Intergenerational reciprocity and restoration

In conservation, we often talk about intergenerational equity, which is the idea that we should behave sustainably out of fairness towards future generations. However, how we treat others often depends on how we have been treated ourselves. If previous generations have over-exploited the natural resources and behaved unsustainably, will that make us feel less inclined to behave sustainably for future generations? In Chia-chen Chang’s recent paper in Sustainability Science, we explored this question using an experimental common-pool resource game.

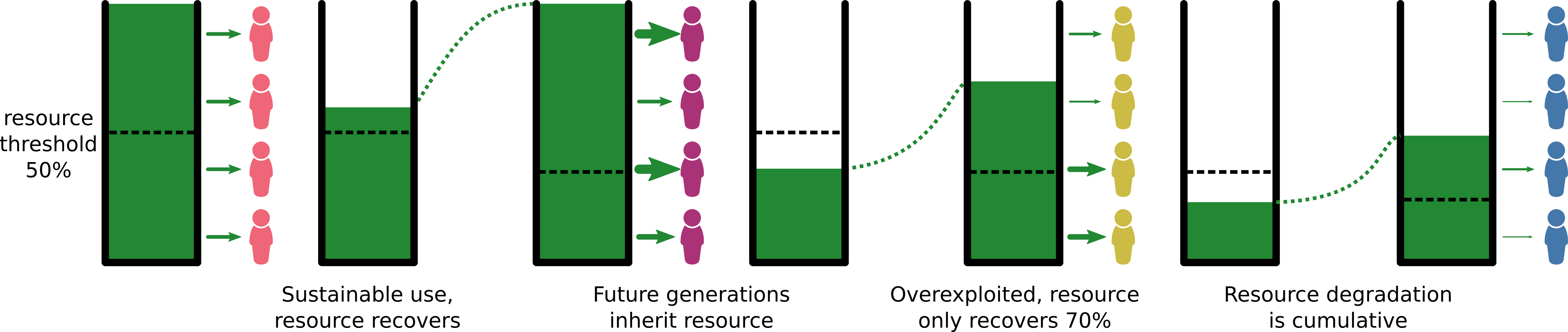

An example of a common-pool resource game

The paper is specifically interested in restoration, and the key innovation was to investigate both extraction and restoration decisions together in the experimental game. Deforestation is a key factor contributing to both climate change and biodiversity loss (Barlow et al. 2016; Laurance and Williamson 2001; Lawrence and Vandecar 2015), and forest restoration is one significant intervention that we could use to ameliorate these effects (Clewell and Aronson 2013; Hanberry et al. 2015; Suding et al. 2015). Intergenerational cooperation has been studied before using experimental common-pool resource games (Fischer et al. 2004); for example, finding that voting or peer punishment can reduce resource extraction or increase contribution to a common-pool resource (Hauser et al. 2014; Lohse and Waichman 2020). However, restoration has not been investigated before using an intergenerational common-pool resource game.

Previous work suggests that the behaviour of future generations will affect both extraction and restoration in the current generation (Wade-Benzoni 2002). When an individual perceives that the previous generation passed on benefits (or burdens) to the current generation, then they also tended to pass on benefits (or burdens) to the next generation (Wade-Benzoni 2002, 2019). Therefore, we predicted that, if previous generations in the game failed to sustain the resource pool, then individuals would extract more from the pool, contribute less to restoration, and the pool would be less likely to be sustained.

We were also interested in the role of emotions and cognitive style. Emotions are often a proximate mechanism linking a situation and an individual’s response; therefore, we expected emotions to be linked to in-game behaviour. For example, guilt is an emotion that motivates repair (Ferguson and Branscombe 2010; Harth et al. 2013; Schneider et al. 2017; Skatova et al. 2017), therefore we might expect it to motivate restoration of damaged ecosystems. However, an individual’s behaviour in a social dilemma also depends upon the cognitive style they use to arrive at their decision, i.e., whether they use a faster and more intuitive “go with your gut” process, or if they take a more deliberative approach (Rand 2016). Because the common-pool resource game is a social dilemma, the “rational” strategy to maximise one’s payoff is to extract as much as possible and contribute nothing to restoration. Therefore, we would expect individuals who tend to use a more deliberate thinking process to extract more and contribute less to restoration.

