Combining a stake in the future with the presence of others negatively affects intergenerational cooperation

Conservationists often urge us to think about what kind of world we want to leave to future generations. But what if thinking about future generations — and about our descendants, specifically — triggers a geneological self-interest in us that can cause the environmental message to backfire? That was one of the questions raised by Chia-chen Chang’s new paper in Royal Society Open Science.

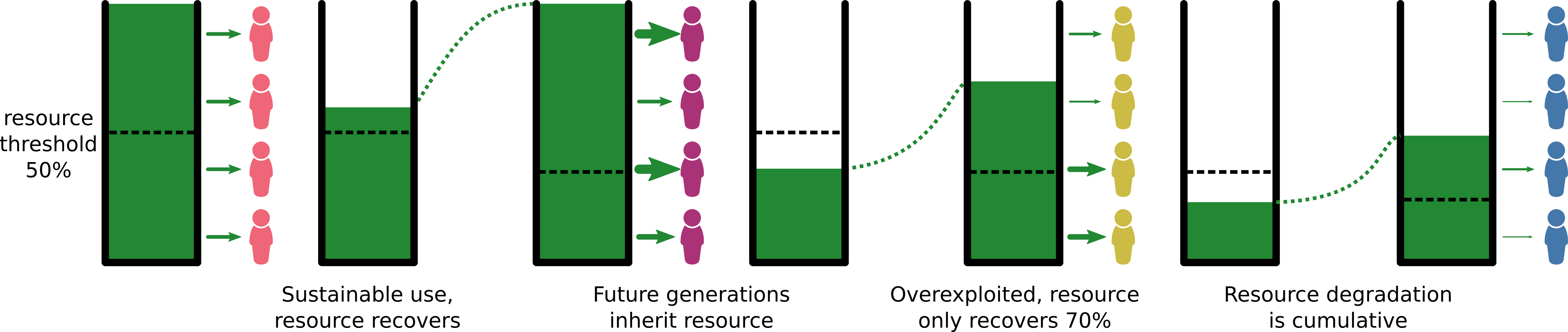

The paper concerns results from a lab-based intergenerational common-pool resource game (Fischer et al. 2004, Hauser et al. 2014, Lohse et al. 2020). A common-pool resource game is a game that is designed to mimic the behaviour of real-world natural resources, e.g., fisheries or forests, that can become degraded or destroyed if they are over-exploited. In our game, groups of experimental subjects were faced with an abstract resource from which they could harvest points, and for each point they individually harvested, they earned 50c. However, if the group harvested too many points (more than 50%), the resource would become degraded and less would be available to harvest next time.

Our game was also intergenerational, which means that the resource was passed on to a new group after each round. If the previous group over-exploited the resource, then there was less resource available for that next group to harvest. This creates a social dilemma: each player’s self-interest is at odds with the long-term collective interest. To sustain the resource, individuals need to limit their personal use, which means forgoing short-term rewards and potentially missing out if others do not do the same. Even more so, if the “next generation” are merely other strangers participating in the experiment, then there is little incentive not to act selfishly and extract the maximum amount possible. Therefore, this game provided us with a setting to explore the question: how can we motivate intergenerational cooperation?

Figure 1. An example of an intergenerational common-pool resource game.

We were interested in two main factors that might affect people’s motivations to act sustainably: the presence of others, and having a stake in the future of the pool. The presence of others may have positive or negative effects on sustainable behaviour. If others can perceive my environmental behaviour and will judge me for it, then that might motivate me to behave more sustainably (e.g., conspicuous green consumption) (Griskevicius et al. 2010, Jachimowicz et al. 2018). On the other hand, both theoretical models (Lehmann 2007) and empirical experiments (e.g., Suzuki & Akiyama, 2005, Wu et al. 2019) generally find that the larger a group is, the more difficult it is to sustain cooperation. Further, a field study found that urban residents depleted common-pool resources more quickly than rural residents (Timilsina et al. 2017).

To simulate an increased presence of others, we played a recording of background chatter. Such recordings of people-chatting sounds are known to invoke feelings of high population density (Sng et al. 2017). More importantly, although the experimental subjects knew these were recordings, we can still expect the feelings the recordings invoke to trigger behaviours suitable to a high-density environment without the complication of changing the structure of the game. Here, we take inspiration from Haley et al. (2005), who used a similar idea when exposing subjects to pictures of watching eyes. They write,

“given the substantial costs and benefits entailed by [distinctions between public and private situations], natural selection can be expected to have shaped human psychology to be exquisitely sensitive to cues that are (or were, under ancestral conditions) informative with respect to the likely profitability of cooperation in a given situation.”

Giving people a material stake in the future of a resource seems an obvious way to motivate sustainable behaviour. If I am likely to access the resource again, then that should incentivise me to act more sustainably. Another way to have a future stake is if one’s descendants are likely to use the same resource. If my own children are likely to inherit the resource, then I may be motivated to behave sustainably for their sake. This idea is supported by theoretical models; niche-construction models predict that natural selection can favour sustainable resource use if the resource is likely to be inherited by the users’ descendants (Lehmann 2007, Lehmann 2008). The idea is also supported empirically, e.g., families with children reduce their energy use more in response to health and environmental information than families without (Asensio et al. 2015).

