Evolution of cooperation

When people play public goods games in lab-based experiments, they often cooperate even though it goes against their self interest. Many authors have pointed out the ways in which such experiments can be unrealistic, e.g., by enforcing anonymity between participants, and they have discussed how the incentives in a one-shot encounter differ from when interactions are repeated within the same group. In our recent paper, we focused on another common assumption that has received less attention: the benefits in real-life public goods games are almost never linear. We were interested in the implications of this nonlinearity for the evolution of human cooperation.

Consider, for example, the method used by Australian Aborigines in southwestern Victoria to hunt kangaroos. As discussed in Balme (2018), in the early nineteenth century, communal gatherings were associated with mass-scale hunting of kangaroos and emus. People would form a large circle 25-30 km in diameter. Then they would then move inwards, yelling to frighten the animals, until they were concentrated in a small area where they could be killed. Obviously, these were modern hunter gatherers, and the hunts were just one small part of the activities that attracted participants from hundreds of kilometres away. Nevertheless, we can imagine that our much earlier ancestors might have struck upon a similar but much smaller-scale method of hunting.

Figure 1. Kangaroos in their native grassland habitat. Contributed to Wikipedia by user AWS10.

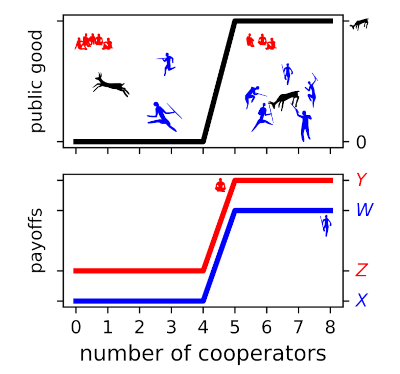

Let’s consider what the benefits function of this encircling technique might look like. A single individual cannot successfully encircle the animals. As the number of hunters increases, at first the likelihood of success is small, but the likelihood increases at an increasing rate. However, once the number of hunters reaches a certain level, the animals are already surrounded, and additional hunters become increasingly superfluous. Therefore, we can expect something like a sigmoid relationship between the number of hunters and the benefit. In the most extreme case, the benefits function would have a threshold shape: a minimum number of hunters is needed to surround the prey, and beyond that, additional hunters make no difference (Fig. 2). This threshold game is an \(n\)-player generalisation of the 2-player Stag Hunt.

Figure 2. A hypothetical threshold public goods game involving a prehistoric hunt. A minimum number of hunters (5) must cooperate to successfully surround and kill an animal or their efforts are wasted. A cooperator’s payoff is (W) if the threshold is met and (X) if it is not (blue line). All members share the meat ((n = 8)); therefore, the highest payoff goes to defectors (red line) regardless of whether the hunt is successful (payoff (Y)) or not (payoff (Z)). However, if an individual is likely to be the pivotal hunter, i.e., the hunter that brings the group above the threshold for a successful hunt, then they are incentivised to cooperate. The incentive is that the payoff to a defector when the threshold is not met is less than the payoff to a cooperator when the threshold is met ((Z < W)).

We expect that a group who hunts together will include some family members; however, modelling kin selection in groups is difficult when the benefits function is nonlinear. In short, unlike 2-player interactions, where the model can parameterised with single relatedness factor (i.e., Hamilton’s \(r\)), in group interactions, the model must account for all possible combinations of types within the group, which means accounting for all possible kin + nonkin combinations. For a more detailed discussion of this, see Allen & Nowak (2016), particularly Eq. 6; and Van Cleve (2015), particularly Eq. 21.

Hisashi Ohtsuki gave a recipe for describing the dynamics in terms of those kin + nonkin combinations (Ohtsuki, 2014). Let \(a_k\) and \(b_k\) be the payoff functions for Cooperators and Defectors, respectively, when \(k\) of the other \(n-1\) group members are Cooperators. Then the change in the proportion of Cooperators \(p\) in the population is

\[\begin{equation} \Delta p \propto \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \sum_{l=k}^{n-1} (-1)^{l-k} {l \choose k} {n-1 \choose l} \left[ (1-\rho_1) \rho_{l+1} a_k - \rho_1(\rho_l - \rho_{l+1}) b_k \right]. \tag{1} \end{equation}\]where

\[\begin{equation} \rho_l = \sum_{m=1}^l \theta_{l \rightarrow m} p^m. \label{rho_l} \tag{2} \end{equation}\]The \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) in Eq. 2 are called the higher-order relatedness coefficients, and they can be thought of as generalisations of the dyadic relatedness coefficient, Hamilton’s \(r\), to \(l\) individuals. Relatedness \(r\) is the probability that, if we draw 2 individuals without replacement from the group, they will share a common ancestor and therefore their strategy will be identical by descent. \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) is the probability that, if we draw \(l\) individuals without replacement from the group, they will share exactly \(m\) common ancestors.

