Using n-player relatedness to model the Modern Tragedy of the Commons

In this blog post, I will use the “Modern Tragedy of the Commons” as an example for how to use Hisashi Ohtsuki’s \(n\)-player generalisation of relatedness.

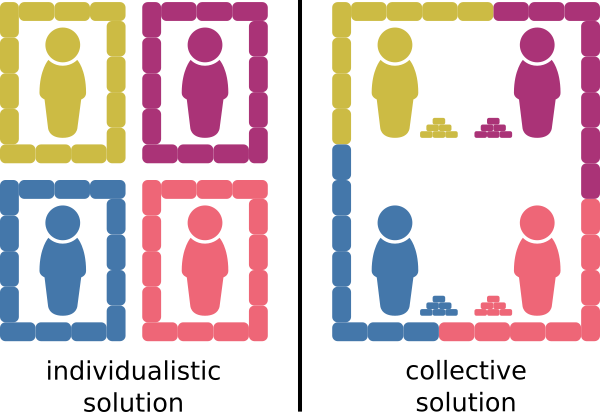

In a recent experimental study in Science Advances, Gross and De Dreu (2019) described the Modern Tragedy of the Commons: if people can individually solve a problem by purchasing a solution that protects themselves only, then they may prefer that to contributing to a cheaper collective solution (Fig. 1). One recent example might be the trend among wealthy Californian home-owners to hire private firefighters to defend their property from wildfires exacerbated by climate change. Gross and De Dreu (2019) argued that the Modern Tragedy of the Commons is particularly important because recent global economic changes have given rise to an increasingly individualistic mind-set and environmental degradation has created markets for products to ameliorate its effects.

Figure 1: The Modern Tragedy of the Commons. Four individuals must build a protective wall. To simplify matters, they have only two strategies available to them. They may (1) spend bricks to build a wall that protects themselves only, or (2) contribute bricks towards a collective wall that protects the whole group. The collective solution costs fewer bricks per person and is the most efficient way to allocate resources; however, the individualistic solution is guaranteed to succeed regardless of what the other individuals choose to do.

The Modern Tragedy of the Commons can be formalised as a public goods game with a threshold effect. Let \(a_k\) and \(b_k\) denote the payoff to the collectivist and individualist, respectively, given that \(k\) of the other members of the group are collectivists. I’ll rescale the problem so that the individualistic solution is the default, setting \(b_k = 0\) constant. Let \(C\) be the cost of failure (e.g. an incomplete protective wall in the figure above), and let \(B-C\) be the saving made by pursuing a successful collective solution (e.g. the leftover bricks). Let’s consider the case where the collective solution requires all 4 group members to be collectivists. Then the collectivist payoffs are:

\[[a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3] = [-C, -C, -C, B-C] \tag{1} \label{1}\]The fact that this 4-player game has a threshold effect means that it is a complex game. To see what makes it a complex game, i.e. the non-linear relationship between the payoff and the number of cooperators, we rewrite the collectivist payoffs as a polynomial function of \(k\) and observe that it involves powers of \(k\) greater than 1:

\[a_k = \frac{1}{6} B k^3 - \frac{1}{2} k^2 + \frac{1}{3} Bk - C \tag{2} \label{2}\]Because this is a complex game, an evolutionary inclusive fitness analysis requires Ohtsuki’s (2014) theory. Let’s assume that higher payoff from the game contributes to a greater number of offspring for that individual. Although “offspring” implies a genetic relationship, it could represent ideological offspring in a cultural evolution model. Then the change in the proportion of collectivists \(p\) can be derived

\[\Delta p \propto -p^5 \theta_{4 \rightarrow 4} B - p^4 (\theta_{4 \rightarrow 3} -\theta_{4 \rightarrow 4} )B - p^3 (\theta_{4 \rightarrow 2} -\theta_{4 \rightarrow 3} )B + p^2 (C-(\theta_{4 \rightarrow 1} -\theta_{4 \rightarrow 2} )B) + p (\theta_{4 \rightarrow 1}B -C) \tag{3} \label{3}\]where the \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) are higher-order relatedness indices, the probability that the strategies of \(l\) randomly sampled individuals from the group have \(m\) common ancestors.

The relatedness indices \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) in Eq. \ref{3} are the core innovation of Ohtsuki’s approach and the key to answering our question. They can be understood as \(n\)-player generalisations of the dyadic relatedness \(r\) that is traditionally used in inclusive fitness theory (i.e. \(r \equiv \theta_{2 \rightarrow 1}\)).

