Food web assembly algorithms

A food web assembly algorithm is a series of repeating steps by which a model food web can be created. Starting with one or a few species, new species are permitted to invade at each time step, and are lost at each time step, according to some prespecified rules. There is already a large body of food web assembly literature (Tregonning & Roberts 1979, Post & Pimm 1983, Mithen & Lawton 1986, Taylor 1988, Drake 1990, Law & Blackford 1992, Luh & Pimm 1993, Law & Morton 1996, Lockwood et al. 1997, Drossel et al. 2001, Bastolla et al. 2005, Virgo et al. 2006), and because assembly algorithms simulate invasion and extinction in a whole food web, they hold great promise for answering questions about succession, rehabilitation, and invasibility.

The rules governing which food webs survive intact to the next time step are often based on dynamical constraints, such as that the web must be locally stable or permanent. With the advent of faster computers, many more-recent assembly algorithms use numerical integration to determine which species persist through time.

Implicit in these algorithms are assumptions about how real food webs are structured. For example, algorithms that use stability as a constraint imply that real food webs are also constrained to be stable. Therefore, the validity of these theoretical assumptions can be tested by checking how well these algorithms perform in reproducing or making predictions about the structure of real food webs.

The structure of real food webs

What do real food webs look like?

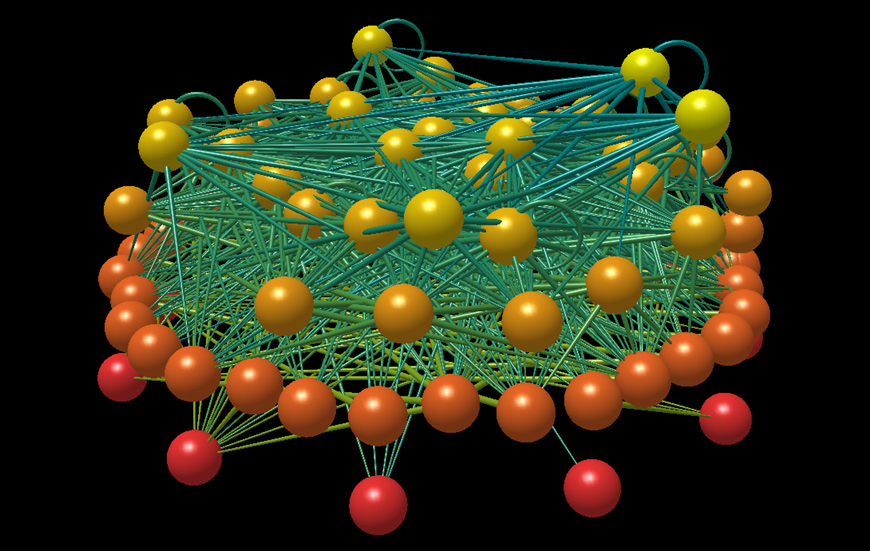

The Little Rock Lake food web. Image produced with FoodWeb3D, written by R.J. Williams and provided by the Pacific Ecoinformatics and Computational Ecology Lab (www.foodwebs.org, Yoon et al. 2004).

The figure adjacent shows the food web diagram for Little Rock Lake, a high-resolution food web described by Martinez (1991). It was recognised early on that food webs differ from random networks (Cohen & Newman, 1985), and there was been a mini-revolution in the quality of the empirical web catalogue since those earliest efforts (Paine, 1988; Martinez, 1991; Polis, 1991; Sugihara et al., 1997; Hall & Raffaelli, 1993; Winemiller & Polis, 1996). Subsequent to this, some static community models like the niche model (Williams & Martinez, 2000) and nested-hierarchy model (Cattin et al., 2004) were developed to provide a minimal set of rules that would do a reasonable job of reproducing the the properties of real webs.

These models are motivated by structure rather than dynamics. They use species richness and connectance as input parameters, in contrast to dynamical models, which typically have these parameters as outputs. For example, if one wanted to reproduce Little Rock Lake in the niche model, one would randomly assign the same number of species as in the real web to positions in the niche-hierarchy, and then use the connectance of the real web to determine how large a niche-range each species can predate upon. In contrast, in typical assembly models the feeding relationships are determined at random, and the end-result of how many and what types of species each predator feeds upon is determined by which of these randomly-generated species survive in the dynamics. So in assembly models, species richness and connectance are emergent properties. Nevertheless, static models represent the mark-to-beat for providing an adequate and parsimonious explanation for food web structure. Both the set of empirical webs they used for comparisons and the properties they measured have become the standard to which models are now compared (e.g. they were used in Loeuille & Loreau’s (2005) large-community evolution model).

How well do dynamical constraints like permanence fare at predicting real web structure?

In a paper to Am Nat, I tested the validity of permanence as a food web constraint by comparing real webs and static community webs (above) to the webs produced by three assembly algorithms: one constrained by permanence and feasibility, one by feasibility alone, and one with no dynamical constraint.

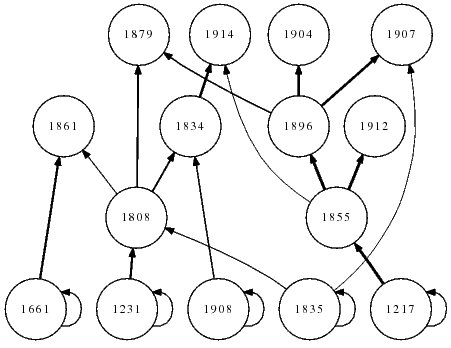

A permanent food web model produced by an assembly algorithm.

Surprisingly, other than the traditional measures of complexity related to species richness and web connectance, it has only been recently that studies (Bastolla et al., 2005; Neutel et al., 2007; Pawar, 2009a; Virgo et al., 2006) have compared detailed food web attributes resulting from assembly algorithms to real webs (see Pawar (2009b Thesis) for a review). Nevertheless, there is good external evidence that real webs are have structural attributes reflecting stability constraints, such as in their interaction-strength patterns (Yodzis, 1981; de Ruiter et al., 1995; Neutel et al., 2002).

The full results can be found in Kristensen (2008), however the short of it was that both of the dynamically-constrained algorithms did a poor job of reproducing the structure of real webs, and the addition of the permanence constraint onto the feasibility constraint did nothing to improve the comparison for the structural attributes chosen.

While it may seem a disappointing negative result, it is a useful result for two reasons. First, it provides a counter-weight to any potential “publication bias”, whereby the predictive successes of stability constraints are widely known, but the areas in which they fail are not. In contrast to these dynamical models, the static community models are very successful at predicting the structure of real food webs. This means that the physiological heuristics they are based on are the most parsimonious explanation we currently have for food web structure.

Second, given that there is good evidence that real webs are constrained by dynamics, it suggests that whatever the influence of dynamics web structure is, it may not be being picked-up by the empirical studies. We know, for example, that slight changes in food web topology can greatly change the stability of a web (Fox 2006). So while physiological constraints may be the best current explanation of web structure, this should be qualified by noting that what we know about food web structure may well be restricted to those aspects that are determined by physiological constraints to begin with.