Carryover effects and local adaptation

What allows a population in a heterogeneous landscape to become locally adapted? In general, adaptation to a rare habitat type is difficult because divergent selection is counter-acted by the homogenising effects of gene-flow. However adaptation to a rare habitat type may occur if it has a higher quality, so that a greater number of offspring can be produced there, to compensate for its relative rarity in the landscape.

In a new paper published in Ecology Letters, we focused on an alternative way in which a habitat may be considered to have higher quality: by increasing the quality, rather than the quantity, of offspring produced.

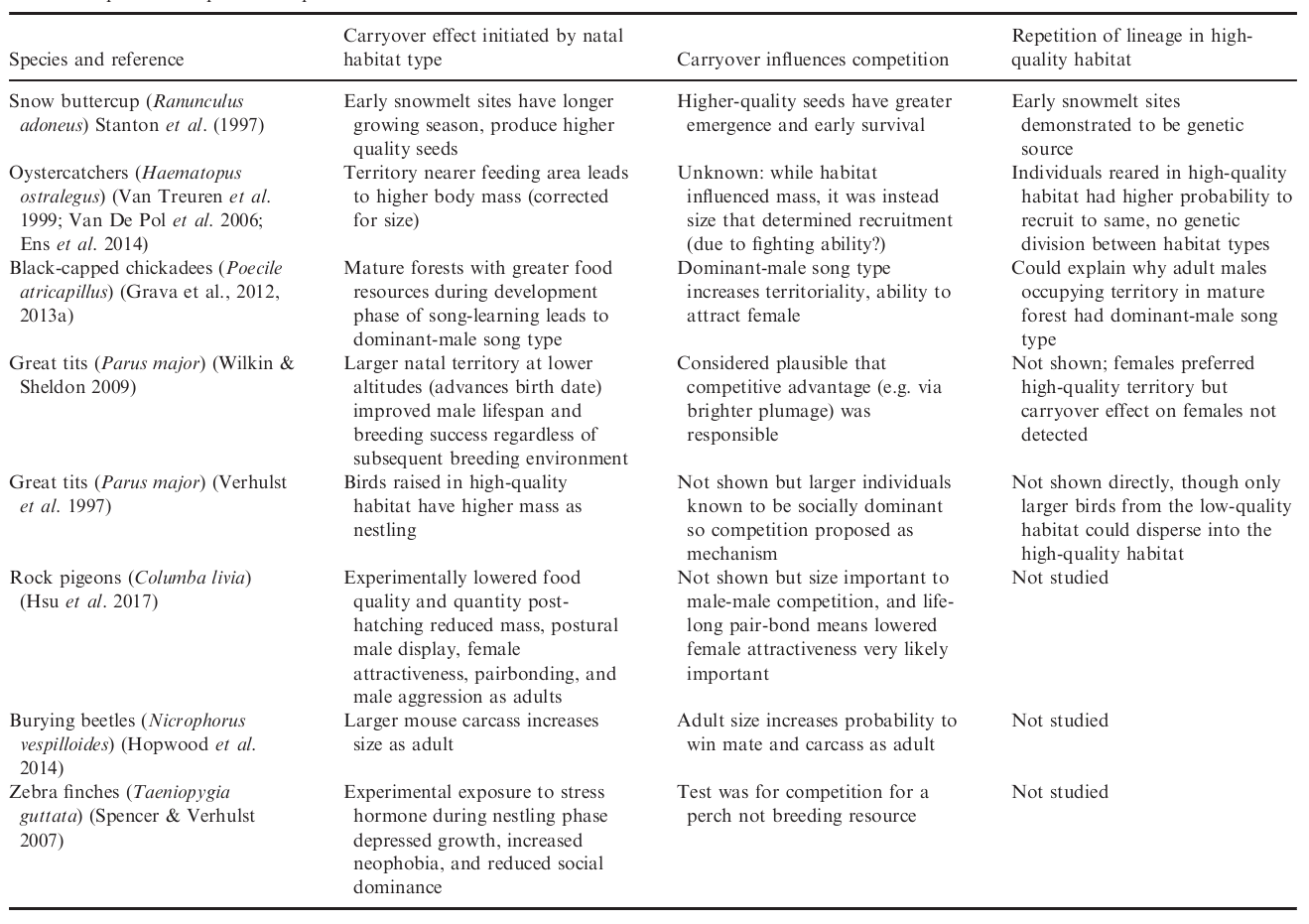

There are many examples where the natal habitat effects the quality of an offspring, and that effect carries over to its quality as an adult (see Table). We were particularly interested in carryover effects on competitive ability. For example, a chick who is raised in a resource-rich environment may develop into an adult who is better at singing (e.g. Grava et al., 2012, 2013a) and larger than other birds (e.g. Van Treuren et al. 1999; Van De Pol et al. 2006; Ens et al. 2014) and so better able to attract a mate and win a breeding territory. We wondered if such carryover effects could also also permit adaptation to a rare habitat type, counteracting gene flow from a more-common but lower-quality habitat type.

We were particularly interested in the idea that an offspring raised in a high-quality habitat will be more likely, as a highly-competitive adult, to win a similarly high-quality territory and raise its own offspring there (i.e. the silver spoon competition hypothesis of Stamps 2006). So we mathematically tracked the following intuition. If dispersal distance is limited, competitively superior individuals accumulate in the high-quality habitat, forming a competitive barrier to immigrants from nearby low-quality habitat. A positive feedback will emerge that promotes a lineage’s repeated encounters with the high-quality habitat type, which in turn may promote selection to adapt to this habitat type. Meanwhile, adaptation to the more common low-quality habitat type is preserved, due to the relatively low contribution that individuals from high-quality habitat make to the gene pool there.