However, conservation messaging focused on on caring for our children’s future has received some criticism (White 2017, Diprose et al. 2019). In short, telling people to behave sustainably for their descendants’ sake is still appealing to their selfishness, and this narrow scope of care does not match the scope of impact of modern environmental problems. White (2017) writes:

The implication of casting future people as kin groups is the thought that if individuals muster concern for their direct descendants then their moral responsibilities have been discharged. But what, one might ask, if an adequate response to the human costs of climate change demands that those in the world’s higher economic strata be mobilized to show concern for those to whom they are not directly related…? What if concern needs to be mustered for other people’s children, not just one’s own?

This is particularly important because an environmental message does not need to refer to an audience’s children specifically in order to trigger thoughts of one’s family; any reference to “future generations” can have the same effect. From in-depth interviews with urban residents in both the UK and China, Diprose et al. (2019) observed:

When we asked broad questions such as ‘Do people alive today have responsibility for future generations?’ or ‘What kind of responsibility do you think people have to future generations?’, the majority of interviewees in both Sheffield and Nanjing responded by talking about their responsibility for family members. This was the case even when we added prompts such as ‘say, 50 years later’ or ‘100 years from now’.

Diprose et al. (2019) echo White’s (2017) assessment:

Whilst considering how climate change will affect ‘our children’ provides a relatable perspective on a complex and seemingly distant global problem, it does so by appealing to self-interest and the preservation of genealogy. Our research suggests that this framing tends to narrow the scope of intergenerational concern to more immediate worries like whether people’s children will have financial and social security and be good citizens.

The messaging problem becomes even more pronounced the greater the number of people accessing the shared resource. Returning to the theoretical models above, although they predict that having a geneological stake in the future of the pool can favour sustainable resource use, the effect becomes more difficult to achieve the larger the number of individuals sharing the resource pool becomes (Eq. SI A.15). If this evolutionary mechanism did indeed help shape human psychology with respect to sustainability, then might natural selection have also shaped us to respond unfavourably if the group size is large?

In our study, to simulate a stake in the future of the pool, participants were told that there was a 50% chance that they would inherit the pool in the next generation of the game. This may be interpreted as a chance to use the resource again later in life, but it also represents a very literal interpretation of the genealogical mechanism discussed above, i.e., parents and their biological children have a relatedness coefficient of 50%.

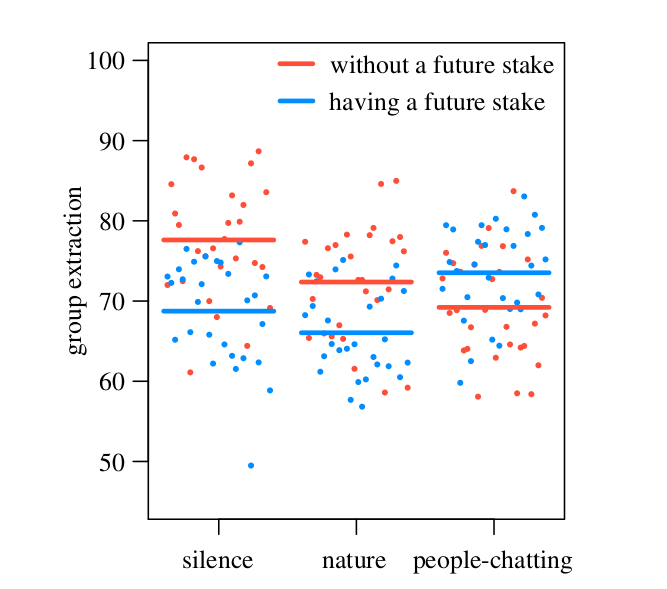

As we expected, having a future stake decreased the amount of resource extracted, both in the silence and nature-sounds treatment. This matched our expectation that, if there is a chance that you will be using the same pool in the next round, then it’s in your interests for that resource to be sustained.

However, when experimental subjects were exposed to the people-chatting sounds, having a stake in the future of the pool increased extraction. This was true in a one-shot game (Fig. 2), and a similar negative interaction was also observed in a dynamic game.

Figure 2. Having a stake in the future of the resource pool (blue) decreases the amount extracted (compared to red) except when participants were exposed to the people-chatting sound treatment.

Why would having a future stake promote sustainability in the first two sound treatments but have the opposite effect under people-chatting sound-treatment? We hypothesise that the reason this occurred is because reminders of the presence of others triggers a behavioural response suitable to a larger group of people sharing a resource pool. As discussed above, both theory and experiments find that a shared resource will become harder to sustain the larger the number of people sharing it. Although the lab participants know that their group size is 5 individuals, the process of human decision-making involves not just propositional knowledge but also an intuitive judgement process (Haley et al. 2005). The sense that there are many people around causes people to behave as though there really are many people around, including more people accessing the shared resource.

