Relationship between species discovery and extinction probability

[Update: thoughts in this post contributed to Kristensen et al. (2020).]

What is the relationship between a plant’s historical probability of having being discovered and its probability that it went extinct?

All else being equal, species with low abundance are less likely to be collected, and low abundance is both theoretically (e.g. McCarthy et al., 2014) and empirically cited as a good predictor of extinction probability. The empirical relationship has been observed both in general (McKinney, 1997) and specifically for plants (Sutton and Morgan, 2009; Matthies et al., 2004). It has also been found in the context of habitat fragmentation (Table 2 of Henle et al., 2004), which is particularly relevant to the tropics and development continues.

We can also expect size and range to mediate a negative relationship. Both small species (Sutton and Morgan, 2009; Marini et al., 2012) and species with restricted geographical ranges (e.g. Scheffers et al., 2012) are harder to detect and more vulnerable to habitat loss. On the other hand, collectors often have a bias towards novel specimens and rare finds (Guralnick and Van Cleve, 2005; Pyke and Ehrlich, 2010), which might ameliorate the relationships above to some unknown degree. Discoverability is also affected by higher level factors. For example, collections tend to be biased towards frequent-flowering species (fertile specimens are preferred) and accessible areas (Khoo et al., 2018).

Unevenness of habitat-type coverage is a particularly interesting factor, and it’s not obvious what generalisations can be made.

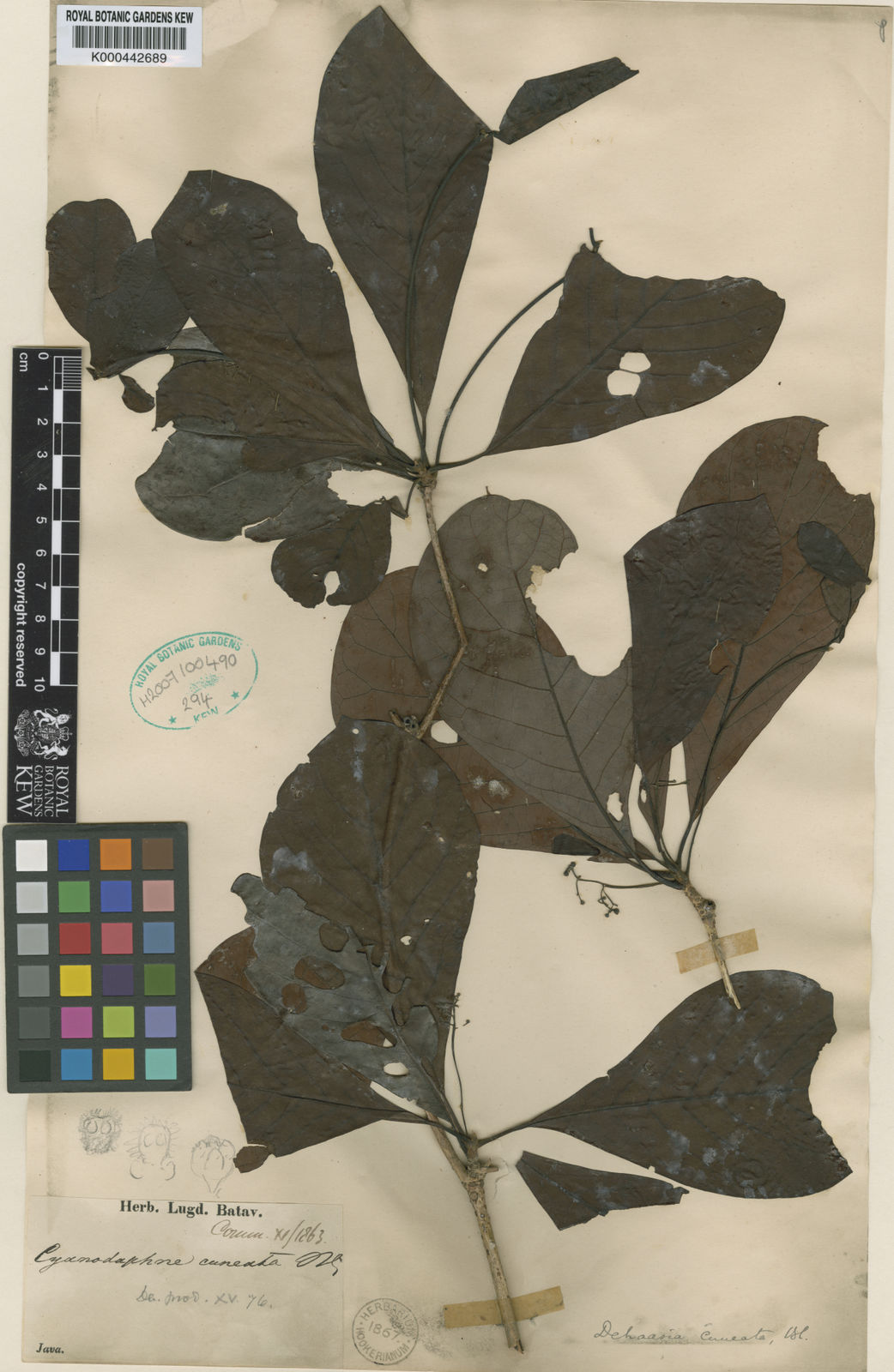

One tree newly discovered in Bukit Timah, Dehaasia cuneata. Photo credit: Specimen from Kew.