Results

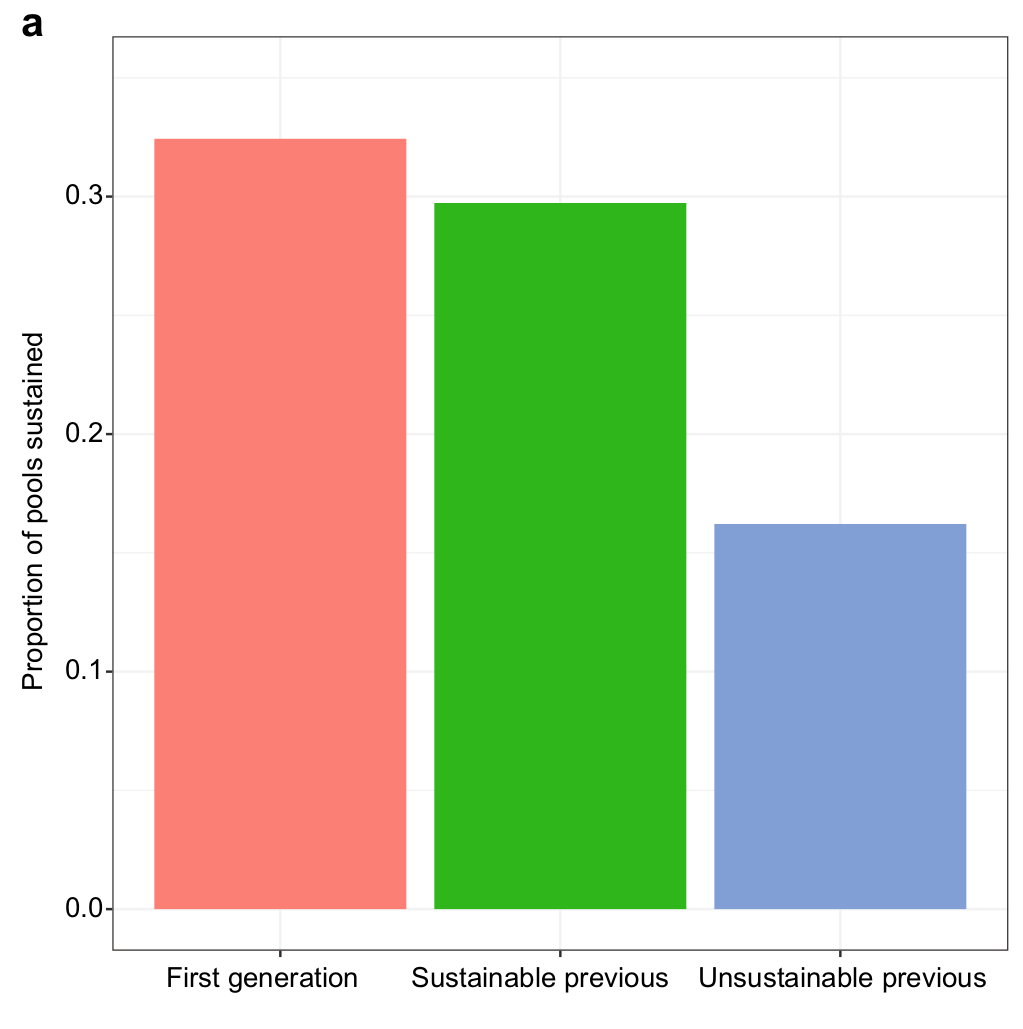

The key finding was that restoration could rescue pools from over-exploitation; however, the proportion of pools sustained decreased by approximately 50% when groups had unsustainable previous generations. This finding was consistent with our expectations and the intergenerational reciprocity hypothesis (Wade-Benzoni 2002). It suggests that the failures of previous generations can undermine the willingness of the current generation to behave sustainably, and unsustainable behaviours in current generations may have perpetuating effects that will reinforce environmental degradation in future generations.

