Modelling small insect dispersal

Background to the work

Bemisia tabaci biotype B, commonly known as silverleaf whitefly, is a sap feeding insect that has spread globally via trade in ornamental plants. It was first detected in Australia in 1994 (Gunning et al. 1995) and has since become a crop pest and an economic problem.

Eretmocerus hayati is a small parasitoid wasp that parasitises Bemisia tabaci by laying a single egg under the juveniles. Eretmocerus species have proved effective at controlling silverleaf whitefly in other countries (Goolsby et al. 2005), and so in 2004 the decision was made to release Eretmocerus hayati in Australia as a biocontrol measure against silverleaf whitefly.

Details about the species involved and the biocontrol program can be found in the publications of Paul De Barro. For my own part, the intentional introduction of biocontrol agents offers an excellent opportunity to model invasions and study invader dispersal.

The importance of spatial scale to model fitting

On 12 March 2005, a centre-point release of E. hayati was conducted in a field of green beans near Kalbar, Queensland. Over the remainder of the month, sampling was conducted on three spatial scales both to monitor the movement of the individuals released, and the parasitisations of silverleaf whitefly by the released parasitoids.

A hierarchical sampling design was used at three spatial scales: a local scale (tens of metres), a field scale (hundreds of metres), and the landscape scale (kilometres). Full details are in Kristensen et al. (2013a), but a brief description of the sampling is as follows.

On the local scale, beginning at 2 m from the release point, randomly chosen leaflets were turned over and adult parasitoids counted. This was repeated in each cardinal direction and for each subsequent 2 m, until three consecutive zeros at 2 m distances moving away from the release were recorded. On the field scale, a grid was determined over the field, and both direct counts of parasitoids were made on the grid, as well as counts of subsequent emergence from parasitised nymphs from leaves collected on the grid. On the landscape scale, at the end of the month, leaves were collected from the field and from sentinel fields across the landscape. Again, counts of emergence from parasitised nymphs on the leaves collected were made.

What we found was that the data from each spatial scale told a different story about the dispersal of the parasitoid (Kristensen et al. (2013a)). These “stories” were reflected in the different kinds of models that best suited the data at that scale.

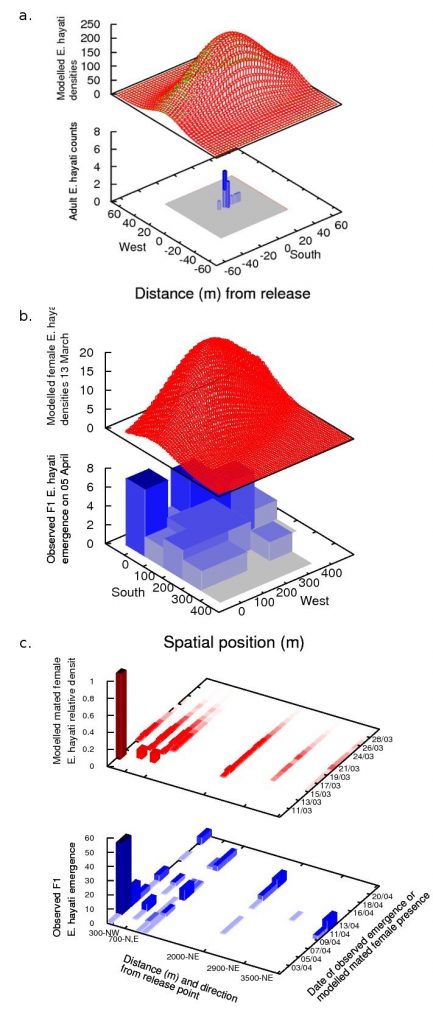

When the data at the local scale is considered alone (blue in adjacent figure a), it gives the impression that dispersal was confined to the tens-of-metres scale. This compares well with work by Simmons (2000), who reported that 95% of E. eremicus travelled 14.8 m or less over 8 days, and who successfully fitted a Gaussian redistribution kernel to the data. So a modeller presented with this data would likely employ a similar method, using a biased redistribution kernel to account for the east-west bias that is likely caused by the species’ phototactic response to the rising and setting of the sun. This gives the modelled densities in the red surface in the adjacent figure a.