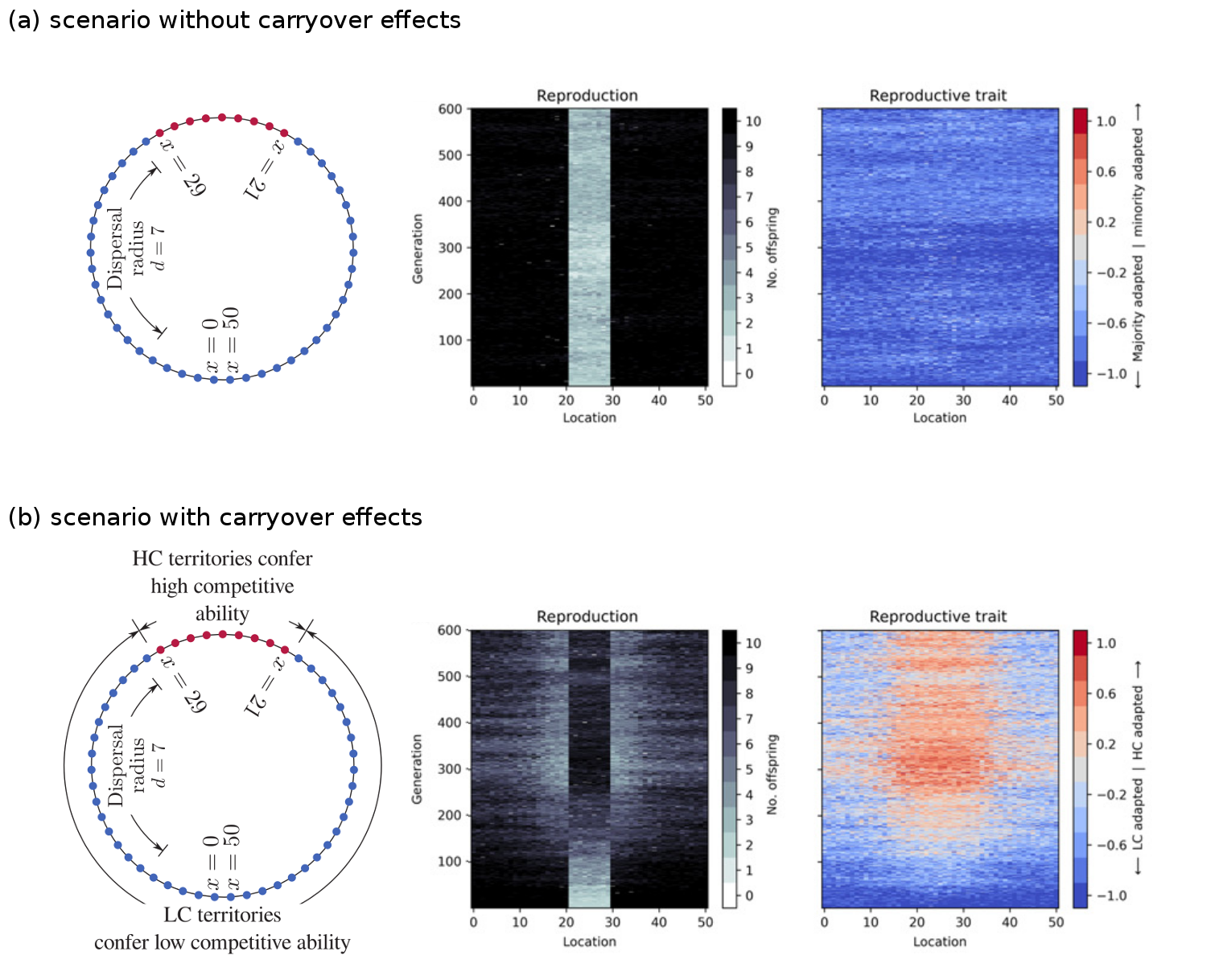

We created an individual-based, genetically and spatially explicit model of a single population on a landscape consisting of two habitat types. The figure below shows the first key result of the paper. In the absence of any differences in habitat quality (panel a), the population will adapt to the habitat type that is most frequent in the landscape (blue). However, when the rarer habitat type (red) confers a competitive advantage upon offspring raised there (panel b), then the population splits into two ecotypes, each relatively well-specialised to one of the two habitat types (red and blue).

The model involved a landscape, shown as a ring, with territories of two different habitat types, shown as blue and red. Offspring could disperse up to a distance of 7 territories away. We tracked through time the reproduction rate, and the evolution of a reproductive trait to see if the population would adapt to the blue or red habitat type. As expected, in the absence of any carryover effects, the population evolved to be more adapted to the common blue type and maladapted to the rare red type (a). In that case the reproduction rate in the red habitat is low and a source-sink ecological dynamic emerges. However, when the rare red habitat type has a carryover effect, such that offspring raised there are more competitive, then the population split into two ecotypes, with one more adapted to the red and one more adapted to the blue habitat type (b).

Our second model result is that, once trait divergence has been initiated, then it can be subsequently reinforced by the coevolution of dispersal traits that promote matching between an individual’s ecotype and habitat type (‘ecotype-habitat matching’). Ecotype-habitat