From Eq. \ref{3}, we can deduce that a population of individualists can be invaded by a small number of collectivists (enough to form at least one group) provided that \(\theta_{4 \rightarrow 1} > \frac{C}{B}\). In other words, collectivists can successfully invade a population of individualists if the cost-benefit ratio is less than the probability that the four individuals’ strategies are identical by descent.

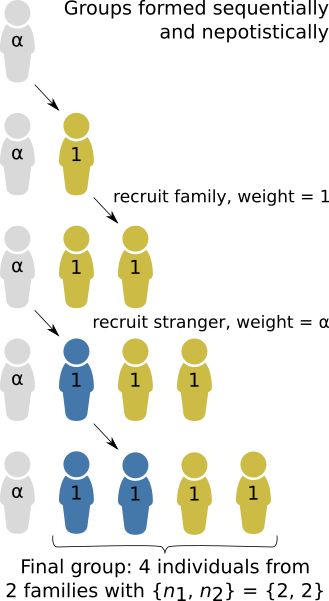

To obtain the \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\), we need some model of how the groups get formed. Here, I will assume simple nepotistic group-formation model (Fig. 2). Groups are formed sequentially by individuals recruiting their own family members. However, external forces may also cause a stranger to be recruited with weighting \(\alpha\). This parameter that allows us to control the degree of nepotism, with high \(\alpha\) indicating low nepotism. I’ll assume for simplicity’s sake that family members are clonal relatives. Then I can use Appendix C from Ohtsuki (2014) to calculate each relatedness index \(\theta_{l \rightarrow m}\) from the probabilities of each group composition.

Figure 2: An illustrative model of homophilic group formation by nepotism. Groups are formed by sequentially adding one individual at a time. At each stage, each group member has an equal chance (weight = 1) of choosing the next recruit, who will be their family member. However, there is also a chance that the next recruitment will be driven by external factors, and so the recruitment of a stranger is given weighting ‘alpha’.

The group composition will be an integer partition of the group size \(n\), i.e. \(\lbrace n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_\Phi \rbrace\), where \(n_i\) is the number of individuals belonging to family \(i\), and \(\Phi\) is the total number of families. Let \(\phi_j\) be the number of families with \(j\) group members. Then the probability of a particular group composition is

\[\mathbb{P}( \lbrace n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_\Phi \rbrace \mid \alpha ) = \frac{ n! \: \alpha^\Phi }{ \prod_{k=1}^n k^{\phi_k} \phi_k! (\alpha + k - 1) }. \tag{4} \label{4}\]Long-time readers of my blog will recognise the group formation process as analogous a Hoppe Urn and the resulting probability distribution as analogous to the species-abundance distribution of a random sample from the metacommunity resulting from Hubbell’s neutral theory.

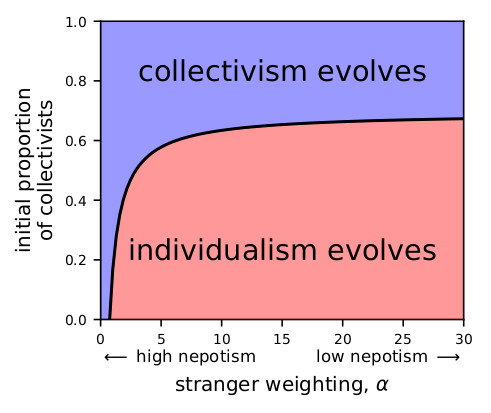

We find that the evolutionary trajectory of the population has two steady states: one where all individuals are collectivists and one where all are individualists. Which steady-state the population evolves towards depends on both the degree of nepotism and the initial proportion of collectivists in the population. In Fig. 3 (parameter values: \(B=3\), \(C=1\), \(n=4\)), if the degree of nepotism is very high (\(\alpha < 0.75\)), collectivism always evolves. Otherwise (\(\alpha > 0.75\)), collectivism will only prevail if the population is initialised with a large enough number of collectivists.

Figure 3: Regions in parameter space where the evolutionary dynamics will drive the population towards collectivism (blue) or individualism (red). The likelihood of collectivism decreases with decreasing nepotismand depends on the initial proportion of collectivists in the population.

Nepotism promotes cooperation because it promotes positive assortment, i.e., individualists and collectivists tend to segregate into different groups. When groups of only collectivists occur frequently enough, then the benefit of collectivism outweighs the risk of failure in a group with individualists. This model illustrates why homophily is generally expected to promote cooperation; however, in the real world, it is not so easy for cooperators to identify fellow cooperators and form groups with them.

References

Gross, J. and De Dreu, C. K. (2019) Individual solutions to shared problems create a modern tragedy of the commons. Science Advances, 5(4):eaau7296.

Ohtsuki, H. (2014) Evolutionary dynamics of n-player games played by relatives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 369(1642):20130359.