Large community evolution models

Several reviews exist on the influence of evolution on food-web structure (Yoshida, 2006; Fussman et al., 2007; Loeuille & Loreau, 2009; Loeuille, 2010). In Brannstrom et al. (2008), we reviewed past theoretical modelling efforts to study food web structure, and the current state of large community evolution models to tackle the problem.

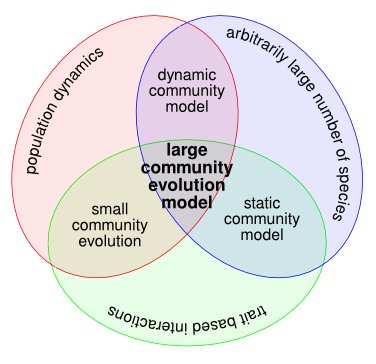

Schematic illustration of the community models that were considered in our review. We started out by surveying static and dynamic ecological models, which do not possess an evolutionary component. After this, we moved on to evolution in small community models. Finally, we reviewed large community-evolution models, which synthesise elements of all aforementioned model types.

The past decade has seen burgeoning growth in the development of large community food web models with an evolutionary component. Examples include Webworld (Drossel et al. 2001), Tangled Nature (Christensen et al. 2002), the Matching Model (Rossberg et al. 2006), Ito & Ikegami’s diffusion model (2006), and Louielle & Loreau’s body-size based model (2005).

These models combine aspects from two previous lines of modelling: dynamic community models models like Law & Morton (1996), particularly the assembly algorithm approach, and small community evolution like adaptive dynamics (Dieckmann, 1997).

What sets these models apart from the community assembly models that precede them (above) is that, because species are typically defined in terms of evolvable traits, their interactions with other species are a function of these traits, which allows species to evolve into new ecological roles. Also, while assembly models typically involve exposing the model community to a series of invasions by species from an external pool, in evolutionary models the “invaders” are internally generated e.g. mutants of the species present. This removes the need to justify the make-up of the invader-pool used, however most evolutionary models can easily be modified to include invasion from alien species.

Recent increases in computational power have allowed for the simultaneous incorporation of ecological complexity and evolutionary dynamics in theoretical models. However typically, large-community evolution models are not simply larger versions of the small evolutionary models that preceded them. There is a striking diversity in the precise way in which evolutionary change is modelled: as a diffusion process in trait space (Ito & Ikegami, 2006), as point mutations in binary strings (Drossel et al., 2001; Christensen et al., 2002), as changes in contribution of allelic effects in strings (Yoshida et al., 2003), as small-to-large mutational steps in a continuous trait values (e.g., Loeuille & Loreau, 2005), or as gradual mutational steps in continuous trait values (e.g., Ripa et al., 2009; Brännström et al., 2011).

The trait-based approach of large-community evolutionary models can also be compared with static community models (Williams & Martinez, 2000), in that both emphasise the effect of the niche on food web structure, and recent models have used the same empirical data set and methods of assessing the validity of the models (Louielle & Loreau 2005). One of the frustrating aspects of the static community models is that, although they perform best and reproducing real food web structure, the meaning of the niche-value and reason why it should be hierarchically ordered continues is vague (Williams and Martinez 2000, Dunne 2006). It has been suggested that the niche-value represents body size (Cohen & Newman 1985), or perhaps some other phylogenetic aspect (Cattin et al. 2004), though it is never made explicit. Regardless, the discussion around it does point to some species-level or trait-based organising concept, which hints that a trait-based approach like the large evolutionary models may provide insights into food web structure.