A Boolean approach to ecosystem structural uncertainty

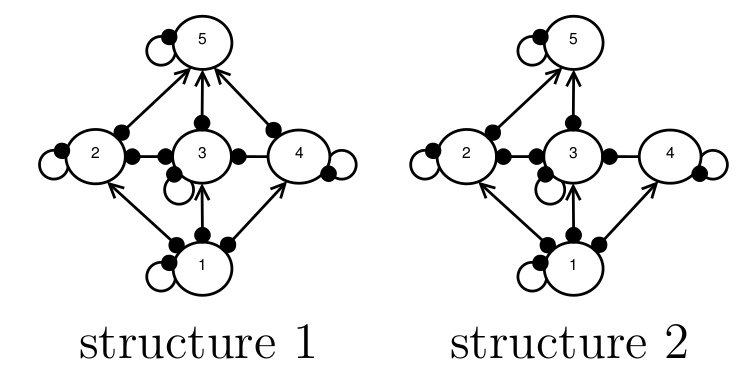

When conservation decision-makers attempt to predict the outcomes of management interventions, they frequently encounter uncertainty about the underlying ecosystem structure. Consider the example in Fig. 1, where experts are unsure whether species 4 and 5 interact. This uncertainty produces two possible structural configurations that could serve as model inputs.

How might we determine which structure more accurately reflects reality? Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) proposed a Bayesian method to address this type of structural uncertainty. However, as I will discuss in this blog post, their approach favours simpler structures over more complex ones. Simpler structures predict fewer possible species-response outcomes. Therefore, an important consequence of favouring simpler structures is that, when models based on them are used to predict the consequences of future management interventions, they will predict fewer possibilities, including precisely those negative unintended consequences that Qualitative Modelling aims to identify.

Figure 1. Two hypothetical ecosystem structures that might represent the true ecosystem. The four species are represented by nodes, the interactions between them by edges, positive interactions are represented by an arrow-head, and negative interactions by a filled dot.

The Melbourne-Thomas method

In summary, the Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) approach evaluates candidate structures by calculating their likelihood of reproducing observed ecosystem dynamics.

While their method could accommodate various types of observational data, the authors focused on species’ responses to press-perturbations. A press-perturbation is defined as an infinitesimally small, continuous removal or addition of species from a system (Bender et al., 1984; Yodzis, 1988; Nakajima, 1992). For example, consider Species 5 in Fig. 1 as a pest subject to a control programme removing 10 individuals weekly. This intervention constitutes a press-perturbation. Such a perturbation shifts the population equilibrium to a new steady-state. By comparing the population sizes before and during the pest-control programme, for example, researchers can use the directional changes observed (whether populations increased or decreased) as historical data points. It’s worth noting that this framework relies on ‘near-equilibrium assumptions’ (Abrams, 2001; Justus, 2006), including the assumption that populations achieved steady states both before and during perturbation, and the assumption that the perturbation was sufficiently small that its effects could by approximated by linearising the population dynamics around the steady states.

For the likelihood calculations, Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) used Monte Carlo simulations. They parameterised each candidate network structure by randomly sampling interaction strengths from a uniform distribution. They then simulated how a press-perturbation on one species (e.g., the pest species) would affect the population sizes of selected other species in the system. The likelihood assigned to each structure was simply the proportion of randomly parameterised models that correctly predicted the directional change (increase or decrease) in population sizes of the other species.