The proportion of pools sustained in each generation treatment.

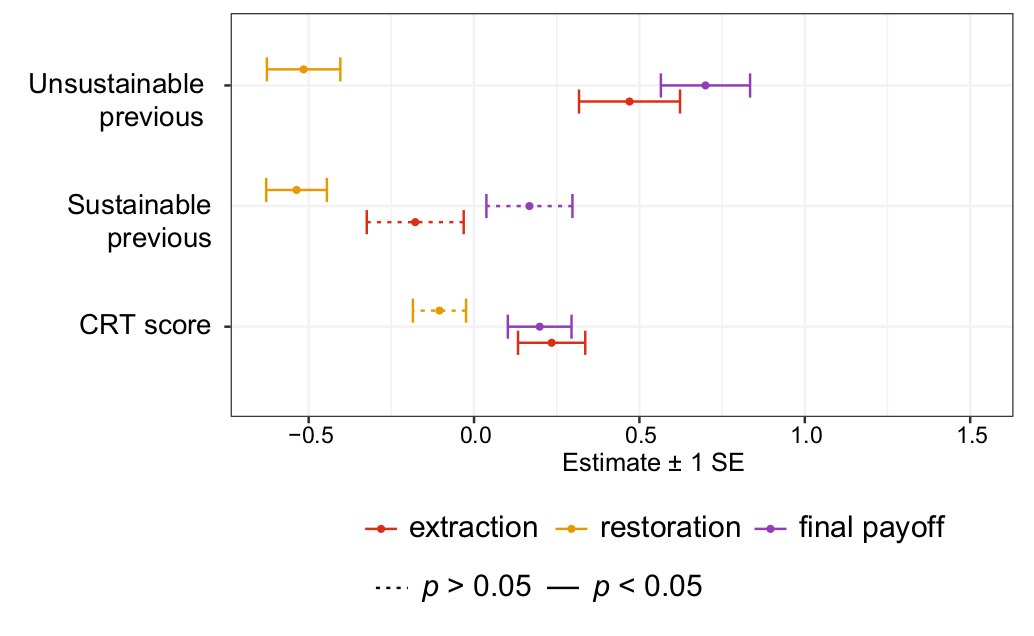

Consistent with our expectations, if previous generations behaved unsustainably, then the current generation extracted more resources; however, contrary to our expectations, we did not detect an effect of previous generations’ behaviour on restoration decisions. We had a similarly mixed result in the relationship between cognitive style and extraction vs. restoration decisions. As expected, we found that intuitive thinkers extracted less resource; however, we did not find evidence of a relationship between an individual’s cognitive style and their restoration decisions. One possible explanation for the difference between extraction and restoration may involve loss aversion. Loss aversion is the stronger preference to avoid losses than to obtain equivalent gains (Kahneman et al. 1991). Therefore, people may tend to avoid returning resource points after extraction but be more willing to extract fewer resource points in the first place.

Summaries of three models with individual extraction behaviour, restoration behaviour, and final payoff as response variables. Unsustainable previous and sustainable previous generations were compared against the first generation.

