Some notes on the Principle of Indifference

A classical statement of the Principle of Indifference (PI) is as follows (p. 45 Keynes, 1921):

if there is no known reason for predicating of our subject one rather than another of several alternatives, then relatively to such knowledge the assertions of each of these alternatives have an equal probability. Thus equal probabilities must be assigned to each of several arguments, if there is an absence of positive ground for assigning unequal ones.

The various forms of PI encompass two ideas (Norton, 2008). First is a truism of evidence: if we have no grounds for distinguishing outcomes, then we should favour them equally. Here favouring can be epistemic, in the sense that it expresses our degree of belief; or it can be objective, in the sense that it expresses the extent to which our evidence supports the outcome. The second idea is that the extent of favouring is represented by a probability.

An example where PI works well - tossing a die: If a die is tossed, we have no reason to favour any one outcome over any other. So we treat each outcome 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 equally and assign the same probability to each.

Assigning equal probabilities to discrete outcomes can be generalised to the continuous case by assign a uniform probability distribution.

Another example: If a blindfolded person tosses a penny on a floor covered by equal-width planks, then we assign the same probability of landing on each plank. If we reduced the planks to infinitesimally small-widthed planks, we would approach the uniform distribution.

However PI gives different assignments of probability according to how we describe the outcome space, and in cases of very little little knowledge, we have no means to privilege one description as the correct one. As a consequence, PI can give mutually incompatible probability assignments depending upon the outcome space chosen and the way in which it is partitioned. A number of paradoxical examples have been devised in the literature to demonstrate how this occurs.

An example of a PI paradox - the squares factory (adapted from Smith, 2014): Imagine a factory that manufactures square plates with a length less than 2 m. PI recommends a uniform distribution of lengths between 0 and 2 m, which results in a prior belief of \(\frac{1}{2}\) that a plate’s length will be less than 1 m. However if one reframes the problem in terms of the plates’ areas, then PI recommends a uniform distribution between 0 and 4 m\(^2\), which results in a prior belief of \(\frac{1}{4}\) that a plate’s area will be less than 1 m\(^2\), which is equivalent to a prior belief that a plate’s length will be less than 1 m.

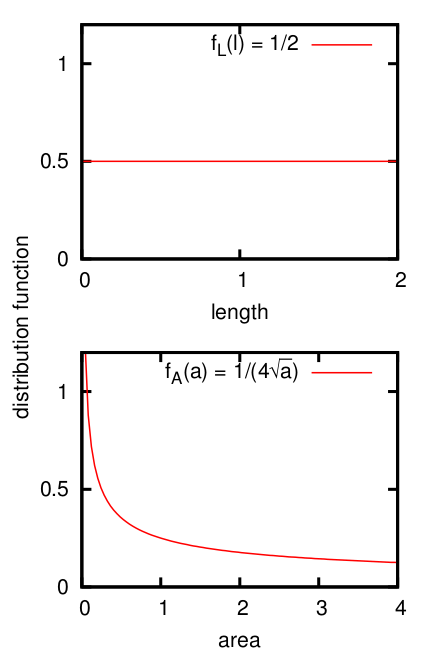

The reason that PI does not work well in the squares factory example is because a uniform distribution in the length of the square does not transform into a uniform distribution in the area of the square (see figure). Yet we have no reason to prefer length or area as the outcome space.

Details:

The length variable has support \(R_L = (0,2)\) and the random uniform distribution

\[f_L(l) = \begin{cases} 1/2 & \text{if } l \in R_L \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]giving the top panel of the figure.

The area is a function of the length

\[A = g(L) = L^2, \text{ so } L = g^{-1}(A) = \sqrt{A}\]Area has support \(R_A = \{ g(l) \mid l \in R_L \} = (0,4)\) and its distribution function is found with

\[f_A(a) = \begin{cases} f_L( g^{-1}(a) ) \left| \frac{ dg^{-1}(a) }{ da } \right| & \text{if } a \in R_A \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]giving the bottom panel of the figure.

Other famous PI paradoxes for further reading:

- von Mises’ wine/water paradox: A liquid is composed entirely a mix of wine and water. All we know is that the ratio wine/water is between 1/3 and 3. What is the probability that the ratio wine/water is less than 2? See Deakin (2006) for a discussion of two seemingly reasonable yet mutually incompatible proposed solutions.