One of their simulation experiments

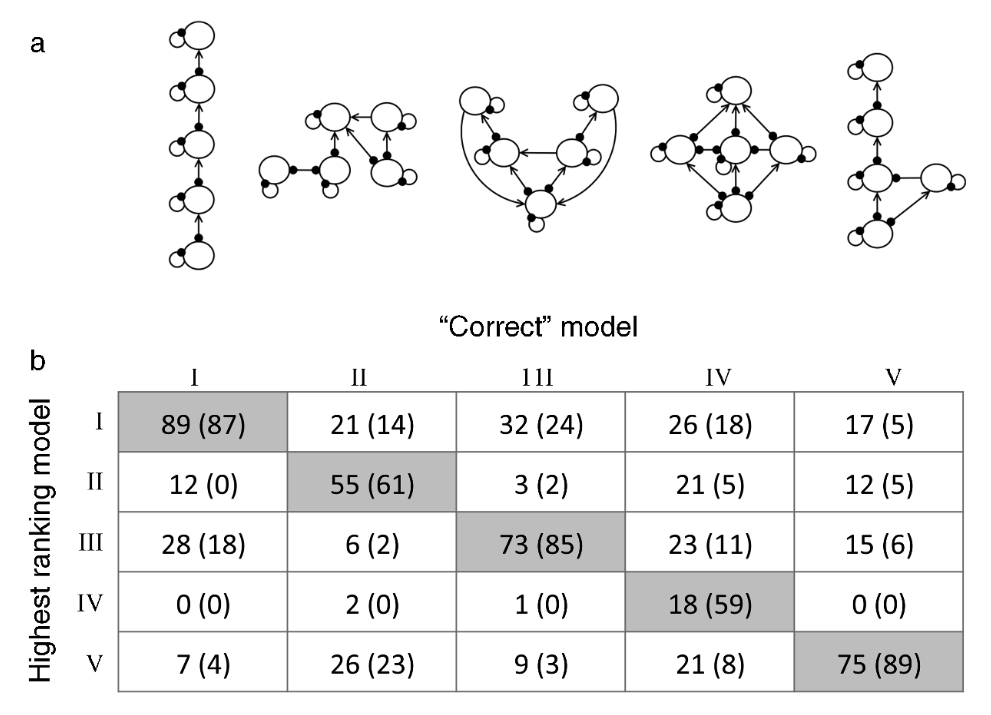

Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) evaluated their method using simulation experiments. Fig. 2 below reproduces the results from one such experiment (Fig. 5 from their manuscript), which assessed how successfully their approach identified the true network structure from among five candidates (Fig. 2a). For each trial, they designated one structure as the “correct” structure, randomly selected one species as the target for press-perturbation, and randomly chose two (or three) additional species to provide the response “observations”. Then they calculated likelihoods of all candidate structures as described above and determined the proportion of instances (\(P\)) in which each candidate structure (rows) achieved the highest likelihood for each correct structure (columns) (Fig 2b). In all scenarios except one (when Structure IV was the “correct” model), the candidate structure with the highest \(P\) value corresponded to the “correct” structure, leading the authors to conclude that their method performed well.

Figure 2. An evaluation of the Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) method, taken from Fig. 5 of their paper. (a) Five candidate network structures. (b) For each ‘correct’ target structure (columns), the frequency P with which each candidate structure (rows) had the highest likelihood. Values outside the parentheses are based on observations of two species’ responses, and values inside the parenthesis are based on three.

Preliminary observations

Before proceeding to my main point, I wish to make two observations about the approach and results above.

First, the candidate structures evaluated in the experiment above differ substantially from one another. In fact, they are drawn from markedly different systems (I: hypothetical generic food chain, II: tide-pool community, III: plankton community, IV: old-field food web, V: hypothetical structure). In contrast, uncertainty in real-world scenarios typically concerns the presence or absence of a small number of interactions. Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) did also evaluate their approach using real-world examples but using different methods. I found the method and results presented in Fig. 2 particularly easy to interpret. Therefore, in my simulation experiment below, I will use the same method to examine hypothetical structures but with more realistic levels of similarity.

Second, the use of Monte Carlo simulations — specifically, randomly sampling interaction strengths from a uniform distribution — invokes the probabilistic interpretation of the Principle of Indifference. I have written about this topic before (blog post, my paper in Methods in Ecology and Evolution); in short, this is an unsound way to represent ignorance of the interaction-strength magnitudes. Therefore, I will also investigate an alternative approach akin to the Boolean analysis I advocated for in my paper.