matching dispersal traits include a short dispersal distance and high natal-habitat preference (Davis & Stamps 2004). In turn, these dispersal traits strengthened local adaptation, creating a positive feedback loop between them. The evolution of ecotype-habitat matching dispersal traits is stronger the rarer the high-quality habitat is: first, because a smaller geographic size means that selection against dispersal outside of its boundaries is stronger, and second, because a smaller subpopulation makes it more likely for a correlation between local-adapted genes and ecotype-habitat matching dispersal genes to occur spontaneously due to stochastic process.

We believe that a comparison of blue tit populations on the French mainland vs. the island of Corsica (reviewed in Charmantier et al. 2016) may provide an empirical example of the mechanisms in our model. On the mainland, the majority habitat type is deciduous, and blue tits who settle in the rarer evergreen patches are maladapted (Blondel et al. 1993), resulting in source-sink dynamics (Dias & Blondel 1996; Dias et al. 1996). On Corsica however, where evergreen habitat dominates, the source–sink pattern is not simply reversed. Instead, trait divergence into two ecotypes has been documented (Porlier et al. 2012). We think the reason that the reason for this difference in ecoevolutionary outcomes is because the deciduous habitat type has a higher quality and confers a competitive advantage to offspring raised in it. In the paper we discuss the evidence for this, including the phenological differences between the habitat types and its effect on social dominance (Braillet et al. 2002). We also note that blue tits on Corsica have reduced dispersal which matches the predictions of our model.