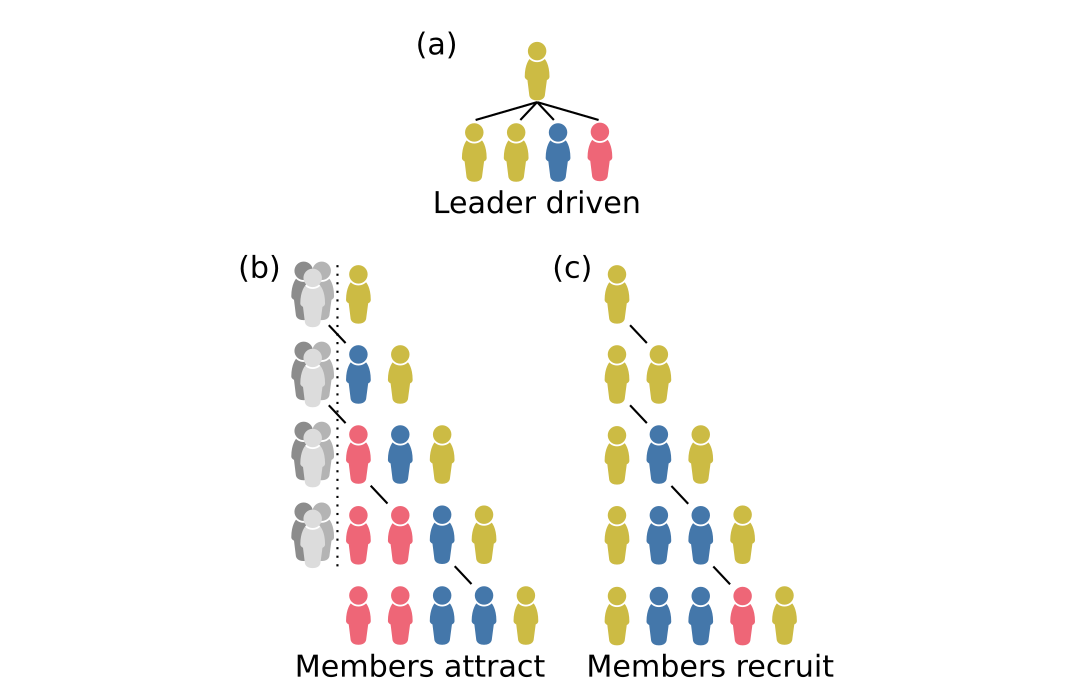

However, Ohtsuki (2014) did not provide a general method for obtaining the \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) parameter values. In our paper, we created 3 homophilic group-formation models that allowed us to parameterise Eqns. 1 and 2 (Fig. 3). In short, we assumed that groups are formed sequentially by current members attracting/recruiting new members. We modelled homophily (the tendency to attract similar others) as an exogenous parameter, and when homophily is high, new members are more likely to be kin of an existing member and thus identical by descent.

Figure 3. Examples of a group of five individuals forming according to the rules of the three homophilic group-formation models: (a) leader driven, (b) members attract, and (c) members recruit. In the leader-driven model, only the leader recruits/attracts new members, and they recruit/attract a kin with probability (h) and nonkin with probability (1-h). In the members-attract model, every member has an equal chance to attract a new member who is kin, but nonkin are also attracted to the group itself with constant collective weighting that has a negative relationship with (h). In the members-recruit model, every member has an equal chance to recruit the next new member, and they recruit a kin with probability (h) and nonkin with probability (1-h).

We were interested in the question of how cooperation in non-linear games first arose. We know that, for a benefits function shaped like the hunting examples above, provided the function and game have suitable parameter values, then once the number of cooperators in the population is high enough, a coexistence between cooperators and defectors is evolutionarily stable. Peña et al. (2014) provides a particularly beautiful way to analyse this mathematically. However, the ancestral state was presumably a population of all defectors, and it can also be shown cooperators cannot invade a population of all defectors, which raises the question of how cooperation got started in the first place.