A thought experiment

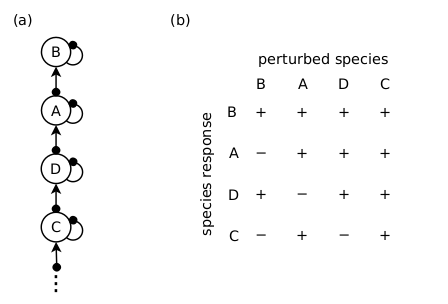

Consider a hypothetical scenario in which experts face maximal uncertainty about an ecosystem’s structure– any configuration might be possible. The system contains four species of interest: A, B, C, and D. From historical observations, a positive press-perturbation of Species A produces the following effects on population sizes:

- Species B: increase (\(+\))

- Species C: increase (\(+\))

- Species D: decrease (\(-\))

Because the signs of species’ responses to press-perturbations are entirely deterministic within a food chain (Usmani 1994; see also this blog post), modellers would assign the food chain structure depicted in Fig. 3a a likelihood of 1. Moreover, if they subsequently employed this structure within the Qualitative Modelling framework to forecast the consequences of a future management intervention, they would assign the highest certainty level — a probability of 1 — to all predictions, including erroneous ones.

Figure 3. (a) An ecosystem structure that reproduces the observed system behaviour (see text) with a likelihood of 1. (b) The matrix of the full behaviour predicted by structure (a). The observed behaviour is in the column headed ‘A’, and the model’s novel predictions to positive press-perturbations of the other species are in the other columns. All response signs hold true regardless of the parameter values, and therefore a Qualitative Modelling approach would assign every prediction a probability of 1.

While this hypothetical scenario admittedly stretches realism, it effectively illustrates why the Melbourne-Thomas approach is biased towards simpler network structures. The simulation experiment below will confirm this intuition.

Replication of the simulation experiment

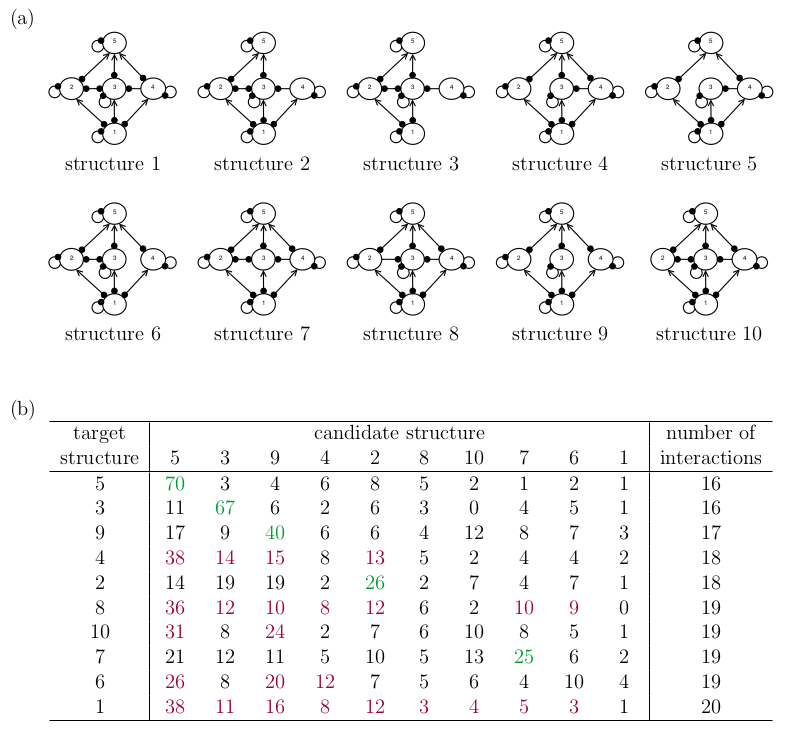

I conducted a fresh simulation experiment following the methodology of Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012), but applied it to the candidate structures illustrated in Fig. 4a. These structures represent variations of their original Structure IV with certain species interactions deliberately removed to create distinct candidates.