The results at the field scale are considered, it suggests a quite different mode of parasitoid dispersal to the results on the local scale (adjacent blue, figure b). Parasitoids are no longer confined to dispersing within tens of metres, but disperse at least hundreds of metres, and with a north-westerly bias which coincides with the wind run. A modeller presented with this data would likely employ a Gaussian redistribution kernel similar to the local scale, but with a wind-advection component to account for wind-assisted dispersal, and fit a higher standard deviation of dispersal to account for the larger spread. However because the data we collected was course, fitting such a model would be very difficult without information from higher spatial scales. In our case, we used information from the landscape model (described below) to create the model (red surface, figure b).

Finally, the emergence data from the landscape scale demonstrates that mated females were able to disperse several kilometres from the release point, suggesting a wind-borne dispersal mechanism (blue, figure c). The data is also necessarily sparser than on smaller scales, and consequently cannot provide information about the diffusion-component of parasitoid dispersal. A modeller presented with this data would most likely attempt to fit a simple wind-advection model, where the dispersal of females was in the direction of the wind vector and proportional to the wind speed. We used a genetic algorithm to determine how to convert wind recordings into flight speeds, resulting in the model values shown in red in figure c.

In summary, using a single spatial scale to observe the spread of an invader can lead to a mistaken impression of the extent of the invader’s spread and a consequently erroneous interpretation of the species’ dominant dispersal mechanisms. Even when it appears that the spread of an invader is confined within the area searched, like in the local scale data, where the distribution has a characteristic tapering shape with tails confined well within the sampling area, this study shows that it is still possible for individuals to be found outside of that area. This can significantly change models and interpretation of the invader’s spread to one that moves further, faster, and by a different mechanism, which has obvious implications for both invasions and biological control. Consequently, we recommend that studies of the spread of an invader, particularly novel species, include some contingency sampling at multiple, larger spatial scales than the invader is expected to spread.

Model fitting and validation using a genetic algorithm

In addition to the Kalbar release described above, a second parasitoid release was conducted near Carnarvon, Western Australia. Again, the emergence of parasitoids from nymphs on leaves collected from sentinel sites was recorded. This data was then used to test the validity of the advection model fitted to the landscape scale data from the Kalbar release.

In order to create a dispersal kernel for an advection model, we had to determine the distance and direction that the mated female parasitoids would fly each day. The information we had available was the half-hourly wind-vector recordings that were made in the release field during the experiment, and the results of some flight-chamber experiments on related Eretmocerus species (Bellamy & Byrne 2001) showing that mated females will fly for an average of 10 min. The simplest way to use this was to say that the distance travelled each day was equal to the average flight time multiplied by the prevailing wind velocity multiplied by a scaling factor f:

flight distance = f × wind speed × flight time

In order to use the model as is, one must still make decisions about how to convert the half-hourly wind speed recordings into wind speeds to be applied to the wind-borne flights. For example, do we assume that female flights are evenly distributed throughout the day, or will they preference e.g. the morning or the afternoon? Will females fly at any wind speed, or will they delay their flights if the wind speed is too high because it might be dangerous?

Through a process of trial and error, it was found that the model performance was sensitive to three key conditions:

- The maximum wind-speed at which females would fly.

- The time of day at which flights occurred.

- The value of the scaling factor f. A genetic algorithm was used to fit the three parameters/conditions above, and the best fitting model was:

- Females will not fly if the wind speed is greater than 2.2 m/s.

- Wind-borne flights occur between 6.30 am and 5.30 pm.

- A scaling factor f = 1. This model may be contrasted with previous models fitted for Eretmocerus species in the literature, for which dispersal was dominated by diffusion processes, and parasitoid spread was constrained to the tens and hundreds of metres scales.

When the model fitted to the Kalbar data was applied to the Carnarvon release, it had mixed results. On one hand, the model did correctly predict an increase in parasitoid concentrations in the release field approximately 7 days after first emergence, which corresponded to days for which the wind velocities were above 2.2 m/s, preventing the parasitoids from flying. The model also correctly predicted the presence of parasitoids soon after the release in Fields 1600-W and 2300-W, which corresponded to that the late emergence in those fields from second-generation parasitoids. However, the predictions for NE Fields were poor.

The predictive performance of the Kalbar model can also be gauged by comparing it to the best-fitting model for the Carnarvon data:

- Wind-borne flights occur between 5.00 am and 7.00 pm.

- A scaling factor f = 2.02

The best-fitting Carnarvon model produces similar time-of-day ranges but doubles the scaling factor f. Nevertheless, when this model is applied to Kalbar data, it makes predictions that still retain key features from the Kalbar-fitted values, namely: the return of parasitoids to Fields 0, 300-NW and 700-NW after dispersal, and the general tendency for parasitoids to arrive at further fields later in the experiment.

