Migratory bird phenology

Collaborators: Jacob Johansson, Jorgen Ripa, Niclas Jonzen, Theoretical Population Ecology and Evolution Group, Lund University

Kristensen, N.P., Johansson, J., Ripa, J., Jonzen, N. (In press) Phenology of two interdependent traits in migratory birds in response to climate change, Proceedings of the Royal Society B

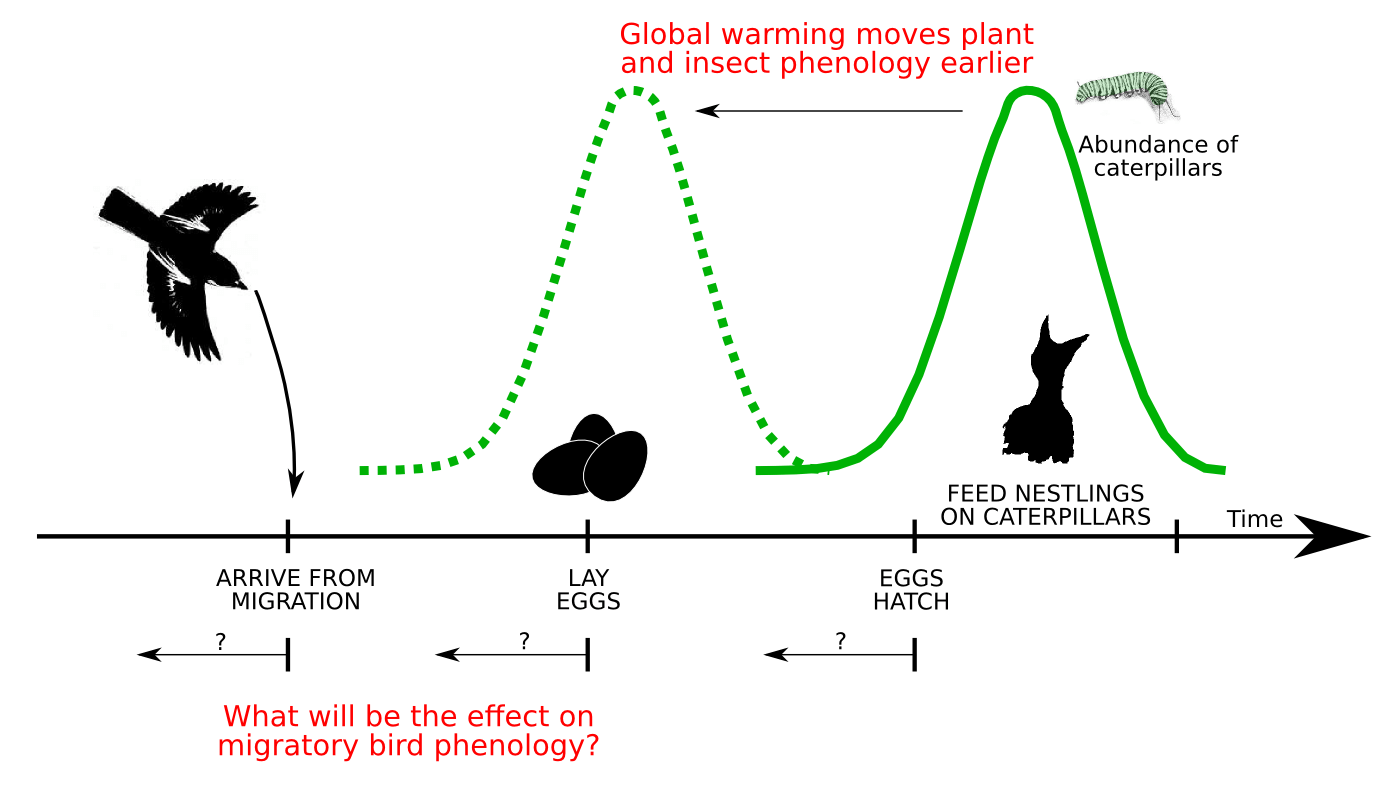

Climate change leads to an earlier arrival of spring warming. This affects the phenology of many species (Forchhammer et al. 1998, Chmielewski & Rotzer 2001, Parmesan & Yohe 2003, Edwards & Richardson 2004, Menzel et al. 2006, Beebee 2009). For example, in migratory birds, the effects can flow up the trophic levels. Earlier warm temperatures leads to earlier plant budding (Menzel et al. 2006, Schwartz et al. 2006, Primack et al. 2009). Earlier plant budding leads to earlier peaks in the numbers of caterpillars in the forest. And migratory birds, for whose nestlings these caterpillars are an important food source, are pressured to advance their own breeding timetable to keep pace with the changes (Visser et al. 1998).

In general, birds have responded to warming weather by advancing their own phenology. Migratory birds are both arriving earlier (Huppop et al. 2003, Parmesan & Yohe 2003, Drent et al. 2003, Lehikoinen et al. 2004, Jonzen et al. 2006) and laying earlier (Crick et al. 1997, Crick & Sparks 1999, Both et al. 2004) in recent years. However, the responses have not been uniform. Different populations of even the same species have quite different phenological responses. For example, Both (2010) contrasted a population of Dutch flycatchers to Finnish flycatchers, the former advanced their laying date but not arrival date, and the latter advanced arrival but not laying. What is it that determines which aspect of the phenology shifts?