My selection of candidate structures was guided by two considerations. First, I designed the candidate structures to have high similarity to one another, thereby more accurately reflecting the nature of structural uncertainty typically encountered in real-world modelling scenarios. Second, I aimed to investigate how structural complexity influences the method’s performance. For this purpose, the number of interactions in each structure provides a rough but reasonably comparable metric of structural complexity across candidates.

Two key observations can be made from the tabulated results of the simulation experiment (Fig. 4b). First, the frequency with which the candidate structure with the highest \(P\) value corresponded to the “correct” structure declined from the 80% observed by Melbourne-Thomas et al. to 50% in this experiment.

Second, the \(P\) values for structurally simpler candidates when the target is complex (below the diagonal) are generally higher than the \(P\) values for structurally complex candidates when the target is simple (above the diagonal). The latter result confirms our intuition that the Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) method systematically favours simpler network structures.

Figure 4. A re-evaluation of the Melbourne-Thomas et al. (2012) method on more similar network structures. Note that the rows and columns in panel (b) are swapped from Fig. 2b. (a) Ten candidate network structures. (b) For each ‘correct’ target structure (rows), the frequency P with which each candidate structure (columns) had the highest likelihood. Cases where the ‘correct’ structure had the highest P are highlighted in green, and cases where another structure had higher P are highlighted in red. The final column counts the number of interactions in each target structure, which provides a rough measure of the target structure’s complexity.

Replication of the simulation experiment using a Boolean approach

The Boolean approach to Qualitative Modelling circumvents the challenges post by the Principle of Indifference by abandoning probabilistic interpretations entirely. Rather than working with probabilities and likelihoods, this approach classifies parameter values and outcomes using a straightforward three-valued logical system: (1) possible, (2) necessary, or (3) impossible.

To apply this three-valued system to structural uncertainty problems, I operate from a fundamental premise: if a species response pattern observed in the ‘correct’ structure is impossible within a candidate structure, then that candidate structure itself must be impossible. This perspective represents a significant shift in focus: instead of calculating how frequently a candidate structure can reproduce the ‘observed’ species responses across parameter space, we examine when a candidate structure cannot reproduce the observation regardless of the parameter values. This distinction also overcomes the inherent bias of the probabilistic approach towards simpler structures.

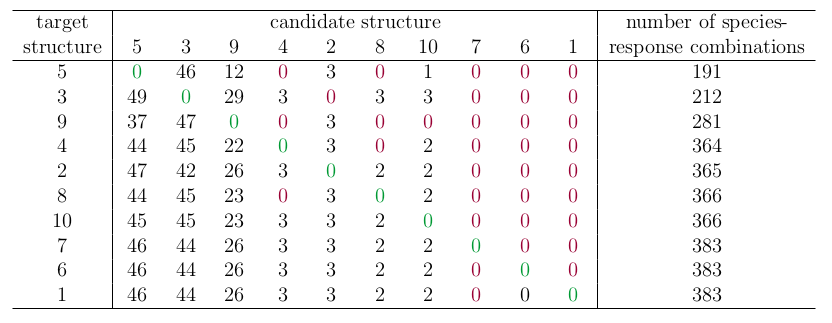

Fig. 5 tabulates the frequency \(Q\) with which each candidate structure is identified as impossible, and two key observations can be made. First, the method never favours an incorrect candidate structure over the ‘correct’ structure (i.e., all \(Q\) values on the diagonal of Fig. 5 are equal to zero). Second, the Boolean method favours more complex network structures, (i.e., lower \(Q\) values above the diagonal than below). In particular, it is often unable to exclude structurally complex candidate structures (i.e., columns of zeros on the right-hand side of Fig. 5). More complex structures also predict a greater number of possible species-response combinations.