To the specific question of E. hayati as an effective biocontrol agent for Bemisia, the results of this study are encouraging. Bemisia is known to travel on the wind for long times over long distances (Blackmer & Byrne 1993, Byrne et al. 1996), and so an effective biocontrol agent will need to have dispersal capabilities to match that. Evidence of wind-borne dispersal over several kilometres and suggests that E. hayati will be a more successful B. tabaci biocontrol agent than E. eremicus, the latter for which relatively poor dispersal capability has been cited as a key reason behind its failure as a biocontrol agent (Bellamy et al. 2004).

Model fitting and validation using Bayesian methods

In 2017, I teamed up with Christopher Strickland and Laura Miller, who were interested in seeing if a Bayesian fitting approach could improve the model (see Strickland et al. 2017). In contrast to the approach taken above, in the new model, diffusion processes were modelled on the landscape scale explicitly. Due to the coarseness of the data, the model that I had published was restricted to describing advection processes only. However, despite the fact that the data we had on the landscape scale was limited to sampling a few points hundreds of metres apart, the Bayesian approach was able to obtain reasonable estimates of parameters not only governing the advection processes but diffusion processes as well.

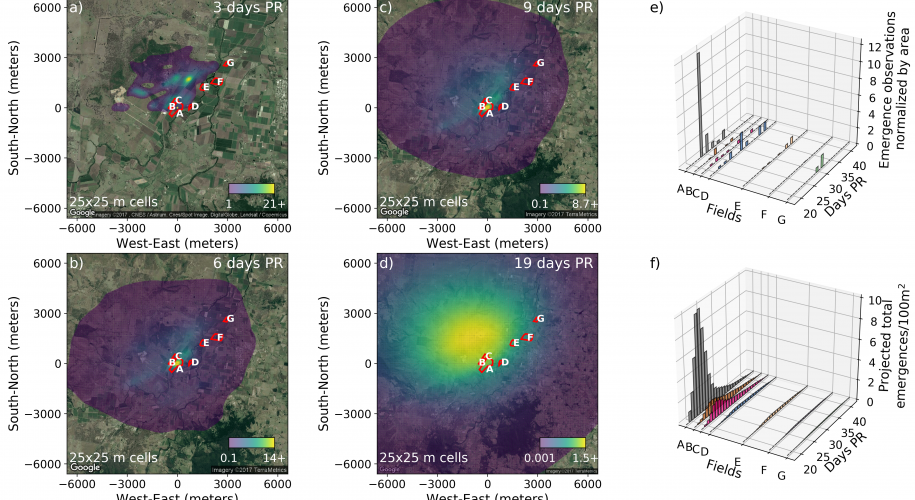

Results from the spatial model of parasitoids showing the expected mean number of individuals per 25x25 m cell (a) 3 days, (b) 6 days, (c) 9 days, and (d) 19 days post release, corresponding to data collection days. (e) Parasitoid emergence observation data per 100 sq-m (collection within rigorous sampling grid in the release field) and 10000 sq-m (sentinel fields). (f) model projected in-field emergences per 100 sq-m

The model fitted using Bayesian methods agreed with the previous method in that: a parameter relating take-off probability to wind speed was found to be useful, and the constant of proportionality relating wind speed to parasitoid drift was similar. The Bayesian result differed in that wasps were predicted to fly after sunset. We suspect that that these extended flight times reflect lack-of-fit to emergence data further away from the release site as described below.

Perhaps the most important result was that, again, there was an inability of the model to predict the relatively high densities of parasitoids at the farther fields. In order to explain the lack of fit, we are likely looking for some mechanism that would help concentrate parasitoids in crop fields that is missing from the model, either by preventing them from dispersing to surrounding native vegetation, and/or by attracting them to the crop fields themselves. One likely possibility is that parasitoids are using visual cues associated with host plants, and with the oncoming boundaries between crops and native vegetation, to trigger flight arrest and exit from the windstream. This is based on what we know about the biology of the species and the restrictions on what level of flight control is possible during wind-borne flight.

Parasitoids have available to them visual and olfactory cues indicative of potential hosts, but detecting these cues before take-off, in a way that is useful e.g. towards choosing a wind direction for long-distance dispersal, seems unlikely given the spatial scales in which they live. A parasitoid is unlikely to be able to see landscape-level cues before take-off. While there is plenty of evidence for olfactory cues being used for directed flight, this flight is local and against the wind (i.e. into the direction from which the chemical cue is coming), rather than long-distance and wind-borne. Therefore when insects enter the windstream for wind-borne flight, they cannot guarantee that they will move in an optimal direction, and so would not choose particular wind directions over others.

