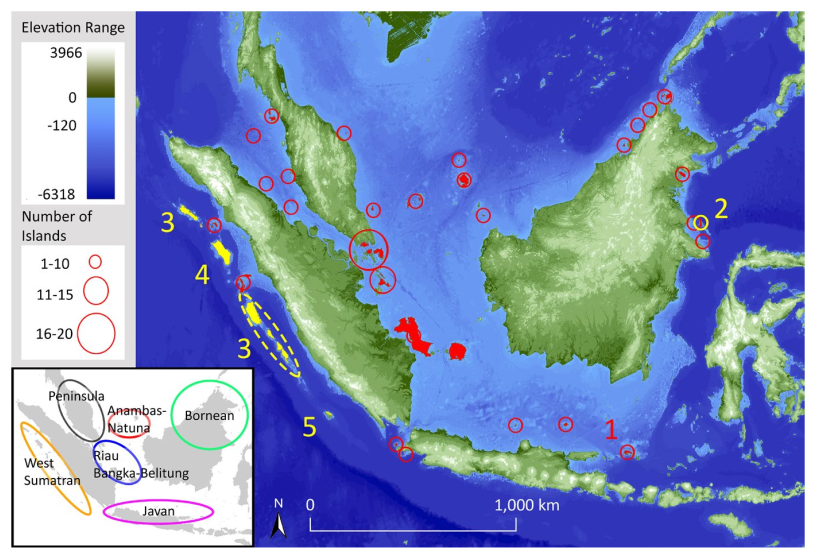

Over the past 20,000 years, sea level changes have changed the size and connectance of Sundaic islands. During the Last Glacial Maximum, the sea level was about 120 m below its present level, and the Sunda shelf was exposed and formed a large continuous landmass with Asia. More recently, around 7000 years ago, there was a peak 3-5 m above the current level, and low-lying islands were completely submerged.

The particular ways in which each island changed depends on the specific topology of the shelf around that island. As a consequence, two islands of similar size and connectance today can have very different histories of size and connection to the mainland, providing a natural laboratory for macroecological theory.

Figure 1: A map of the study islands. Note the Sunda shelf in light blue. At the Last Glacial Maximum (20,000 years ago), the Sunda shelf was above sea level.

Previous work has found that historical changes to island characteristics can influence species richness today. For example, in Baja California, the diversity of lizards was higher than expected in islands that were more recently connected to the mainland (Wilcox, 1978). Similar results have also been found for certain birds on satellite islands of New Guinea (Diamond, 1972). However, some studies have found little effect (e.g., Sundaic mammals, Heaney (1984)).

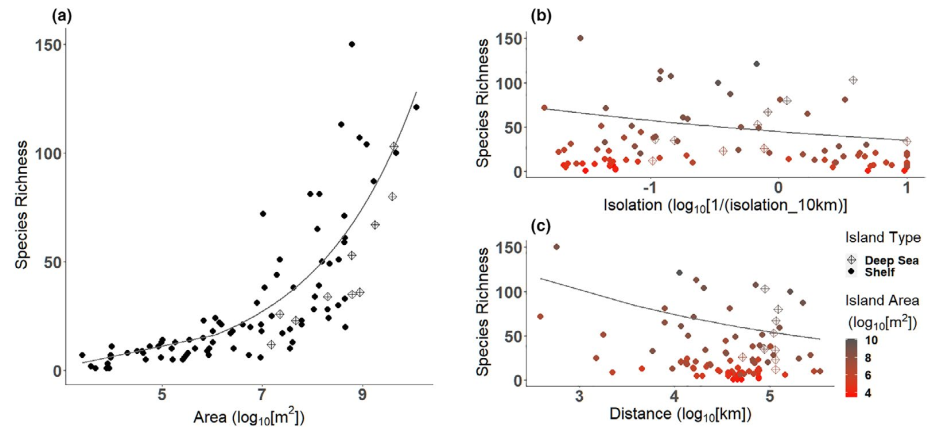

We found that an island’s historical characteristics had little effect on species richness. Two islands of similar size had similar diversity regardless of how long they had been disconnected from the mainland, or whether they had been recently submerged or not. This implies that, for Sundaic birds, the stochastic immigration-extinction equilibrium is reached relatively rapidly. Extinctions occur soon after an island becomes disconnected from the mainland, and highly dispersive species rapidly colonise islands that had been recently submerged.

Figure 2: The relationship between island species richness and (a) island area, (b) isolation in a 10 km buffer, and (c) distance to the mainland. The best model (by AIC) to explain species richness on islands included these 3 variables. It did not include change in the island’s area, time of isolation from the mainland, whether it had been submerged, or whether it was a deep-sea versus shelf island.

The one effect of island history was on island endemism: most island endemics were found on deep-sea islands with no historic land connection to the mainland. This was true even though some shelf islands are currently more isolated today than the deep-sea islands in the dataset. This implies that, although birds are a relatively dispersive taxonomic group, long-distance overwater colonisation is generally unsuccessful in the less dispersive species.

A special note needs to be made about the uniqueness of the dataset collected by Keita and the team. Although ornithological knowledge of the region is fairly comprehensive, the overwhelming majority of surveys have concentrated on large islands, creating a serious bias in the literature. In contrast, the surveys conducted for this study focused on small islands (less than 10 sq-km), providing valuable data to test theory across the range of mechanisms that determine island species diversity.

References

Diamond, J. M. (1972). Biogeographic kinetics: Estimation of relaxation times for avifaunas of southwest Pacific islands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 69(11), 3199–3203

Heaney, L. R. (1984). Mammalian species richness on islands on the Sunda Shelf, Southeast Asia. Oecologia, 61(1), 11–17

MacArthur, R. H., & Wilson, E. O. (1967). The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press.

Wilcox, B. A. (1978). Supersaturated island faunas: A species-age relationship for lizards on post-Pleistocene land-bridge islands. Science, 199(4332), 996–998