- Bertrand’s paradox: Consider an equilateral triangle inscribed in a circle. Suppose a chord of the circle is chosen at random. What is the probability that the chord is longer than a side of the triangle? An easy-to-follow visual explanation of the paradox is available on its Wikipedia page. See Shackel (2007) for a discussion of proposed solutions and a rebuttal of them.

- Paradoxes arising from partitioning the space: The probability that a book is red is equal to the probability that a book is not-red. But the probability that a book is green is also equal to the probability that a book is not-green, and so on. See chapter 4 of Keynes (1921) for this and other similar paradoxes.

- Paradoxes arising from choosing structure versus state descriptors: Two coins are tossed. Should we assign \(1/4\) probability to each of {HH, HT, TH, TT}, or \(1/3\) probability to each of {2 H, 1H1T, 2T}? Mikkelson (2004) discusses this kind of problem.

Possible work-arounds for PI paradoxes

- Don’t use PI. Use an informative prior, obtained from the literature or via an `expert elicitation’ process (there is a large literature on the latter).

-

Use your intuition (`background knowledge’) about the process governing the system. For example (Jaynes, 1978):

> If we toss pennies onto a wooden floor, something inside us convinces us that the probability of landing on any plank should be taken proportional to the width of the plank; and not to the cube of the width, or the logarithm of the width. In other words, merely knowing the physical meaning of our parameters, already constitutes highly relevant prior information which our intuition is able to use at once; in favorable cases its effect is to give us an inner conviction that there is no ambiguity after all in applying the Principle of Indifference. - Treat the different predictions in different parameter spaces as separate hypotheses (p. 69 Keynes, 1921).

- Specify the reference class, by expressing the model predictions in terms of conditional statements, e.g. `the probability of a a square with area between \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) given that length is distributed like \(f(l)\) is …’. Hájek (2007) provides a very good discussion of the reference class problem, for both frequentist and epistemic probability.

- Use supervenience to select the appropriate parameter space (Mikkelson, 2004). A set of properties A supervenes upon another set B when no two things can differ with respect to A-properties without also differing with respect to their B-properties (see Stanford Enc of Phil). For example, in the two-coins paradox, we would use the space {HH, TH, HT, TT}.

- Find a prior that is invariant between parameter spaces. Burock (2005) provides an easy-to-follow example for the wine/water paradox, which involves applying PI to the joint sample space of the equivalent parameters. It should be noted however that invariance is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition. Many invariant transformations exist leading themselves to paradoxes involving which transformation to choose (Deakin, 2006; Norton, 2008). See also the Wikipedia page for `Principle of Transformation Groups’.

- Seek a method of representing degrees of favouring without using probabilities. Norton (2010) replaces the full continuous-valued probability with a three-valued system: (1) possible, (2) impossible, or (3) necessary; then the paradoxes no longer occur.

References

Burock, M. (2005). Indifference, sample space, and the wine/water paradox. URL: http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/2487/

Deakin, M. A. (2006). The wine/water paradox: background, provenance and proposed resolutions, Australian Mathematical Society Gazette 33(3): 200.

Hájek, A. (2007). The reference class problem is your problem too, Synthese 156(3): 563–585.

Jaynes, E. T. (1978). Where do we stand on maximum entropy?, The Maximum Entropy Formalism Conference pp. 15–118.

Keynes, J. M. (1921). A treatise on probability, MacMillan and Co. Ltd., London.

URL: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32625/32625-pdf.pdf

Mikkelson, J. M. (2004). Dissolving the wine/water paradox, British Journal for the Philosophy of Sciencepp. 137–145.

Norton, J. D. (2008). Ignorance and indifference, Philosophy of Science 75(1): 45–68.

Norton, J. D. (2010). Cosmic confusions: not supporting versus supporting not-, Philosophy of Science 77(4): 501–523.

Shackel, N. (2007). Bertrand’s paradox and the Principle of Indifference, Philosophy of Science 74(2): 150–175.

Smith, M. (2014). Evidential incomparability and the Principle of Indifference, Erkenntnis 80(3): 605–616.