Sequential sampling schemes (urn models) for neutral ecological models

A random sample of a species abundance distribution from a neutral metacommunity can be generated using a sequential sampling scheme or urn model (Etienne, 2005, 2007). An urn model is an idealised systems where some objects of actual statistical interest are represented as colored balls in an urn. In the ecological context, the balls represent individuals, the different colours are different species, and the urn’s final state represents the sample.

I posted previously about the sequential sampling scheme that is used to generate a random sample from a neutral metacommunity. Hubbell (2001) called it a ‘species generator’, but the concept originated in the genetics literature. The connection to the genetics literature is because the random ecological drift in Hubbell’s neutral model is directly analogous to random genetic drift in a genetic model.

A neutral model can be sampled using a sequential sampling scheme because the neutral model is equivalent to a coalescence model (Rosindell et al., 2008) and a coalesence model equivalent to a sequential sampling scheme (Branson, 1991).

The coalescence approach to the neutral model involves tracing the lineages of individuals back in time until the species identity of every individual is known (Etienne and Olff, 2004; Rosindell et al., 2008). At each step, a lineage may either coalesce with another lineage or terminate with a common ancestor who is a new species. Coalescence means the species identities of all individuals in both lineages are the same, and the species identity of the common ancestor is either the result of speciation or, in the island models below, immigration from the mainland. A coalescence model is equivalent to a sequential sampling scheme for reasons explained in the genetics literature (reviewed in Donnelly, 1986).

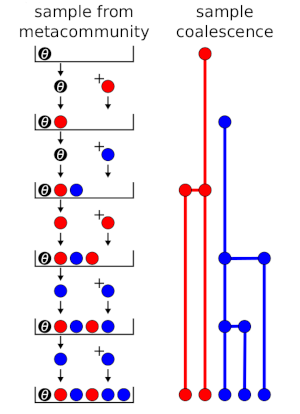

Each event in the coalesence tree, either a coalescence of two lineages in a common ancestor or a point-speciation, corresponds to a draw from the sequential sampling scheme. To generate a random sample of individuals from the metacommunity, the \(j\)th individual drawn is labelled as a new species (different from the \(j-1\) previously sampled) with probability

\[P(j \text{ is a new species}) = \frac{\theta}{\theta + j-1}\]or labelled as a member of a previously sampled species \(s\) with probability

\[P(j \text{ is species } s) = \frac{n_s}{\theta + j-1}.\]where \(\theta\) is the fundamental biodiversity number (Hubbell, 2001), and \(n_s\) is the number of individuals of species \(s\) already in the sample.

Fig. 1 shows the process as an urn model and compares it to the coalesence tree. tree. A black ball with weight \(\theta\) (fundamental biodiversity number) is placed into the urn. At each step, a ball is drawn and returned, and a new ball is added, depending on the colour of the ball drawn. If a coloured ball is drawn, then a ball of the same colour is added (coloured balls have weight = 1), corresponding to branching in the coalescence tree. If the black ball is drawn, then a ball of a new colour is added, corresponding to speciation. In Fig. 1, there are 2 red balls and 3 blue balls at the end, which represents a sample with 2 individuals of one species and 3 individuals of another.

Figure 1: Urn model and coalescence outcomes for random sampling from a metacommunity.

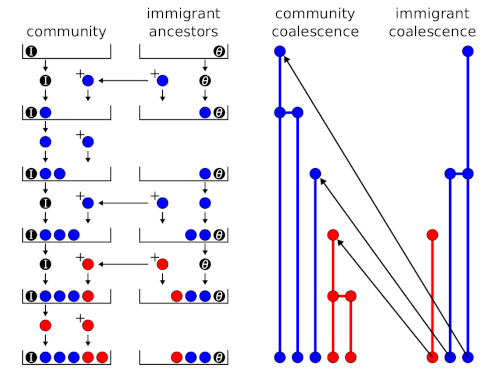

To model an island community, a sequential sampling scheme involving two urns can be used (Etienne 2005). New species arrive on the island by immigration instead of speciation, which is governed by an immigration rate parameter

\[I = \frac{m (J-1)}{1-m}\]The immigration parameter \(I\) playes the same role as \(\theta\) previously. Assuming that immigrants are a random sample from the mainland, their species identities are determined using the seqential sampling scheme for a random sample from the metacommunity above (i.e., Fig. 1).

Fig. 2 shows the urn model for an island community. A black ball with weight \(I\) (immigration parameter) is placed into the ‘community’ urn, and a black ball with weight \(\theta\) is placed into the ‘immigrant ancestors’ urn. At each step, the ‘community’ urn is sampled first. If a coloured ball is drawn, a ball of the same colour is added to the ‘community’ urn only. If the black ball is drawn, a draw from the ‘immigrant ancestors’ urn determines the colour of the new ball, which is added to both urns. A coloured ball adds the same colour to both urns, the black ball adds a new colour to both urns.

Figure 2: Urn model and coalescence outcomes for a single community (e.g., an island).

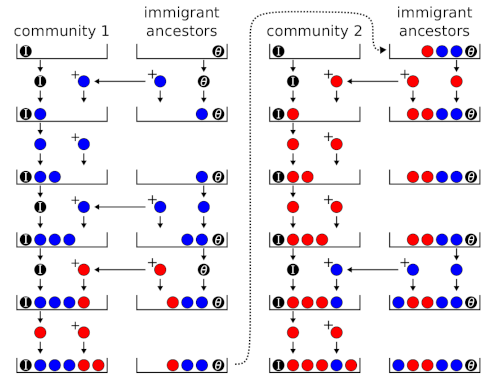

To model multiple islands, we assume that they are connected by immigration to the same mainland but not to each other. Therefore, there is one urn for each island and an immigrant ancestors urn is shared between them (Etienne 2007). Note that, although the sequence of draws corresponds to a temporal sequence of events in the coalescence tree, for a given final outcome, the probability of every temporal sequence is the same. Therefore, Etienne (2007) was able to simplify the scheme by sampling the islands sequentially without altering the probability distribution of outcomes.

Fig. 3 shows the urn model for a collection of communities sharing the same metacommunity. There is a single ‘immigrant ancestors’ urn and a a separate ‘community’ urn for each local community. ‘Community’ urns are filled sequentially according to the same rules as Fig. 2.

Figure 3: Urn model for 2 communities (e.g., islands in an archipelago).

References

Branson, D. (1991). An urn model and the coalescent in neutral infinite-alleles genetic processes, Lecture Notes-Monograph Series pp. 174–192.

Donnelly, P. (1986). Partition structures, Polya urns, the Ewens sampling formula, and the ages of alleles, Theoretical Population Biology 30(2): 271–288.

Etienne, R. S. (2005). A new sampling formula for neutral biodiversity, Ecology Letters 8(3): 253–260.

Etienne, R. S. (2007). A neutral sampling formula for multiple samples and an ‘exact’ test of neutrality, Ecology Letters 10(7): 608–618.

Etienne, R. S. and Olff, H. (2004). A novel genealogical approach to neutral biodiversity theory, Ecology Letters 7(3): 170–175.

Hubbell, S. P. (2001). The unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography, Vol. 32, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA.

Rosindell, J., Wong, Y. and Etienne, R. S. (2008). A coalescence approach to spatial neutral ecology, Ecological Informatics 3(3): 259–271.