Finally we propose that carryover effects as described by our model may provide a previously overlooked mechanism to initiate isolation by ecology. In current theory, isolation by ecology (Shafer & Wolf 2013) is initiated by divergent selection that is strong enough to counteract gene flow (Nosil 2007; Nosil et al. 2008). This creates a positive feedback in which local adaptation leads to a further reduction in realised gene flow between ecotypes (Rundle & Nosil 2005). In our model, the gene flow barrier is initiated by the effect of the environment upon the phenotype rather than as a genetic effect.

Paper details

Kristensen, N.P., Johansson, J., Chisholm, R.A., Smith, H.G., Kokko, H. (2018) Carryover effects from natal habitat type upon competitive ability lead to trait divergence or source-sink dynamics, Ecology Letters, in press, (open access), (Github)

References

Blondel, J., Dias, P.C., Maistre, M. & Perret, P. (1993). Habitat heterogeneity and life-history variation of Mediterranean blue tits (Parus caeruleus). Auk, 110, 511–520.

Braillet, C., Charmantier, A., Archaux, F., Dos Santos, A., Perret, P. & Lambrechts, M.M. (2002). Two blue tit Parus caeruleus populations from Corsica differ in social dominance. J. Avian Biol., 33, 446–450.

Charmantier, A., Doutrelant, C., Dubuc-Messier, G., Fargevieille, A. & Szulkin, M. (2016). Mediterranean blue tits as a case study of local adaptation. Evol. Appl., 9, 135–152.

Davis, J.M. & Stamps, J.A. (2004). The effect of natal experience on habitat preferences. Trends Ecol. Evol., 19, 411–416.

Dias, P.C. & Blondel, J. (1996). Local specialization and maladaptation in the Mediterranean blue tit (Parus caeruleus). Oecologia, 107, 79–86.

Dias, P., Verheyen, G. & Raymond, M. (1996). Source-sink populations in Mediterranean blue tits: evidence using single-locus minisatellite probes. J. Evol. Biol., 9, 965–978.

Ens, B.J., Van de Pol, M. & Goss-Custard, J.D. (2014). The study of career decisions: oystercatchers as social prisoners. Adv. Study Behav., 46, 343–420.

Grava, T., Grava, A. & Otter, K.A. (2012). Vocal performance varies with habitat quality in black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). Behaviour, 149, 35–50.

Grava, T., Fairhurst, G.D., Avey, M.T., Grava, A., Bradley, J., Avis, J.L. et al. (2013a). Habitat quality affects early physiology and subsequent neuromotor development of juvenile Black-capped Chickadees. PLoS ONE, 8, e71852.

Nosil, P. (2007). Divergent host plant adaptation and reproductive isolation between ecotypes of Timema cristinae walking sticks. Am. Nat., 169, 151–162.

Nosil, P., Egan, S.P. & Funk, D.J. (2008). Heterogeneous genomic differentiation between walking-stick ecotypes: ‘isolation by adaptation’ and multiple roles for divergent selection. Evolution, 62, 316–336.

Porlier, M., Garant, D., Perret, P. & Charmantier, A. (2012). Habitat-linked population genetic differentiation in the blue tit Cyanistes caeruleus. J. Hered., 103, 781–791.

Rundle, H.D. & Nosil, P. (2005). Ecological speciation. Ecol. Lett., 8, 336–352.

Shafer, A. & Wolf, J.B. (2013). Widespread evidence for incipient ecological speciation: a meta-analysis of isolation-by-ecology. Ecol. Lett., 16, 940–950.

Stamps, J.A. (2006). The silver spoon effect and habitat selection by natal dispersers. Ecol. Lett., 9, 1179–1185.

Van De Pol, M., Bruinzeel, L.W., Heg, D., Van Der Jeugd, H.P. & Verhulst, S. (2006). A silver spoon for a golden future: long-term effects of natal origin on fitness prospects of oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus). J. Anim. Ecol., 75, 616–626·

Van Treuren, R., Bijlsma, R., Tinbergen, J., Heg, D. & Van de Zande, L. (1999). Genetic analysis of the population structure of socially organized oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) using microsatellites. Mol. Ecol., 8, 181–187.

(A link to a previous blog post when I first became interested in the blue tits case study.)