Once in the windstream however, they may be able to then use environmental cues to exit the windstream, which we discuss in the Methods section. Exit from the windstream is likely triggered by some combination of endogenous and visual cues. For example, for Eretomecerus specifically, flight chamber experiments show that they will respond to a plant-colour cue by settling, however flight arrest also appeared to have an endogenous flight-duration component, in that some wasps would not start responding to the cue before having flown for some considerable duration (Blackmer 2001). This raises the possibility that small insects in the windstream could respond to visual cues of host-plant presence, by exiting the windstream, before being carried past resources by the wind. Compton (2002 Dispersal Ecology) provides a good review of the general topic of cueing and control in long-distance wind-borne dispersal.

The possibility that the parasitoids might be able to control their wind-borne dispersal in this way is quite exciting. Wind-borne dispersal was historically thought of as a passive process, and early literature referred to wind-borne insects as ‘aerial plankton’ (Price, 1976 Environ. Entomol.). However it has been shown that insects modify their windborne flight by using behaviors that change their aerodynamic shape or by active flying, such as the selective timing of active flight used by aphids in response to the vertical direction of air currents (Reynolds and Reynolds 2009 Proc. R. Soc. B). For species that rely upon resources that have a patchy distribution at the landscape scale, wind-borne dispersal is a necessity, however an individual undertaking wind-borne flight runs the risk of being carried away from resource-rich areas altogether. Therefore we expect selection will act strongly on any possible strategies that arise that could reduce this risk. We suggest that visual cueing and selective flight arrest is a likely explanation, based upon the literature cited regarding phytophagous insects’ attraction to plant-related light wavelengths. We suggest this as a plausible ‘next step’ to modelling the parasitoids’ dispersal. However it is also possible that there is some other mechanism that we have not thought of, that could explain their ability to reach high densities in crop fields, and we indicate that this is a question needing further research.

Read the papers:

- Strickland, C., Kristensen, N.P., Miller, L. (2017) Inferring stratified parasitoid dispersal mechanisms and parameters from coarse data using mathematical and Bayesian methods, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 14(130): 20170005, (pdf)

- Kristensen, N.P., Schellhorn, N.A., and De Barro, P.J. (2013a) The initial dispersal and spread of an intentional invader at three spatial scales, PLoS One 8(5): e62407, (pdf)

- Kristensen, N.P., Schellhorn, N.A., Hulthen, A.D., Howie, L.J. and De Barro, P.J. (2013b) Wind-borne dispersal of a parasitoid: the process, the model, and its validation, Environmental Entomology, (pdf)

References:

Bellamy, D. & Byrne, D. (2001). Effects of gender and mating status on self-directed dispersal by the whitefly parasitoid Eretmocerus eremicus, Ecological Entomology 26: 571–577.

Bellamy, D., Asplen, M. & Byrne, D. (2004). Impact of Eretmocerus eremicus (Hymenoptera 17 : Aphelinidae) on open-field Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera : Aleyrodidae) populations, 18 Biological Control 29(2): 227–234.

Blackmer, J. & Byrne, D. (1993). Flight behaviour of Bemisia tabaci in a vertical flight chamber: effect of time of day, sex, age and host quality, Physiological Entomology 18: 223–232.

Byrne, D., Rathman, R., Orum, T. & Palumbo, J. (1996). Localized migration and dispersal by the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, Oecologia 105: 320–328.

Goolsby, J.A., De Barro, P.J., Kirk, A.A., Sutherst, R., Canas, L., Ciomperlik, M., Ellsworth, P., Gould, J., Hartley, D., Hoelmer, K.A., Naranjo, S.J., Rose, M., Roltsch, B., Ruiz, R., Pickett, C. & Vacek, D. (2005) Post-release evaluation of the biological control of Bemisia tabaci biotype “B” in the USA and the development of predictive tools to guide introductions for other countries. Biological Control 32: 70-77.

Gunning, R., Byrne, F., Conde, B., Connelly, M., Hergstrom, K. & Devonshire, A. (1995) First report of the B-biotype of Bemisia tabaci (homoptera, aleyrodidae) in Australia, Journal of the Australian Entomological Society 562 34 : 116–120.

Simmons, G. S. (2000). Studies on dispersal of a native parasitoid Eretmocerus eremicus and augmentative biological control of Bemisia tabaci infesting cotton, Ph. d. thesis, University of Arizon, Tucson.