To understand why cooperators can persist but cannot invade, we can think about the one-shot threshold game as an example (Fig. 2). If you are in a group with complete strangers, you have no kinship or friendship incentives to cooperate. If the interaction is anonymous, you have no reputational incentives. If the game is a one-shot interaction, you know that you will never meet these people again, so you have no reciprocity / fear-of-punishment incentives, either. Nevertheless, it can still make sense to cooperate in a threshold game. If others in your group are likely to be cooperators, then cooperation may be in your self interest because your contribution might be the one to push the public-goods benefit above the threshold. Thus, cooperation can persist evolutionarily. However, if cooperation is very rare in the population such that you’re likely to be the only cooperator in the group, then it doesn’t make sense to cooperate because your lone contribution will not be enough to obtain the public good. Therefore, the first cooperators could never gain a foothold in the population and thus cooperation could never evolve.

However, the reasoning above assumes groups are formed at random with non-family members / strangers. In our paper, we showed that if groups in the past tended to include family members, then cooperation could evolve. If instead of being grouped with strangers, you are in a group with family members, then if you are a cooperator, your fellow group members are likely to be cooperators as well because they share your genes. This positive assortment between cooperators means that cooperation can gain a foothold in the population, and cooperation can evolve.

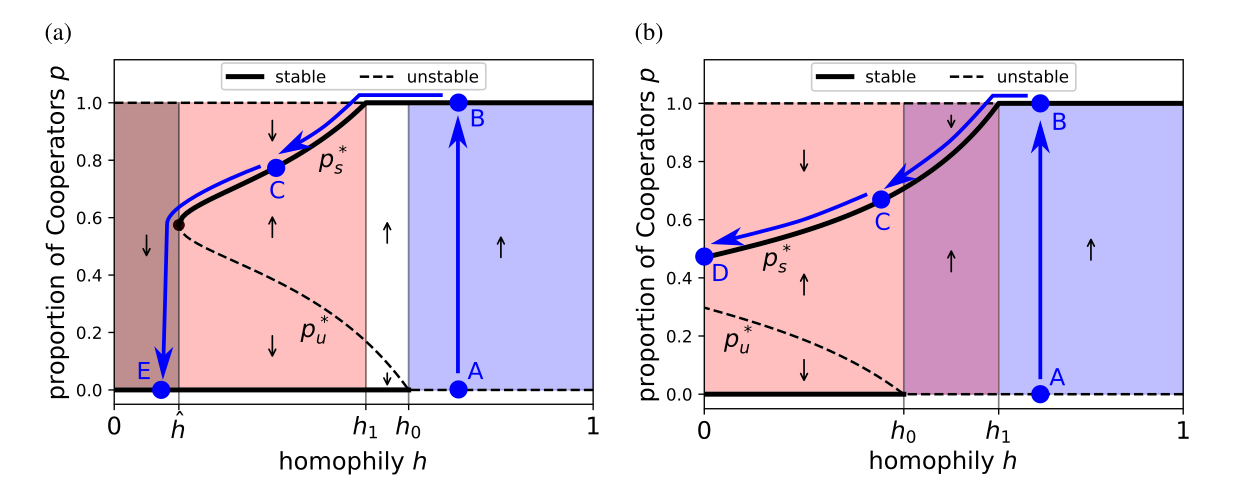

In addition, once cooperation has evolved by kin selection, then even if circumstances change and recruitment of strangers becomes more common, cooperation can nevertheless persist. Whether or not it persists depends on how much homophily is lost and the parameter values in the game (Fig. 4), but it is possible for cooperation to persist in some circumstances even if homophily is lost altogether (Fig. 4(b)).

Figure 4. Two examples of how genetic homophily affects the evolutionary dynamics in our model, showing possible trajectories of cooperation as human homophily decreased over time due to changing social environments (blue lines). The evolutionary dynamics separates into qualitatively different regimes depending on the homophily level (h): Cooperators cannot persist (dark shading), Defectors can both invade and persist (red shading), and Cooperators can invade (blue shading). In the ancestral past, homophily was high (point A), which allowed Cooperators to invade (B). As homophily decreased (decreasing (h)), Cooperation persisted even into the region where it could not invade (C). Depending on the parameter values, Cooperation can either persist even if homophily disappears entirely (D), or Cooperation will be lost below a certain level of homophily (E).

So why do people cooperate in lab-based public goods games? A lot of attention has been paid to the fact that lab-based games are unrealistic: we often interact with people we will meet again and we are rarely truly anonymous, so the social heuristics we use for daily life lead us astray in this artificial environment. We emphasise that another way lab games are unrealistic is that people are not used to playing linear games, and we speculate that this might explain some of the cooperative behaviour.