Figure 5. An evaluation of a Boolean method for resolving structural uncertainty. The ten candidate and target structures are the same as shown in Fig. 4a. For each ‘correct’ target structure (rows), the frequency Q with which each candidate structure (columns) was excluded as impossible. Cases where the ‘correct’ structure was never excluded (Q=0) are highlighted in green, and cases where another structure had equal or lower Q are highlighted in red. The final column counts the number of species-response combinations that can be produced by each target structure, which measures the diversity of outcomes that can be predicted by models with that structure.

Discussion

The Melbourne-Thomas method favours simpler network structures. The thought experiment shows that a food-chain structure will always have the maximum likelihood. Although the thought experiment is contrived, it demonstrates that there is something paradoxical about using likelihood as the sole criterion to resolve structural uncertainty. This conclusion is reinforced by our replication of the simulation experiment where incorrect simpler structures were given a higher \(P\) score than several of the more complex structures (i.e. structures 1, 6, 8, 10) — a result attributable to the fact that the method disadvantages structurally-complex networks.

The tendency of the Melbourne-Thomas method to favour simpler structures may not be desirable from a conservation management perspective for both pragmatic and philosophical reasons. First, because selecting for simpler network structures leads to models that make less conservative predictions about the outcomes of future management interventions. Second, because the philosophical grounds for preferring simpler structures is unclear.

Because the likelihood measure favours simpler structures that produce fewer species-response combinations, it is favouring model structures that will foresee fewer possible outcomes to some proposed management intervention. Further, when those simpler structures are called upon to make predictions for conservation management within the Qualitative Modelling framework, the probability assigned to those predictions will be higher. For example, the simple chain structure can only predict one species-response combination– and it makes that prediction 100% of the time. However, another interpretation is that a food chain is too simple to predict alternatives. If the purpose of using Qualitative Modelling to support decision-making is a cautious one — to warn us about what might possibly go wrong when we interfere with ecosystems — then we should not favour models that warn us about fewer possible outcomes without a compelling reason to do so.

There is no obvious reason why real ecological systems might have a tendency to structure themselves to be simple. Nevertheless, one might argue that favouring structurally simpler networks is in accordance with the Principle of Parsimony. This is a philosophically complicated topic that I don’t have a clear understanding of. On one hand, we have examples of model-selection methods like AIC that can be interpreted as performing a trade-off between likelihood and model parsimony. Some authors interpret this as evidence that parsimony in and of itself is a valid principle. On the other hand, some authors say that AIC does not disfavour complex models because they are intrinsically less plausible but because they are over-fitted, and over-fitted models do a poor job of predicting future data. In the structural-uncertainty case, it seems that simpler structures are in fact the ones who are ‘over-fitted’ in the sense that the range of possible outcomes they can produce is constrained. Therefore, it seems that the notion of model complexity in terms of AIC (number of parameters) is not analogous to model complexity in terms of ecosystem structure. Perhaps the two perspectives can be reconciled if we interpret removing an interaction as akin to fixing a parameter value, i.e., setting the community-matrix element \(a_{i,j} = 0\)? I don’t know.

References

Bender, E. A., Case, T. J. and Gilpin, M. E. (1984). Perturbation experiments in community ecology: theory and practice, Ecology 65(1): 1–13.

Melbourne-Thomas, J., Wotherspoon, S., Raymond, B. and Constable, A. (2012). Comprehensive evaluation of model uncertainty in qualitative network analyses, Ecological Monographs 82(4): 505–519.

Nakajima, H. (1992). Sensitivity and stability of flow networks, Ecological Modelling 62(1): 123–133.

Usmani, R. A. (1994). Inversion of a tridiagonal Jacobi matrix, Linear Algebra and its Applications 212: 413–414.

Yodzis, P. (1988). The indeterminacy of ecological interactions as perceived through perturbation experiments, Ecology 69(2): 508–515.