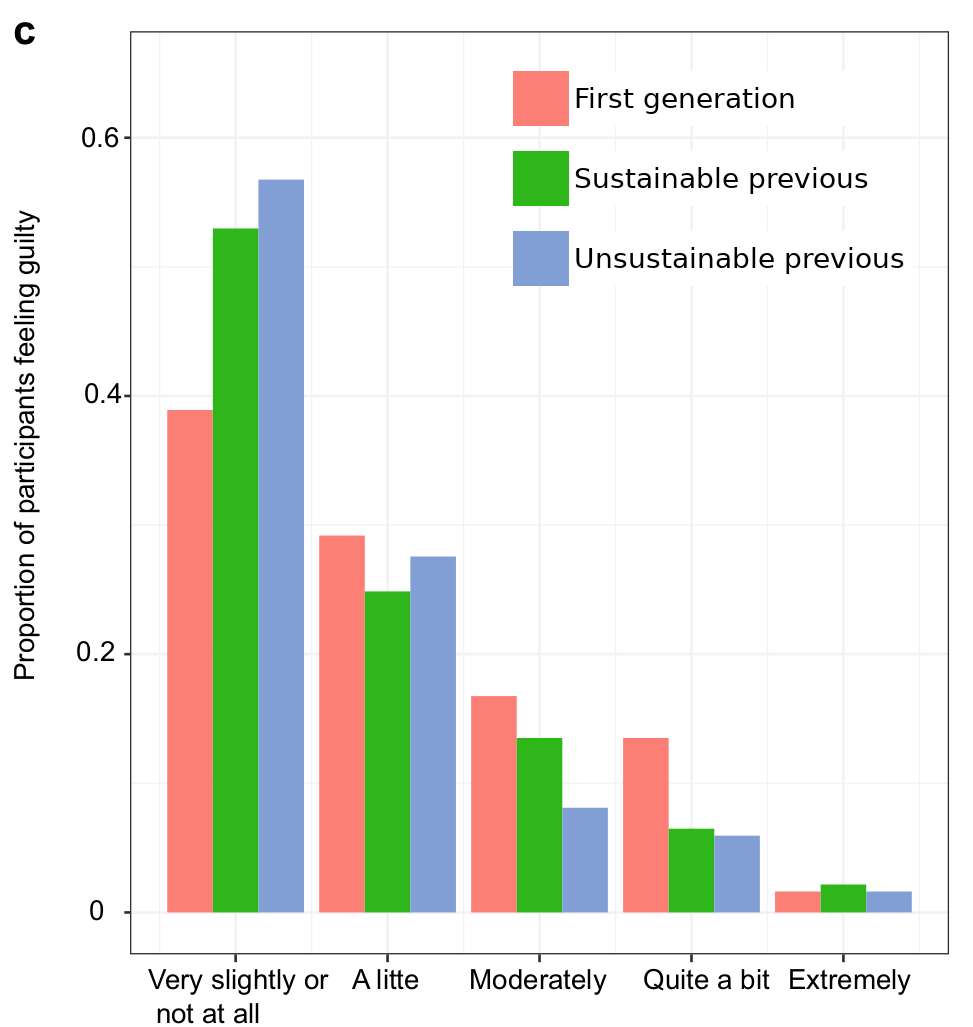

Both guilt and anger had a positive relationship with an individual’s contribution to restoration, and when individuals were in the first generation, they felt guiltier at the end of the resource extraction (all groups over-exploited) and contributed more to restoration. These results are broadly consistent with previous studies: guilt promotes repair (Ferguson and Branscombe 2010; Harth et al. 2013; Skatova et al. 2017); people who care for the future of ecosystems feel angrier about climate change (Cunsolo and Ellis 2018; Wang et al. 2018); anger can motivate altruistic behaviour e.g., to pay additional costs to punish non-cooperators (Fehr and Gachter 2002; Rodrigues et al. 2018); and being in a position of power over others, as the first generation was over all subsequent generations, induces greater feelings of social responsibility (Tost and Johnson 2019; Tost et al. 2015; Wade-Benzoni 2019; Wade-Benzoni et al., 2008).

The proportion of participants reporting feeling guilty at the end of resource extraction. Note that all groups over-exploited the resource. Guiltier-feeling also individuals contributed more to restoration.