There is some evidence supporting the idea that people in lab-based games behave as though they’re playing a nonlinear game. People generally prefer to condition their contributions on the level of contribution from others (Fischbacher et al 2001, Chaudhuri 2011, Thöni & Volk 2018), which only makes sense from a self-interested perspective if the game is nonlinear. They will even do this when playing against a computer, which suggests that this behaviour isn’t purely about a sense of fairness or caring for the welfare of others (Burton-Chellew et al. 2016). Chat logs from computer-networked games also reveal a common misperception of linear games as some type of coordination problem (Cox & Stoddard 2018) like a threshold game. Thus, it seems likely that some people are just genuinely confused about what the self-interested payoff-maximising strategy is when the game is linear, and they expect payoffs similar to a nonlinear game.

Our idea that people cooperate because they are “confused” is similar to the evolutionary maladaptionhypothesis; however, there are some key differences, as well. Roughly speaking, the evolutionary maladaptation hypothesis is the idea that when humans cooperate with strangers, we basically do so because our behavioural programming mistakes those strangers for kin (Burnham et al. 2005, Hagen & Hammerstein 2006, El-Mouden et al. 2012). For most of our evolutionary history, we have lived in small groups composed mostly of relatives. In that environment, indiscriminately cooperating with others around you was a good strategy because chances were they were your relatives. However, our social environment has changed very rapidly recently, in evolutionary terms, so that now we often interact with nonkin, and evolution hasn’t yet had a chance to catch up. Thus our behaviour is “maladaptive” because cooperating with relatives provided inclusive fitness benefits, whereas cooperating indiscriminately with strangers does not.

In contrast, in our model, cooperating with strangers is not maladaptive. Although past kin selection is needed to explain how cooperation first got started, once it is established in the population, cooperating with strangers can be in one’s self interest.

Our model also implies a different narrative about how/why cooperation persisted as humans transitioned from mostly interacting with family to interacting with nonkin. In the evolutionary maladaptation hypothesis, cooperation was extended to nonkin maladaptively due to, e.g., rapidly increasing population size. This seems to imply somehow that cooperating with nonkin was an “easy” mistake to make. In our model, cooperation persisted because it was evolutionarily stable. We expect that it might have been quite challenging to extend cooperation to nonkin because that means overcoming kin bias and a suspicion of strangers or outgroup members. Our view seems to sit more easily with cross-cultural empirical studies showing that cooperative behaviour with strangers/nonkin is not as universal in small-community societies as it is in societies with high market integration, etc. (Henrich et al. 2005, Henrich et al. 2010).

Our work is published now in Scientific Reports, and we are currently working on extending these modelling techniques from situations with only 2 strategies to many strategies (Cooperate, Defect, Coordinate, Punish, etc.).

References

Allen, B. and Nowak, M. A. (2016). There is no inclusive fitness at the level of the individual, Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 12:122-128.

Balme, J. (2018). Communal hunting by Aboriginal Australians: Archaeological and ethnographic evidence. In Manipulating Prey: Development of Large-Scale Kill Events Around the Globe, eds Carlson, K. & Bemet, L., University of Colorado Press, Boulder, Colorado, 42062.

Burnham, T. C. & Johnson, D. D. (2005). The biological and evolutionary logic of human cooperation. Anal. Kritik 27, 113-135.

Burton-Chellew, M. N., El Mouden, C. & West, S. A. (2016). Conditional cooperation and confusion in public-goods experiments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113:1291-1296.

Chaudhuri, A. (2011). Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: A selective survey of the literature. Exp. Econ. 14, 47-83.

Cox, C. A. & Stoddard, B. Strategic thinking in public goods games with teams. J. Public Econ. 161, 31–43 (2018).

El-Mouden, C., Burton-Chellew, M., Gardner, A. & West, S. A. (2012). What do humans maximize? In Evolution and Rationality: Decisions, Cooperation and Strategic Behaviour, eds Okashi, S. & Binmore, K., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 23-49.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S. & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 71, 397-404.

Hagen, E. H. & Hammerstein, P. (2006). Game theory and human evolution: A critique of some recent interpretations of experimental games. Theor. Popul. Biol. 69, 339-348.

Henrich, J. et al. (2005) “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav. Brain Sci. 28:795-815.

Henrich, J., et al. (2010). Markets, religion, community size, and the evolution of fairness and punishment. Science, 327(5972):1480-1484.

Ohtsuki, H. (2014). Evolutionary dynamics of n-player games played by relatives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 369, 20130359

Peña, J., Lehmann, L. & Nöldeke, G. (2014). Gains from switching and evolutionary stability in multi-player matrix games. Journal of Theoretical Biology 346:23-33.

Thöni, C. & Volk, S. (2018). Conditional cooperation: Review and refinement. Econ. Lett. 171, 37-40.

Van Cleve, J. (2015). Social evolution and genetic interactions in the short and long term, Theoretical Population Biology 103:2-26.