Introducing a material future stake also seems to have “crowded out” non-material motivations. Crowding-out is the phenomenon where financial incentives for cooperative behaviour can backfire and cause people to behave less cooperatively than before (Bowles 2016). When the people-chatting sound treatment was used alone, with no future stake, it decreased extraction compared to silence. We expected this result because reminders of the presence of others can trigger reputational concerns (above) and strengthen the normative behaviour. We also expect this to be robust to factors that threaten the actual sustainability of the resource — including the intuitive perception that more people are accessing the resource — because moral judgement is often deontological (Everett et al. 2016) and places higher importance on intentions than utilitarian efficacy. Therefore, an individual can receive the non-material “payoff” of sustainable behaviour whether or not that individual actually made much difference to the future of the resource pool. In contrast, if a person’s focus is shifted away from such non-material payoffs to future material ones, then the payoff very much depends on whether or not the pool is likely to be sustained. If it is unlikely to be sustained regardless of what that individual does, then it makes sense to maximise extraction now so one doesn’t miss out altogether.

It is interesting to note that nature sounds also decreased extraction (marginally) compared to silence sound-treatment. Previous work has found that exposure to nature has positive effects on cooperative and sustainable behaviour (e.g., Piff et al. 2015, Zelenski et al. 2015, Joye et al. 2020).

Obviously, more work is needed before we can relate our results directly to environmental messaging about “future generations”. While our treatment, with a 50% chance to inherit the pool in the next generation, is mathematically equivalent to the 50% genetic relatedness between a parent and offspring in theoretical models, it is unlikely that our experiment captured the true psychology of kinship. It would be interesting to test these ideas directly using real parent-child dyads. Nevertheless, if the negative interaction we observed between reminders of the presence of others and future stakes can be generalised, then this has important implications for environmental messaging.

Our result raises the possibility that environmental messaging that (inadvertently) triggers the audience’s geneological self-interest by invoking “future generations” may backfire, particularly in large-scale environmental problems like climate change. If individuals feel the scale of cooperation required to solve the problem is too large, and the resource is unlikely to be sustained anyway, then their best strategy — from a geneological perspective — is to maximise extraction now and pass on economic benefits to their descendants instead.

Read more

References

Asensio OI, Delmas MA. 2015 Nonprice incentives and energy conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 510–515. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1401880112)

Bowles S. 2016 The moral economy: why good incentives are no substitute for good citizens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Diprose K, Liu C, Valentine G, Vanderbeck RM, McQuaid K. 2019 Caring for the future: climate change and intergenerational responsibility in China and the UK. Geoforum 105, 158–167. (doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.019)

Everett JA, Pizarro DA, Crockett MJ. 2016 Inference of trustworthiness from intuitive moral judgments. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 772–787. (doi:10.1037/xge0000165)

Fischer M-E, Irlenbusch B, Sadrieh A. 2004 An intergenerational common pool resource experiment. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 48, 811–836. (doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2003.12.002)

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Van den Bergh B. 2010 Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 392–404. (doi:10.1037/a0017346)

Haley KJ, Fessler DM. 2005 Nobody’s watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 26, 245–256. (doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.01.002)

Hauser OP, Rand DG, Peysakhovich A, Nowak MA. 2014 Cooperating with the future. Nature 511, 220–223. (doi:10.1038/nature13530)

Jachimowicz JM, Hauser OP, O’Brien JD, Sherman E, Galinsky AD. 2018 The critical role of second-order normative beliefs in predicting energy conservation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 757–764. (doi:10.1038/s41562-018- 0434-0)

Joye Y, Bolderdijk JW, Köster MA, Piff PK. 2020 A diminishment of desire: exposure to nature relative to urban environments dampens materialism. Urban For. Urban Green 54, 126783. (doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126783)

Lehmann L. 2007 The evolution of transgenerational altruism: kin selection meets niche construction. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 181–189. (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01202.x)

Lehmann L. 2008 The adaptive dynamics of niche constructing traits in spatially subdivided populations: evolving posthumous extended phenotypes. Evolution 62, 549–566. (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00291.x)

Lohse J, Waichman I. 2020 The effects of contemporaneous peer punishment on cooperation with the future. Nat. Commun. 11, 1815. (doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15661-7)

Piff PK, Dietze P, Feinberg M, Stancato DM, Keltner D. 2015 Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 883. (doi:10.1037/pspi0000018)

Sng O, Neuberg SL, Varnum ME, Kenrick DT. 2017 The crowded life is a slow life: population density and life history strategy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 112, 736–754. (doi:10.1037/pspi0000086)

Suzuki S, Akiyama E. 2005 Reputation and the evolution of cooperation in sizable groups. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 1373–1377. (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3072)

Timilsina RR, Kotani K, Kamijo Y. 2017 Sustainability of common pool resources. PLoS ONE 12, e0170981. (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170981)

White J. 2017 Climate change and the generational timescape. Sociol. Rev. 65, 763–778. (doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12397)

Wu J, Balliet D, Peperkoorn LS, Romano A, Van Lange PAM. 2019 Cooperation in groups of different sizes: the effects of punishment and reputation-based partner choice. Front. Psychol. 10, 2956. (doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02956)

Zelenski JM, Dopko RL, Capaldi CA. 2015 Cooperation is in our nature: nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 42, 24–31. (doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.005)