On one hand, inaccessible habitat may both lower the chance that a species is discovered and protect it from extinction. For example, 18 new species were recently discovered in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Singapore, which is situated on Singapore’s largest hill (Khoo et al., 2018). It’s worth emphasising that this reserve is not very large, and it is frequently visited by sight-seers and researchers alike. Nevertheless, the reserve does have some steep topography, and Khoo et al. (2018) attributed the length of time for which these individuals remained undiscovered to the inaccessibility of the area they were found. In general, many nature reserves are located in mountains and difficult areas. These areas were often ‘left over’ during development because they’re less desirable for human use.

On the other hand, less accessible habitat types may targetted for engineering to make them more useful to humans. This should increase the extinction probability for the undiscovered species living there. Swamp forests in Singapore have been highly impacted by inundation and reclamation, declining from approximately 5% (Corlett, 1992) to 0.39% today (Yee et al., 2011). Recently, 11 new and 53 rediscovered species have been found in remnant swamp (Chong et al., 2018). Chong et al. (2018) writes: “it is sobering to imagine what other biological treasures must have been lost when swamp forests such as those at Mandai and Jurong were inundated or reclaimed”.

The swamp-forest case study again highlights the idiosyncratic drivers of species discovery. Many of those rediscoveries were first discovered by a single collector, EJH Corner, in the 1930s, for whom the forests had become a “favourite haunt” (Corner, 1978). He writes about being “enthralled” by what he saw, tracts of forest “large enough for one to get lost”, even while describing the difficulties of working in the area. This was his particular passion, and he spent a decade visiting the sites.

‘Together we established a look-out in the canopy of the forest by driving iron-pegs into the trunk of a big Meliaceous tree (never identified) which served as a ladder, and I began to record leafing and flowering of surrounding trees and lianes until one day an incursion of minute ants bit me so insidiously that I cannot recall how I descended, got home, or retained sanity during hours of scalding irritation. After this I carried in my haversack a small bottle of Scrubb’s Ammonia which, by counter-irritation at least, rendered such bites tolerable.’ EJH Corner

The story, however, has a twist. During the time of Corner’s visits, extensive clearing was taking place, and this facilitated his access and discovery. For example, he describes finding recently felled trees lined up by the roads, which he used to identify otherwise difficult canopy species – creepers and epiphytes – as well as identifying the trees themselves.

I’m interested in the relationship between discovery and extinction probability because I want to know how to model it. At this point, I think it would be reasonable to assume that the relationship is negative; but beyond that, not much can be said without case-study specific expertise.

References:

Chong, K., Lim, R., Loh, J., Neo, L., Seah, W., Tan, S. and Tan, H. (2018). Rediscoveries, new records, and the floristic value of the Nee Soon freshwater swamp forest, Singapore, Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 70(Suppl 1): 49–69.

Corlett, R. T. (1992). The ecological transformation of Singapore, 1819-1990, Journal of Biogeography 19(4): 411–420.

Corner, E. (1978). Gardens’ Bulletin Supplment No. 1: The freshwater swamp-forest of south Johore and Singapore, Botanic Gardens Parks and Recreation Department Singapore.

Guralnick, R. and Van Cleve, J. (2005). Strengths and weaknesses of museum and national survey data sets for predicting regional species richness: comparative and combined approaches, Diversity and Distributions 11(4): 349–359.

Henle, K., Davies, K. F., Kleyer, M., Margules, C. and Settele, J. (2004). Predictors of species sensitivity to fragmentation, Biodiversity and Conservation 13(1): 207–251.

Khoo, M., Chua, S. and Lum, S. (2018). An annotated list of new records for Singapore: results from large-scale tree surveys at the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 70(1): 57–65.

Marini, L., Bruun, H. H., Heikkinen, R. K., Helm, A., Honnay, O., Krauss, J., Kühn, I., Lindborg, R., Pärtel, M. and Bommarco, R. (2012). Traits related to species persistence and dispersal explain changes in plant communities subjected to habitat loss, Diversity and Distributions 18(9): 898–908.

Matthies, D., Bräuer, I., Maibom, W. and Tscharntke, T. (2004). Population size and the risk of local extinction: empirical evidence from rare plants, Oikos 105(3): 481–488.

McCarthy, M. A., Moore, A. L., Krauss, J., Morgan, J. W. and Clements, C. F. (2014). Linking indices for biodiversity monitoring to extinction risk theory, Conservation Biology 28(6): 1575–1583.

McKinney, M. L. (1997). Extinction vulnerability and selectivity: combining ecological and paleontological views, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 28(1): 495–516.

Pyke, G. H. and Ehrlich, P. R. (2010). Biological collections and ecological/environmental research: a review, some observations and a look to the future, Biological Reviews 85(2): 247–266.

Scheffers, B. R., Joppa, L. N., Pimm, S. L. and Laurance, W. F. (2012). What we know and don’t know about Earth’s missing biodiversity, Trends in Ecology and Evolution 27(9): 501–510.

Sutton, F. M. and Morgan, J. W. (2009). Functional traits and prior abundance explain native plant extirpation in a fragmented woodland landscape, Journal of Ecology 97(4): 718–727.

Yee, A., Corlett, R. T., Liew, S., Tan, H. T. et al. (2011). The vegetation of Singapore – an updated map, Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 63(1&2): 205–212.