Boolean approach to qualitative network modelling

In a new paper in Methods in Ecology and Evolution (draft with supplementary here), we tackled an important question for ecological modellers: how do we predict an ecosystem’s behaviour when the data needed to parameterise a model are lacking? This problem is particularly important when our models are needed for conservation decision-making. For example, managers may be considering different pest-control programmes, which have the potential to lead to negative outcomes for native species, and predictions of these outcomes are needed for sound decisions to be made. These outcomes can in principle be predicted using dynamical models, however experts rarely have data needed (i.e. quantifying every species’ interaction strengths) to parameterise the model. Is there a way to obtain predictions of species responses from the model anyway?

Recently, a suite of techniques known as Qualitative Modelling have become popular because they hold the promise of overcoming common data limitations. They do this by analysing ensembles of possible ecosystem models to provide probabilistic predictions. For example, probabilities of positive and negative species responses from a pest control model can be obtained using Monte Carlo simulations, by sampling unknown interaction-strength values from a uniform prior. However, we showed that these techniques are not robust to equally defensible variations in the sampling method used, leading to the paradoxical result that quite different probabilities can be obtained for the same predicted outcome. Worse, the degree of difference can be large enough to change the management decision that would result.

We turned to the philosophy literature to understand the root cause of these contradictory predictions. Similar paradoxical results are described by philosophers, arising in simple thought-experiments involving the Principle of Indifference (e.g. Bertrand’s paradox). The paradoxes occur when there isn’t sufficient background information about the problem to specify the parameter space. While the intuition behind Qualitative Modelling is philosophically sound - that unknown parameter values should be favoured equally - paradoxes arise when this equal favouring is represented by a probability distribution like a uniform prior.

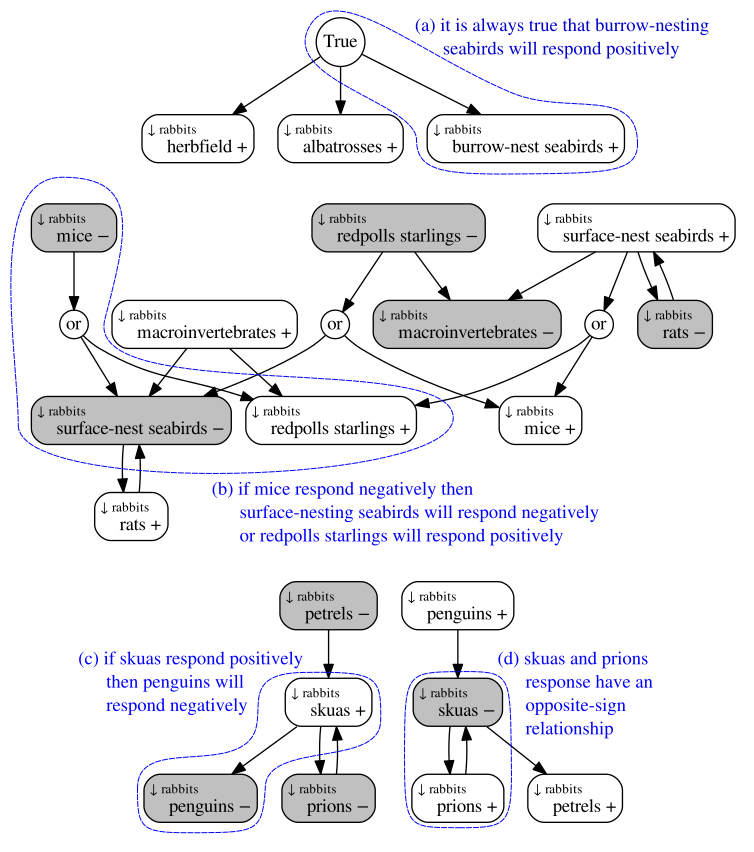

To resolve the problem, we adopt a non-probabilistic representation of parameter-value uncertainty: every possible value of an unknown parameter is simply classified as ‘possible’. At first glance, this does not seem like it would be very useful. However, we know that in dynamical models, the network structure of an ecosystem (e.g. the food web diagram) constrains which combinations of positive and negative species responses to pest control are possible. We show how Boolean analysis of these combinations can be used to summarise the model predictions and present it in a way that is interpretable to conservation decision-makers. Importantly, the predictions obtained in this way subsume the various contradictory predictions that might be obtained from a probabilistic approach, and do not require the modeller to implicitly overstate their knowledge about the system by specifying a parameter space and sampling distribution.

To facilitate uptake of our methods, the paper is accompanied by tutorials, explanatory notes, and worked examples showing the links between various Qualitative Modelling methods and our own. You can read an early version of the paper, together with the tutorials etc. in the supplementary section, here. The tutorials are also available as Jupyter notebooks, which can be downloaded from the Github repository (click on files with a .ipynb extension for a preview).

My previous blog posts on the topic:

A brief overview of the Principle of Indifference

How the problem of the Principle of Indifference arises in an ecological modelling application