Read more

The paper is available in early view here, or try the permanent link: Chang, Cc., Kristensen, N.P., Nghiem, T.P.L., Tan, C.L.Y., Carrasco, L.R. (2021) Cooperating with the future through natural resources restoration, Sustainability Science, In press

References

Barlow J, Lennox GD, Ferreira J, Berenguer E, Lees AC, MacNally R et al (2016) Anthropogenic disturbance in tropical forests can double biodiversity loss from deforestation. Nature 535:144–147

Clewell A, Aronson J (2013) The SER primer and climate change. Ecol Manag Restor 14:182–186

Cunsolo A, Ellis NR (2018) Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Chang 8:275

Fehr E, Gachter S (2002) Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415:137–140

Ferguson MA, Branscombe NR (2010) Collective guilt mediates the effect of beliefs about global warming on willingness to engage in mitigation behavior. J Environ Psychol 30:135–142

Fischer M-E, Irlenbusch B, Sadrieh A (2004) An intergenerational common pool resource experiment. J Environ Econ Manag 48:811–836

Hanberry BB, Noss RF, Safford HD, Allison SK, Dey DC (2015) Restoration is preparation for the future. J Forest 113:425–429

Harth NS, Leach CW, Kessler T (2013) Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behaviour: different emotions predict distinct intentions. J Environ Psychol 34:18–26

Hauser OP, Rand DG, Peysakhovich A, Nowak MA (2014) Cooperating with the future. Nature 511:220–223

Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH (1991) Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5:193–206

Laurance WF, Williamson GB (2001) Positive feedbacks among forest fragmentation, drought, and climate change in the Amazon. Conserv Biol 15:1529–1535

Lawrence D, Vandecar K (2015) Effects of tropical deforestation on climate and agriculture. Nat Clim Chang 5:27–36

Lohse J, Waichman I (2020) The effects of contemporaneous peer punishment on cooperation with the future. Nat Commun 11:1815.

Rand DG (2016) Cooperation, fast and slow: Meta-analytic evidence for a theory of social heuristics and self-interested deliberation. Psychol Sci 27:1192–1206

Rodrigues J, Nagowski N, Mussel P, Hewig J (2018) Altruistic punishment is connected to trait anger, not trait altruism, if compensation is available. Heliyon 4:e00962

Schneider CR, Zaval L, Weber EU, Markowitz EM (2017) The influence of anticipated pride and guilt on pro-environmental decision making. PLoS ONE 12:e0188781

Skatova A, Spence A, Leygue C, Ferguson E (2017) Guilty repair sustains cooperation, angry retaliation destroys it. Sci Rep 7:46709

Suding K, Higgs E, Palmer M, Callicott JB, Anderson CB, Baker M et al (2015) Committing to ecological restoration. Science 348:638–640

Tost LP, Johnson HH (2019) The prosocial side of power: how structural power over subordinates can promote social responsibility. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 152:25–46

Tost LP, Wade-Benzoni KA, Johnson HH (2015) Noblesse oblige emerges (with time): power enhances intergenerational beneficence. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 128:61–73

Wade-Benzoni KA (2002) A golden rule over time: reciprocity in intergenerational allocation decisions. Acad Manag J 45:1011-1028

Wade-Benzoni KA (2019) Legacy motivations & the psychology of intergenerational decisions. Curr Opin Psychol 26:19–22

Wade-Benzoni KA, Hernandez M, Medvec V, Messick D (2008) In fairness to future generations: the role of egocentrism, uncertainty, power, and stewardship in judgements of intergenerational allocations. J Exp Soc Psychol 44:233–245

Wade-Benzoni KA, Tost LP (2009) The egoism and altruism of intergenerational behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 13:165–193

Wang S, Leviston Z, Hurlstone M, Lawrence C, Walker I (2018) Emotions predict policy support: why it matters how people feel about climate change. Glob Environ Chang 50:25–40