Most worrying from a conservation perspective, in some populations the advance in arrival time and laying time has not kept pace with the advance in the food peak. This creates a `mismatch’ between hatching time and nestling food (e.g. Both & Visser 2001, Both et al. 2006). Such mismatches have been implicated in population declines (Both et al. 2006, Goodenough 2009).

A mismatch and a failure to keep pace with climate change can be attributed to many things. One might intuit that the effects of warming will flow back through the breeding timetable. So an advance in the caterpillar date will put pressure to advance hatching, which will advance laying, which will advance arrival. Consequently a mismatch is often attributed to inflexibility in the arrival date due to external factors constraining adaptation (Both & Visser 2001, Drent et al. 2003). A bird like the pied flycatcher migrates all the way from Africa to Europe (Lack 1968). Maybe the cues that it uses to start that migration and time its stopovers are not sensitive enough to changes in the warming in Europe?

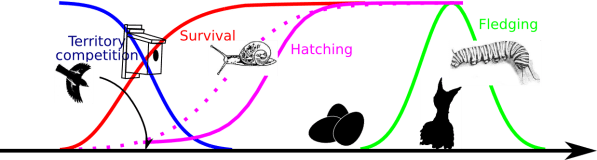

Though are we sure that a mismatch means what we think it means? There is a growing literature suggesting that mismatch may be adaptive in certain circumstances (Singer & Parmesan 2010, Visser et al. 2012, Johansson & Jonzen 2012b) and there is some evidence that birds were mismatched historically (Lack 1968; Perrins 1970; Perrins & Moss 1975; Drent 2006). The problem facing the bird is not so simple as to purely match nestlings to the caterpillar peak. Each of the aspects have other effects on the fitness of the individuals, and an improvement in one aspect may lead to a loss in another.

Consider the problem of arrival date. The probability of adult survival is dependent upon the arrival date such that early arrival imposes a greater survival cost. This reflects food scarcity and harsh weather conditions on arrival (Newton 2007, Kokko 1999). However early arrival also confers a fitness benefit: the probability that the male will obtain a quality breeding territory to subsequently attract a mate and produce a clutch (Brooke 1979, Arvidsson & Neergaard 1991, Lundberg & Alatalo 2010, Aebischer et al. 1996, Lozano et al. 1996, Kokko 1999). So birds must arrive early enough to compete and acquire a quality nesting site, but not so early that they die in early-season cold weather.

But the arrival date may also constrain the hatching date. Once the bird has arrived, it must gather resources for egg production (Perrins 1970, Nager 2006). Even if it is a capital breeder, key nutrients like calcium (available from snail shells) will need to be gathered at the breeding site (Perrins 1996, Mand Tilgar & Leivits et al. 2000). The longer the prelaying period is the better the female body condition and clutch size possible (Rowe et al. 1994, Pettifor et al. 2001, Descamps et al. 2011) and the more egg-specific resources that can be gathered for manufacturing the egg (Nager 2006). However, resource availability during the pre-laying period is variable (Gauthier 1993), with food availability lower earlier in the season (Perrins 1970), and birds expending more energy during cold conditions (te Marvelde et al. 2012). This implies that the rate at which key nutrients for egg-production can be acquired will also be dependent upon how early in the season the prelaying period is, and thus also a function of arrival time. For example snails, which are a good source of the calcium needed for making eggs, have their own phenology and timing of availability (e.g. Bailey 1975).

So the problem of mismatch of hatching to caterpillar peak is actually a problem about the whole breeding timetable, about all of the effects that the timing of each phenological event has on fitness, and the ways in which the timing of those events affect one another.

In our recent work we have taken the two key phenological traits used as markers for climate change - arrival date and hatching date - gathered together what we know about their likely fitness effects and interactions (carryover effects notwithstanding (Catry 2013)), and modelled their evolution using the adaptive dynamics framework. We ask, even assuming that the birds were able to adapt perfectly to climate change, will mismatch occur, and in what way? Will arrival date advance, will hatching advance, will both? And under what circumstances can we expect which changes?

Related blog posts:

- Are caterpillars really that important? (21 May 2014)

- Do birds sometimes respond to warming temperatures by delaying their phenology? (9 April 2013)

- What is the relationship between lay date, mismatch, and overall fitness for migratory birds? (10 January 2013)

- The problem of arrival time and prelaying period in migratory birds (13 October 2012)

Publications:

Kristensen, N.P., Johansson, J., Ripa, J., Jonzen, N. (In press) Phenology of two interdependent traits in migratory birds in response to climate change, Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Johansson, J., Kristensen, N.P., Nilsson, J., and Jonzen, N. (2015) The eco-evolutionary consequences of interspecific phenological asynchrony: a theoretical perspective, Oikos 124(1):102-112.